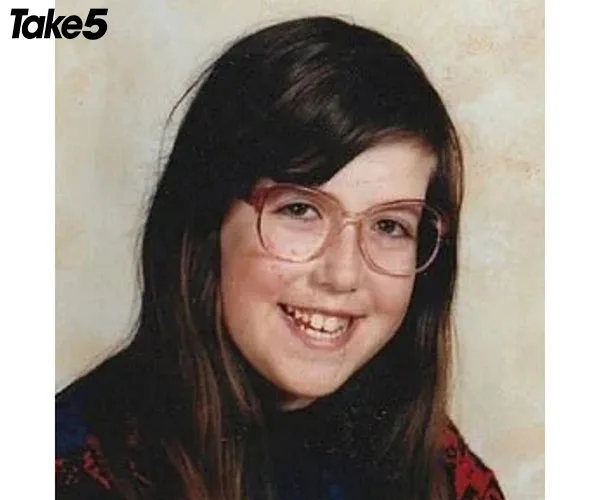

Zena Cooper, 42, shares her surprising true life story;

The familiar scent of cigarette smoke and cheap perfume wafted through the school playground.

I sniffed as I walked, following my nose until I’d reached my nan, Betty, who put out her ciggie and wrapped me in her arms.

“How was school, love?” she asked, squeezing my hand.

I looked at her and smiled, even though all I could see was a blurry outline and a few colours, all fading into one.

We walked home and I used my memory to make my way. When we came to busy roads, I let Nan’s hand guide me.

The route was so familiar, it didn’t matter that I couldn’t see – I knew which way to walk.

My eyesight had been all but non-existent my whole life.

When I was four years old, I was diagnosed with Marfan syndrome, a genetic disorder that affects the body’s connective tissue.

It can lead to a weakened heart, lungs, bones and joints, but for me it mainly damaged my sight.

Being so young, I had no idea what the docs were talking about.

“Everything will be fine,” my mum, Jennifer, soothed.

Thankfully, once I was diagnosed and received prescription glasses, the appointments became less frequent.

Mum and my dad, Peter, thought the glasses helped me, but the truth was I couldn’t see whether I wore them or not.

I never admitted that my glasses didn’t help me at all.

(Image exclusive to Take 5)I didn’t tell anyone because, at first, I didn’t realise being blind was unusual. I thought everyone was looking at the same big blur that I was.

I still knew what Mum cooked for dinner based off the smell and I could dress myself, I just had to feel for the seams and zippers.

It wasn’t until I was at school that I realised I was different.

The chalkboard in class looked like a fuzzy mess covered in white squiggles.

When a classmate read off the board, my stomach sank. Clearly it wasn’t just my glasses that made me different – there was a whole world I couldn’t see!

So I figured out a coping mechanism and adjusted. My friends were good students and took detailed notes.

“The projector screen was too glary with my glasses,” I said to my friend after class. “Could I copy your notes?”

She was always happy to help.

I still used my memory to get around. If someone unexpectedly left a bag on the floor or a chair out, I’d bump into it.

I was normally covered in bruises, but I brushed it off as clumsiness.

I knew I was living a lie, but I didn’t know how to stop. By the time I realised no-one else was blind, it felt too late to come clean.

How do you walk up to someone you’ve known for years and say: “By the way, I’m blind”? I was an imposter in a world of vision and I didn’t want people to know how different I really was.

Me with Mum. My parents never guessed my secret.

(Image exclusive to Take 5)By adulthood, lying about my vision was second nature.

At 19, I got married and fell pregnant with my daughter, Rasheena. Just one year later, I had another daughter, Korisha.

I was nervous about raising two babies under the age of two, but I took to it naturally. Because I couldn’t see, my sense of smell was incredibly strong, so I always sniffed out dirty nappies.

Even when my bubs fell sick with a cold, I could smell the illness. Their skin gave off a sour odour that only I noticed.

They grew into incredibly well-behaved girls. In public they always stuck by my side, so I could feel where they were. I’d never told them I couldn’t see – it was like they intuitively knew to stay close to me.

After a few years, my husband and I split. Then, I fell in love again. When Korisha was four I had a son, Jaidan, followed by another son, Zaidley, one year later.

Before long, I became a single mum to my four kids and life was more hectic than ever. But with my parents’ support I pulled through.

I worked as a school counsellor, recognising the individual students by their voices.

With the change in routine, I struggled to remember where stairs and doorways were.

I became clumsier than ever and suffered eight knee dislocations in two years.

I was at my wits’ end when one of my students came into my office to change the time of his appointment.

I’d only recently met him and his voice was so similar to another student’s that I got the two boys confused.

Thankfully, no confidential information was given to the wrong person, but I’d come so close to disaster.

As a counsellor, I dealt with the most sensitive topics. I couldn’t risk another mix-up.

It was time to accept that I had to come clean and I needed a guide dog to help me get around.

Me and my kids: Korisha, Zaidley, Rasheena and Jaidan.

(Image exclusive to Take 5)That night, I told my kids the truth.

“I’m blind,” I said nervously. “I’ve never been able to see you. I recognise you from your smell and your voice.”

They were shocked but supportive. Only my youngest, Zaidley, then 13, was nervous.

“What if people are mean to you?” he asked.

I pulled him in for a hug.

“I don’t care what people think anymore,” I beamed.

My friends and colleagues were so understanding, but telling my parents was the hardest thing I’d ever had to do.

“Why didn’t you tell us?” Mum asked tearfully. “We would’ve helped you!”

I choked back tears as I explained that that was exactly what I wanted to avoid.

I didn’t want anyone treating me differently just because I couldn’t see.

Munch assists me everyday and life is so much easier now.

(Image exclusive to Take 5)Once everyone knew the truth, it was like a weight had been lifted.

Finally, I was free from my double life.

Now, I have a guide dog called Munch. He’s made life so much easier.

I decided to write a book about my experiences. I want the world to know that even though I see things differently, the world is just as beautiful to me as it is to everyone else.

For 38 years I was living in the dark. Now, I’ve shined a light on what the world is like for me and I won’t ever hide away again.

What You See When You Can’t See, by Zena Cooper. Published by Hay House, RRP $20.93

(Image: Supplied)