Gregory Smith, 65, Coffs Harbour, NSW shares his story:

I sat on the beach and looked at the lush green mountains in the distance.

“You’d like it up there, mate,” a stranger had told me earlier. So in a moment of spontaneity, I began walking.

I didn’t know how far it was or how long it would take, but I was determined.

Trudging along the road, I hit the small town of Mullumbimby, NSW, after a few hours, but this wasn’t my final destination.

Wearing jeans, a T-shirt, army boots and an akubra hat, I kept walking. In my pack, I had a full length Driza-Bone raincoat, some tobacco, and a few essentials.

I eventually arrived in the forest, and loved it so much I decided to make it my home.

When I’m ready, I’ll go back to society, I thought, setting up my camp.

It wasn’t where I imagined I’d end up in my 30s.

Growing up in Tamworth, violence was common in my house. I suffered abuse at the hands of my dad, Bruce, and my mum, Beryl, made excuses for him.

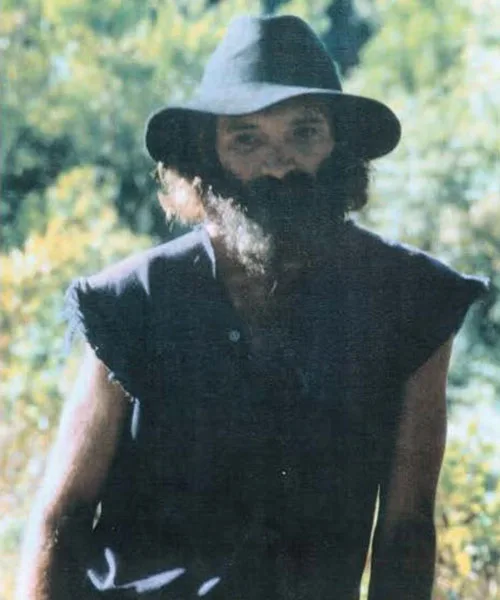

Me when I was living in the bush.

(Image: Supplied)A few years later, when I was 10, my four sisters and I were sent to an orphanage and didn’t return for 16 months.

At just 14, I’d developed a habit of running away and the older I got, the further I ran.

But after getting into trouble with the police too many times, I was locked in juvenile detention. There, a psychiatrist described my personality as sociopathic.

As I grew up, I numbed my pain with drugs and alcohol.

When my first wife Julie left me, I became homeless for the first time.

From the harsh footpaths of Kings Cross in Sydney, all the way to Cairns, I searched for a better life.

I’ve slept on urine-spattered tiles of public toilets, industrial rubbish bins, railway platforms and even verandahs of unsuspecting Aussies.

In the open, I was a target for random beatings, and the elements would work against me, be it a cold snap or rain. I was constantly tired and hungry, and society thought the worst of me.

My mum and dad.

(Image: Supplied)Years later, I returned to Tamworth and met Nicola. I got work in a car yard and she’d happily make dinner most nights.

“What’s cookin’ good lookin’?” I’d ask when I got home.

“Rissoles, darl,” she’d say.

Life seemed perfect.

But nothing could have prepared me for the gratitude I felt when she gave birth to our daughter Katie.

“She’s beautiful,” I beamed, holding our newborn. “Life’s finally turning around.”

We returned home but a week later, Nicola left with Katie. I didn’t know what had happened. I tried to get Katie back, but couldn’t. I’d lost both my girls.

Heartbroken, I returned to the land of the lost.

I thought about Katie often, but the pain of missing her was too much.

Years rolled by in a blur of substance abuse until I got to Byron Bay and decided to walk into the forest. I’d hit rock bottom.

The first night was one of the wettest I’d ever known. With just the tree canopy as shelter, I was soaked by morning.

But that didn’t bother me. Instead, I was struck by the sun glittering off the wet bark.

I’ve come to terms with my past.

(Image: Michelle Ransom-Hughes)For once, nobody was chasing me, no-one was telling me to move on and I wasn’t being kicked in the guts. I felt like I belonged to the bush.

I foraged for food like bats, slugs and bugs, and lit camp fires. My hair grew wild and my clothes were tattered. Occasionally, I traded with locals in town. Some thought I was crazy, others said I was Jesus.

One night, I lay in my camp as my stomach grumbled and felt something slither over my chest. I heard a soft hiss. My eyes grew wide. A bloody snake! I kept still. A bite from a venomous one would be an instant death sentence.

When it slipped off me, I realised it was a huge but harmless diamond python.

Excellent, I thought.

I found my pocket knife and killed it. It’d been days since I’d last eaten.

“Sorry I had to kill you, mate, but I’m grateful your flesh will sustain me,” I said to the python. “I’ll never forget it.”

I could also use the scaly skin in a trade for supplies.

Life went on like this. I endured sickness, injury and malnourishment while coming to terms with the emotional pain of my past.

Sometimes, I’d let a relative know I was still alive, but communication with the outside world was minimal.

I’d developed a philosophy that I’d no longer hurt anyone. Living alone in the bush was the best way to do it.

My beautiful daughter Katie.

(Image: Supplied)Eventually, I started talking to imaginary beings that felt very real to me.

One was with a group of aliens that said my staying in the bush was wrong.

“By keeping away, you’re hurting the people you’re trying to protect,” they said.

I was so shocked by the notion I decided to pack up and move on. “I’ll give society one more chance,” I agreed.

Arriving in town after 10 years in the forest, I sat on a park bench with my wine, bourbon, and all I owned.

Suddenly, I had an epiphany – I was my own worst enemy, and the person I’d been avoiding was myself.

Step by step, I turned my life around. I got an education, and eventually went to uni.

I studied people like me who’d endured trauma in violent homes, even getting my PhD.

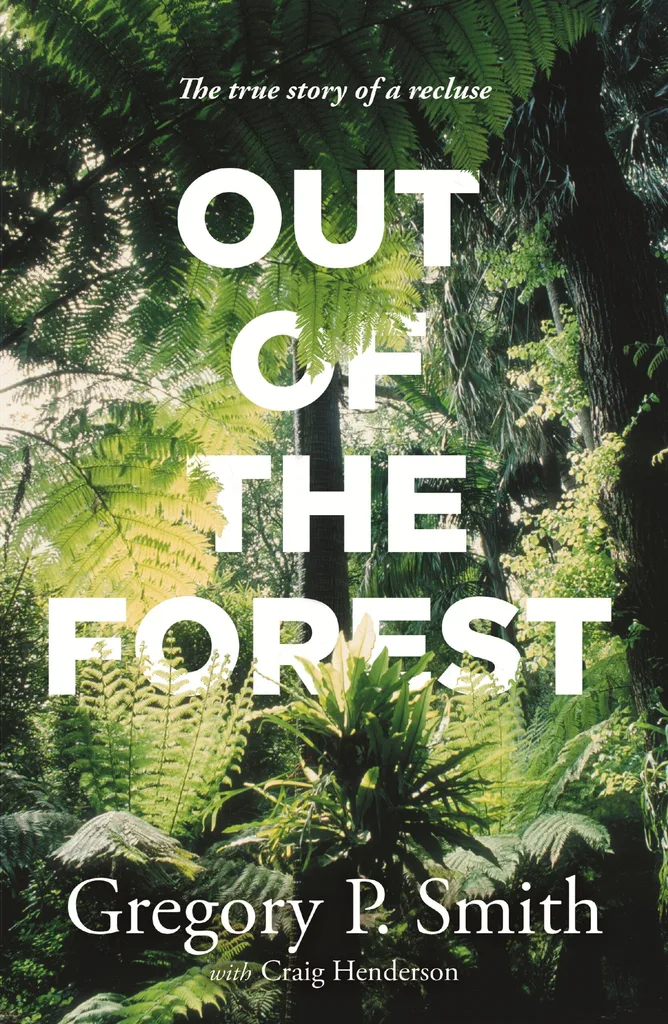

Gregory’s book Out of the Forest is available at good bookstores.

(Image: Supplied)Eventually, I decided to share my story.

With the help of ghostwriter Craig Henderson, we turned my experiences into a book, Out of the Forest.

Now, my daughter Katie, 34, and I are closer than ever.

I never imagined when I entered the forest for a life of solitude, things would turn out how they did, but those years alone genuinely helped me come to terms with my past, and my future is better because of it.

Gregory’s book Out of the Forest is available at good bookstores.