Jake Blair, 25, from Mount Gambier, SA, shares his shocking true life story;

I leaned forward and blew out the candles on my ninth birthday cake.

“Make a wish,” encouraged my father, Garry.

Other boys my age wanted a new bike or trip to Disneyland.

But I had just one wish: to know why my mum had left me.

It was a mystery that had haunted me for as long as I could remember.

“She’s gone, mate,” Dad replied vaguely whenever I’d raised the subject. “She loved you very much.”

Her absence had obviously affected him a lot, too, as he got particularly misty-eyed around my birthday.

Part of me wondered if I’d been too unlovable for her.

Why else would she just walk out and never come back again?

Dad and I moved around a lot, as he drifted from one relationship to another, palming me off on friends while he numbed himself with booze and drugs.

When I was five, we’d moved in with Dad’s new partner, Bec, a mum with four kids.

But even in my new family I still felt lost without a mother.

“Why doesn’t your mum ever walk you to school?” asked one of my classmates.

Me with Dad – he could never talk about what happened.

My heart pounded as I scrambled for an answer.

I was so shaken that the school called Dad to come and collect me.

Later, he took me for a drive to Casterton, the small Victorian town where he and Mum had grown up.

Pulling up at the local cemetery, I followed him to the rows of headstones.

“That’s your mum’s grave,” Dad mumbled, pointing to a slab of stone inscribed with the name Deborah Anne Fream.

She’s dead, I gulped, realising that my dreams of her magically returning one day would never happen.

I pressed Dad for more, but he couldn’t even explain how she died without choking up.

Years passed and I thought of Mum all the time.

One day at school a group of kids crowded around me.

“We saw you on TV,” one of them said. “Your dad was talking about your mum.”

“What about her?” I asked, confused.

The teacher quickly interrupted and ushered them away, but the scene played on my mind all day.

That night, I mentioned what they’d said to Dad, who shot Bec a look and handed me some old magazines.

“Read these,” he said, anxiously downing a beer.

Turning the yellowed pages, I started to shake as I saw the headline and photos.

From reading the article, I learnt that I’d been asleep in my cot the night my mum, Debbie, 24, ducked out of our house to get some milk and never returned.

Mum went out for milk and never returned.

The story said a manhunt was already underway to catch the killer of Frankston TAFE student, Elizabeth Stevens, 17, who had been viciously stabbed and choked to death one month earlier.

An hour before Mum headed to the shops, the killer had attacked another woman, but she’d managed to escape and he’d fled into the darkness.

When he spotted my mother rushing into the shops, leaving her car unlocked, he slipped into the back seat and waited for his next victim.

As soon as she returned to her car, he pounced, forcing her at knife-point to drive to an isolated paddock at Carrum Downs where he repeatedly stabbed and strangled her to death.

The discovery of my mother’s body a few days later revealed the two murders were connected and that a serial killer was on the loose.

While extra police patrolled the streets, local women were warned not to venture out alone after dark. Frankston, which was usually bustling, became a ghost town.

Amidst the grief, my shattered dad made a televised appeal asking people to help catch the monster, dubbed the Frankston Serial Killer, who had robbed his 12-day-old son of his mother.

I gasped as I saw a photo of me, cradled in Mum’s arms.

But she wasn’t his last victim. Days later, the body of local student Natalie Russell, 18, was found on a nearby reserve bearing injuries similar to my mother’s.

My mum, holding me as a newborn.

The net tightened when a postal worker told police she’d observed a man watching Natalie through binoculars from a rusty yellow Toyota shortly before the murder.

The car belonged to local misfit, Paul Charles Denyer, 21, who was arrested and later admitted to all three murders.

“I hate women,” Denyer explained.

“Why those women?” police pressed.

“Just had the feeling,” Denyer shrugged.

It was like something out of a horror story.

Part of me didn’t want to keep reading, but I couldn’t stop.

I was relieved to read that Paul Denyer was jailed for life for the vicious killing spree.

The courts gave a minimum sentence of 30 years for the crimes.

The Victorian Supreme Court heard Paul had been fantasising about killing women for three years, developing a taste for blood after slashing the throats of his neighbour’s cats and leaving death threats on her walls in their blood.

My stomach sank realising why my birthday, just 12 days before the anniversary of Mum’s murder, was always so painful for poor Dad.

It was a lot to take in for an 11-year-old. It broke my heart to know that the couple of photos we had of Mum were as close as I’d ever get to her.

Other family and friends had their own stories and memories of her.

But I had nothing.

Mum and me – these photos are so precious to me.

I tried my best to get on with life, but Dad and I both struggled emotionally.

One day I bought a new motorbike and the two of us went out riding at a local quarry with family.

I watched Dad ride up the side of the quarry but when he got to the top, I lost sight of where he’d gone, and went down to see what had happened.

I found him unconscious, trapped underneath the motorbike, with his leg wrapped around it.

We all tried to get help but there was no phone reception, so I rode back to the main road and flagged down a car.

At the hospital, doctors took us aside. “Your dad is paralysed from the neck down and will never walk again,” they warned.

In the three years that followed Dad slowly lost all hope, finally passing away aged 44.

Staring at his lifeless body, I realised this was the only time I’d ever seen him free of pain.

After Dad’s death I tried to numb my own pain with drugs, and even ended up homeless for a while.

During my darkest days, I fantasised about taking revenge on the Frankston Serial Killer.

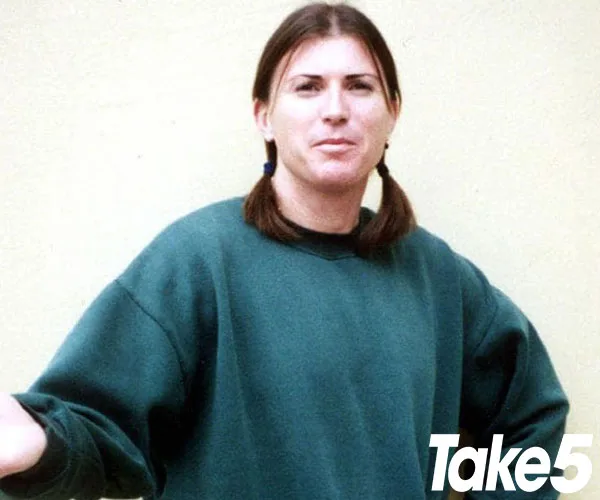

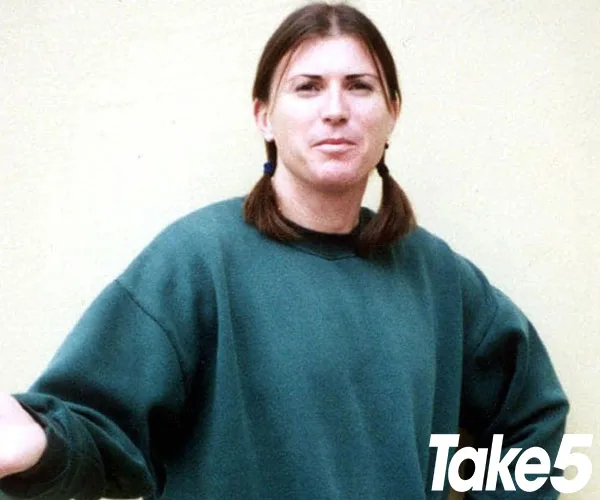

Paul Denyer outside court.

I’ve heard the stories about Denyer’s reinvention behind bars as Paula Denyer, a transgender woman who blames the crimes on a sexual identity crisis and wants the taxpayers to pay for surgery to become a woman.

But Paul – or Paula – remains a dangerous killer, who belongs behind bars for such evil crimes.

Five years from now, when Denyer applies for parole, I’ll be at the hearing to remind the authorities about the life sentence given to a 12-day-old baby and his dear mother.

WATCH: One-punch killer jailed: