SNAKES SHARE THE same distinguishing characteristics of other reptiles. They have scales covering their body, which are comprised of keratin – the same material your fingernails are made of, giving them a dry, smooth feel.

Snakes are ectothermic (cold-blooded) and rely on the external environment to regulate their body temperature – this is why snakes and other reptiles bask in the sun. And although most species lay eggs, some snakes such as the red-bellied black snake give birth to live young.

Relying on sight, smell, and vibrations, smell is their strongest sense. Flicking out their tongue, they are able to taste particles in the air; these chemicals are then processed by the Jacobson’s organ and allow the snakes to visualise their surroundings. Some snakes, such as pythons also have heat sensing pits above their lips which allow them to see warm blooded creatures the same as an infrared camera would be able to.

Snakes through history

Snakes have evoked love and hatred among humans for thousands of years.

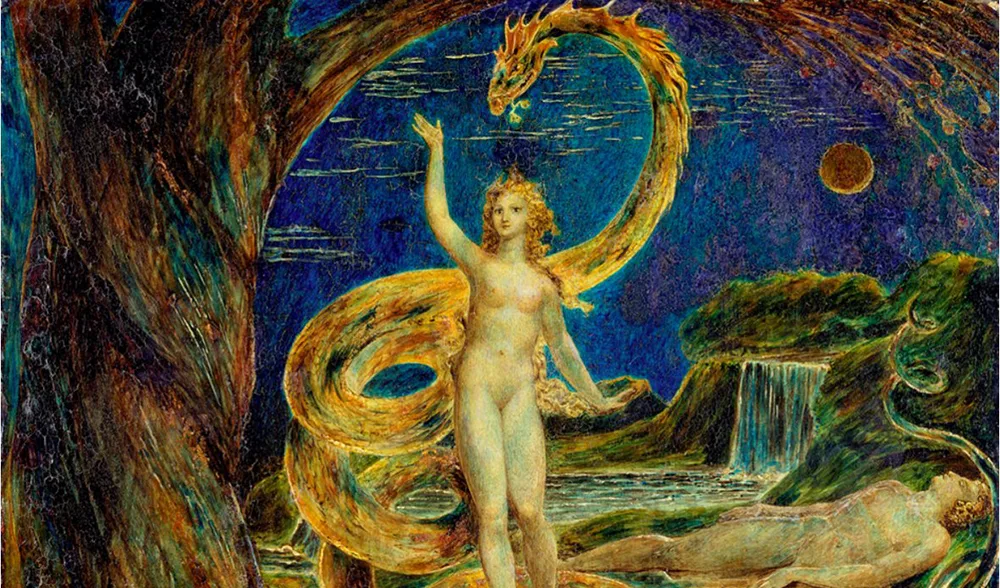

Representing sin in Christianity, other cultures and religions view snakes more highly. In ancient Egypt the Egyptian Cobra adorned the crown of the Pharaoh. In ancient Greece they could be found in many medical symbols, such as the Rod of Asclepius, which is still used today. Further east in India, Hindus celebrates Nag Panchami, a day when snakes are venerated for their power over the rains. In China, the snake holds a place on the Zodiac calendar. And in non-Eurasian cultures, snakes were welcomed in Peru and Mexico, where they were revered as mortal forms of the gods.

Eve Tempted By The Serpent, painting by William Blake. Snakes have held strong symbolism throughout history and are referenced throughout the Christian bible. (Image: Wikimedia Commons).

Long-lost limbs

Have you ever noticed how a goanna flicks out its tongue like a snake? Goannas are believed to be snakes closest limbed relative. In fact, one of the oldest snake fossils in existence, dating back 120 million years, Tetrapodophis amplectus (literally meaning, four-legged snake) shows a snake with distinct limbs.

While snakes today do not appear to have any limbs, some species still have remnants of their legged past. Pythons and boas, for example, still have tiny hind leg bones buried in muscles toward their tail-ends. While they obviously offer no benefit to the snakes today, they serve as an evolutionary puzzle piece to their past.

In July 2015, scientists described the first-known fossil of an approximately 120 million year old four-legged snake. (Image: Dave Martill/University of Portsmouth).

Fatal instinct

Australia is home to over 190 species of snake, 25 of which are toxic to humans and 20 of those are among the most venomous in the world.

Despite Australia harbouring many of the world’s most dangerous snake species, snakebite deaths are rare and only account for about two deaths a year. Statistically, you are more likely to be killed by a dog or a cow than a snake.

“Ninety per cent of snakebites in Australia are from people mucking around with them, trying to kill them or impress a girlfriend,” says Billy Collett, head of reptiles of the Australian Reptile Park, and one of the few people who makes a living milking snakes for the production of antivenom.

If immediate proper medical care is sought, bites are rarely fatal.

The eastern brown snake (Pseudonaja textilis) and its western counterpart (P. nuchalis) are responsible for most fatalities. Combined, they inhabit nearly every corner of the country.

Although they have small fangs, they can deliver large quantities of venom. Evolved to disable and digest prey, venom is modified saliva. It contains powerful enzymes that begin liquefying prey from the inside out. Nearly all Australian snakes have a neurotoxic type of venom; this type of venom causes the brain to lose its ability to communicate with other bodily organs. In addition, the venom contains potent toxins that interfere with blood clotting.

The eastern brown snake is Australia’s most deadly. (Image: Peter Woodward).

“Back away slowly”

It is recommended that if you see a snake, back away slowly. Most snakes are skittish and will do their best to avoid conflict if given the opportunity to escape. Avoid walking in the bush with open-toed shoes and wear pants. It is also advisable to carry a pressure bandage with you if going on a hike. Spring is usually the most active month for snakes, when males are actively seeking females to mate.

If you are bitten it is important to stay calm, don’t try and capture the snake, as doing so will likely result in repeated bites. Anti-venom is available for all venomous snake species in Australia.

“Doctors have become good at diagnosing by symptoms, and they can do a test from the bite site or the blood to determine the type of anti-venom you require,” says Collett.

Call 000 immediately and have someone apply a pressure bandage while you wait for emergency services.

Medicinal benefit

They say out of destruction comes beauty, and this is certainly the case with snake venom. While the raw form can wreak havoc on the human body, individual components derived from venom are offering hope in the treatment of numerous diseases.

Some examples include:

Cancer (various types): A protein called eristostatin, taken from the venom of the Asian sand viper, could be helpful in the fight against melanoma and other cancers. In the USA, an enzyme from copperhead (Agkistrodon contortrix) venom is under development to treat breast cancer.

Stroke: Components of Malaysian pit viper venom has shown potential for breaking blood clots and treating stroke victims.

Excessive bleeding: A blood-clotting protein in Taipan venom has been found to stop excessive bleeding during surgery or after major trauma.

Neurological diseases: Enzymes from cobra venom may be instrumental to finding cures for Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease.

Fast facts

Snakes are deaf, they have no external ears.

Snakes can visualise their surroundings using their tongue to pick up chemicals in the air.

Snakes are found on every continent except Antarctica.

Snakes have no eyelids.

Before shedding, a snake’s eyes will become cloudy/opaque

Endemic to Western Australia’s Pilbara region, the Anthill python (Antaresia perthensis) is the smallest python species in the world.

The yellow bellied sea snake (Pelamis platurus) is the most widely distributed snake in the world, found in tropical oceanic waters across the globe excluding the Atlantic.

Mother pythons will coil themselves around their eggs using their bodies to regulate the eggs temperature during incubation

There are no snakes native to New Zealand.

Most snakes are immune to their own venom.

Anti-venom is produced by injecting small amounts of venom into a horse and then extracting the antibodies.

The king cobra is the longest venomous snake in the world, and eats other snakes, including other king cobras.

The amethystine python (aka the scrub python) is by far the longest snake in Australia, it grows up to 6m. They inhabit the rainforest regions of far north Queensland.

WA’s anthill or pygmy python is the smallest python in the world. (Image: Wikimedia Commons).

What to do after a snake bite

Call 000

Keep the person who has been bitten as still as possible. If possible, lie the patient down to prevent walking or moving around.

Until help arrives, if the bite is on a limb, apply a pressure-immobilisation bandage but not so tight that it will cut off circulation.

If the bite is not on a limb, apply direct and firm pressure to the bite site with your hands (it is also important the patient is kept still).

Keep still and await the arrival of the ambulance for transport to the nearest hospital.

WORDS BY DEREK DUNLOP | A VERSION OF THIS STORY ORIGINALLY FEATURED ON AUSTRALIAN GEOGRAPHIC.

A video suggestion for you: Chris Klein and wife Laina are expecting their first child!