We are in 1963 and while London is swinging, it seems it’s not quite ready to embrace the sexual antics of the Duchess of Argyll.

Born in 1912, the vivacious, party-loving Margaret Campbell was the darling of Britain’s society set until a bitter and very public divorce battle with her second husband, Ian Douglas Campbell, 11th Duke of Argyll, one of Scotland’s most powerful noblemen and owner-occupier of the 90-room Inveraray Castle, ripped her reputation to shreds.

The acrimonious split was the culmination of years of legal wrangling as the tempestuous couple indulged in ever-increasing tit for tat skirmishes, suing and counter-suing each other.

But what was revealed and pored over in smutty detail in the final courtroom stoush shocked the nation.

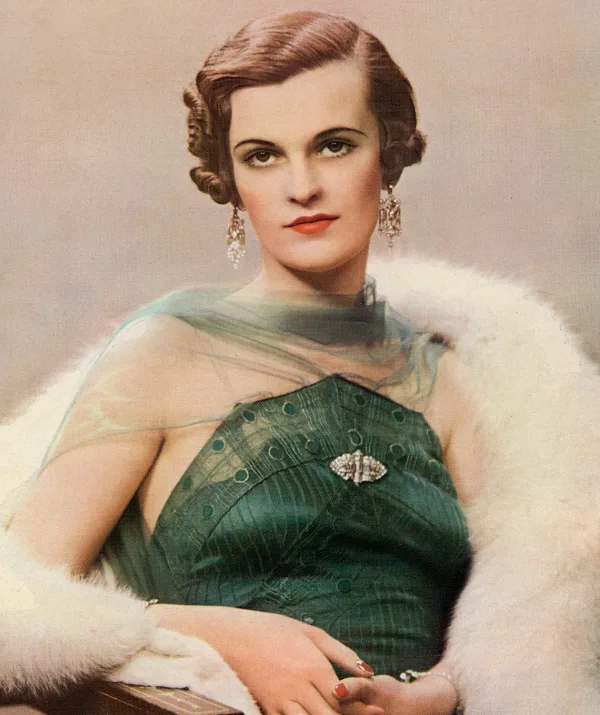

Margaret was incredibly popular and charming

(Photo: Shutterstock)This was the longest, costliest and most notorious divorce trial in British history, opening up the Duchess’s private diaries to painful public scrutiny and famously hinging on a set of pornographic polaroid photographs that the Duke had stolen from his wife’s private desk drawers and cupboards in her London townhouse while she was overseas.

In the arty images were the torsos of naked men with a woman, her face turned away from the camera, performing oral sex.

Though the features were unrecognisable, Margaret could be identified by her signature three-strand pearls.

When questioned, she claimed the man in question was the Duke, which prompted a medical examination to see if his naked attributes sized up!

The doctor declared this was not in fact the Duke, who in his divorce petition had listed the names of 88 lovers he claimed his wife had entertained throughout their marriage. He then named three suspects whom he suggested could be “the headless man” in the photo.

The case hit front page headlines day after day and neither the Duke nor the Duchess came out of it well. Their louche living was laid bare, the Duke’s addictions and brutality picked over; but it was Margaret’s reputation that was dragged through the mud.

The judgements of disapproving men displayed what, with 21st century eyes, feel like the deep-seated misogyny and sexism that propped up the framework of the decaying aristocracy Margaret had married into. I suspect we would see her in a different light today.

Certainly Margaret dared to take on the hypocrisy of her accusers and was punished for her audacity.

That she enjoyed the company of men and enjoyed sex wasn’t something she felt she had to hide. The physical and emotional cruelty she endured at the hands of her husband she also wasn’t going to brush under the Persian carpet – that and his brazen theft of her family money.

Margaret on her way to being presented to the royal family at Buckingham Palace in the early 1930s.

(Photo: Getty Images)Until this vile dressing down, Margaret, then 51, had been the beau monde’s glittering jewel of charisma at every event she graced.

But now she was depicted as a lying, scheming nymphomaniac or, to quote Judge Lord Wheatley’s excoriating 64,000-word judgement, “a highly-sexed woman who had ceased to be satisfied with normal relations and had started to indulge in what I can only describe as disgusting sexual activities to gratify a basic sexual appetite”.

The Duke was ultimately granted his divorce and Margaret lived until she was 80, doughty to the end, but this fascinating, if skittish Duchess never regained her standing among the ruling classes, and died penniless and ostracised by her own family.

So what really happened here?

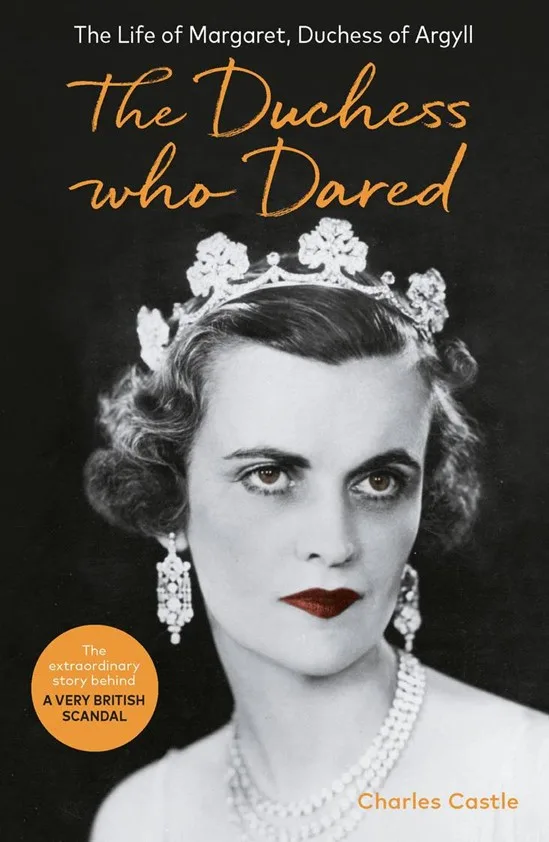

Margaret’s story is reassessed in a gripping new three-part TV drama – A Very British Scandal – and the re-release of Charles Castle’s 1994 biography The Duchess Who Dared, based on an extraordinary series of exclusive interviews with Margaret which took place in the mid-1970s but couldn’t be published at the time for legal reasons.

Charles Castle’s 1994 biography The Duchess Who Dared

(Photo: Swift Press)Margaret was an heiress in her own right, the daughter of a Scottish self-made man and raised in a world of incredible financial privilege and comfort.

“She was an enchantress,” writes Charles Castle, “considered one of the most beautiful women of her generation and one of the 10 best-dressed in the world. Charming, elegant and gregarious, she was sought after.”

British actor Claire Foy, who plays Margaret in the TV series, describes Margaret as “an ‘It Girl’ and a debutante … The year that Margaret was presented to court was the year it was all about fashion and romance. She came out when she was young – at 16. She just loved everything to do with society and being in amongst it. She was special.”

The fact that Margaret wasn’t born into the aristocracy and was raised in America didn’t hold her back, and though many felt she ached to be part of the blue-blooded beautiful people set, Claire is not so sure.

“Margaret was new money; her dad had worked really hard and she had the best of everything. But I don’t think she ever doubted in her life that she deserved everything; she was a social climber in a way but she wasn’t hungry for it.”

Margaret and her first husband, Charles Sweeny, on their wedding day in 1933.

(Photo: Getty Images)One thing was obvious, though: Margaret loved to go out, adored the company of men and they adored her.

Many of the male friends who were cited as her lovers were most likely gay. Homosexuality was illegal and for Margaret, these men made wonderful escorts on nights out on the town.

By the age of 19 she already had four engagements under her belt, including to the Prince Aly Khan.

She eventually married US socialite and businessman Charles Sweeny in 1933. They had two children but the relationship ran out of puff, cordially so, and she divorced in 1947.

Four years later she fell hard for the Duke of Argyll. By all accounts, including her own, she really was in love, but things started to go wrong very quickly. Ian Campbell was a damaged man, suffering PTSD from his time as a prisoner of war in the Second World War.

He was addicted to alcohol, gambling and possibly drugs and outrageously sponged from his wives’ family coffers – Margaret was his third spouse – to fund the running of his ancestral seat, Inveraray Castle, moving on when they realised what he was up to.

Margaret with the Duke of Argyll and their family in 1951;

(Photo: Getty Images)He was also unfaithful and though he could be charming, his behaviour was erratic and often cruel. Margaret was very much his latest victim.

“Ian is a Duke and that’s deeply attractive to her,” notes Claire. “In this period of time, Margaret has met every type of person in her circle. She loved entertaining; actors, politicians and collected people. In Ian, she meets someone who is different, who makes her laugh and who is arm candy. He’s very handsome and the ‘un-gettable man’. He is the one you want to be able to change; married twice before and she wants to succeed where two other women have failed. She falls in love with Inveraray Castle and sees it as so romantic. She was hopelessly romantic and sees the castle as a dream. But the dream goes terribly wrong.”

“He toyed with me as a cat plays with a mouse,” Margaret confided to Charles Castle, “and every time he sensed that I had come to the end of my tether, he would then choose to become his most agreeable self, ready to do anything to please me. He was such an attractive man, I was a mere pawn in his hands. Even my father, who was such a clever man, was putty in his hands.”

“They are toxic from the beginning,” explains Claire. “Margaret is very high-octane and his life is very much about alcohol and his addictions. She naively went into the relationship and didn’t want to find out anything else about him, but also vice versa.

“It’s fascinating in a way as I’ve never been in a drama where both of the people are so openly flawed. They don’t try and lessen their snobbery, their naivety or any of those things. They do love each other and it is, in its own way, a love story. Ten years after they divorced, Ian died. I would like to think there was some sort of romantic unfinished relationship.”

When it all falls apart, the vitriol on both sides is brutal but especially from the Duke, who sets out to destroy his wife in a very public way.

While biographer Charles Castle became increasingly aware of Margaret’s faults – she definitely lied, for instance, in court and out, and forged letters to the Duke questioning the legitimacy of his children from his first marriage as well as falsely accusing him of infidelity with her own stepmother – he did admire her strength of character.

“Something in her nature drove her on without fear to do precisely what she wanted, no matter the consequence,” he writes.

For Sarah Phelps, who wrote The Very British Scandal TV series, it is this part of Margaret’s personality that is most fascinating to today’s audience.

“It’s a story about a woman who refused to be slut-shamed, who refused to go quietly and refused to do as she was told,” she says. “She set fire to the expectation of her class, gender and her sex rather than go quietly. She put the private lives of the wealthy, the landed and the titled all over the front pages, not the untouchable great and good but bare, forked animals. Judge Wheatley’s three-hour-long indictment of Margaret’s character, her sexual morals, destroyed her … but I think she’s heroic.”

In light of current #MeToo battles, it is tempting to see Margaret as a pioneer, and Claire thinks the resurgence of interest in her story is because it does have a new focus.

“I hope that this drama allows a woman who was judged, ridiculed, belittled, manipulated and taken advantage of by the legal system, to at least have that shown. I think that the law doesn’t particularly treat women very well at all and this is just one example of how the odds were not stacked in her favour. She was an interesting woman and the more stories about interesting women, the better.”

“Something in her nature drove her on without fear to do precisely what she wanted, no matter the consequences.”

(Image: Getty)For Sarah, Margaret is a woman to be admired.

“She was honourable. Even before the nature of the photographs were made evident, Margaret was accused of having more than 80 lovers. She could have defended herself; some were single friends in extra-marital affairs and others, if she’d been honest about them, would have been sent to prison for being gay.

“But Margaret never betrayed her friends. That’s honour. She was spoiled, troubled, complex, demanding, infuriating, beautiful, stylish, silly, generous, vain, bloody-minded, very funny and brave. I love her for all of it. She’s an icon.”

A Very British Scandal streams on Amazon Prime Video on April 22. The Duchess Who Dared by Charles Castle, Swift Press, is on sale now.

You can read this story and many others in the April issue of The Australian Women’s Weekly – on sale now

.jpg?resize=380%2C285)