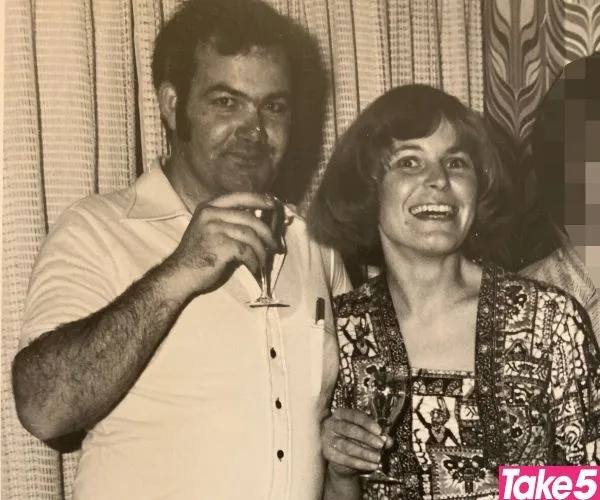

Grant Dansie, 38, Adelaide, SA, shares his tragic story;

My dad, Peter, clenched his fists in frustration as the traffic slowed to a halt.

Here he goes, I thought, bracing myself for his tirade of rage.

I was only seven, but I knew anything could set off my father.

Sure enough, Dad jumped out and threw bollards and signs around in a fit.

At home, my mum, Helen, tried to shelter me from his outbursts.

“Grant, come help me in the garden,” she’d say to me.

My parents were polar opposites.

Dad, a statistician with the Australian Bureau of Statistics, often threw temper tantrums, but my mother, a hospital microbiologist, was warm and loving.

We lived in the Adelaide foothills and had an Angora goat farm nearby.

When I was a teenager, some Jack Russells that belonged to local radio host Jeremy Cordeaux got in and killed some of the goats – and it wasn’t the first time they’d been in the paddock.

“I’ll teach them!” Dad thundered.

He ended up slitting the dogs’ throats.

“I would’ve shot them if I’d had a gun,” he said.

The awful incident attracted so much misleading media coverage that our family received death threats.

I knew anything could set off my father.

(Image exclusive to Take 5)Due to the stress, Mum suffered a stroke soon after, leaving her with little short-term memory and only able to speak in short sentences.

Thankfully, she had her pension and the support of family and friends – especially our kind neighbour, Ginny.

Dad and I bathed Mum, helped her to the toilet, fed and dressed her.

But Dad was reluctant to do more than the basics. He kept shouting at Mum, too.

When I got a high school exchange scholarship to study in Denmark for a year, I felt conflicted.

“Your mum would want you to go,” Ginny told me, vowing to keep an eye on her. I nodded.

Honestly, I needed an escape.

After uni, I settled in Norway, but I often returned to Adelaide to see Mum, who got around in a wheelchair.

One time when I came to visit, Dad simply refused to let me in the house. I didn’t know what to do.

Mum also fell over often because Dad hadn’t put in any rails and ramps.

I didn’t want to leave her with him, but I’d built a life overseas and knew she’d want me to live it.

Mum adored her grandson Max.

(Image exclusive to Take 5)So, with Ginny’s guidance, I fought to improve Mum’s care through the official channels, like the Public Trustee.

The process went on for years.

Dad would make promises about Mum’s finances or care, but never kept them and didn’t face any consequences. It was outrageous.

He’d even used $5000 of Mum’s money to buy a tractor.

When I was finally allowed to visit Mum, I noticed she smelled.

Her clothes were unwashed and her hair was matted. Dad clearly wasn’t looking after her properly.

Years passed before Mum was temporarily admitted to a nursing home, which brought me some relief.

When my partner and I had a little boy, Max, we went to visit her.

“Here’s your grandson,” I said, placing him in her arms.

“Hello,” she said, delighted.

Dad fought to get Mum back home, so he could control her finances and care, but his plan didn’t work out and she stayed at the nursing home.

By then, I mostly communicated with Dad through the authorities and lawyers.

When I tried to talk to him about Mum’s care, he’d either get angry or stay quiet.

Two years on, the public advocate was declared Mum’s joint guardian, which meant authorities had a shared say in her care and finances.

It was a win, but then I filed for a review of Dad’s role as guardian altogether.

If we won, he’d lose all control over Mum.

Peter Dansie.

(Image exclusive to Take 5)Shortly after, I was back in Norway when Ginny called.

“Your mother has passed away,” she said softly.

I was devastated. Poor Mum had been through so much…

At first, I thought it was another stroke. But, bizarrely, Mum, 67, had drowned in a pond in the Adelaide Parklands’ Veale Gardens.

Mum was wheelchair-bound and only capable of taking a few steps with help, and yet she’d drowned. How?

Was it an accident? Was it murder? I kept wondering, as I flew back to Australia.

Dad was a horrible person, but I’d never thought him capable of killing Mum. Was he? I thought.

Visiting the pond, I knew for sure that Mum had been murdered. She couldn’t have fallen in.

Even if she had, Dad could’ve saved her. The water was only about 110cm deep.

Apparently, he’d called triple-0 and “tried to help”.

In reality, it appeared he’d held her head under the water.

There was also no reason for him to take Mum to the pond at all.

Reaching it meant leaving the concrete path and pushing Mum’s wheelchair across uneven grass.

Dad was 70, unfit and overweight. He wouldn’t bother just for Mum’s benefit.

I was too sickened by it all to even feel anger towards Dad.

I just wanted justice for Mum.

The pond where Mum drowned.

(Image exclusive to Take 5)Next morning, two detectives showed up.

“Will you wear a wire to record your dad and testify against him?” one asked.

“Yes,” I said adamantly. I wanted Dad to pay for what he’d done to my mum.

I visited his house wearing the wire. He seemed totally emotionless about the loss of his wife of 44 years.

“[The water] was so deep, I couldn’t help her,” he said pathetically.

He refused to say any more. But a few months later, he was charged with Mum’s murder.

I was so relieved.

Dad pleaded not guilty, but the evidence was overwhelming.

It was revealed the triple-0 operator had told him 12 times to lift Mum’s head out of the water, but he kept making excuses, saying he had bad knees and diabetes.

He’d also taken his watch off and left it in the car, and before supposedly trying to “rescue” Mum, he placed his phone and wallet under a tree.

Detectives found messages between Dad and two women in China, who he was trying to meet for sex. He’d already packed his luggage with lingerie, condoms and Viagra.

Mum’s wheelchair in the park.

(Image exclusive to Take 5)When the judge found my dad, Peter Dansie, guilty, he was totally expressionless.

He was sentenced to life in jail, with a non-parole period of 25 years.Mum was disabled and a victim of her controlling husband.

She didn’t fall through a crack in the system – it was a gaping hole.

Despite all my efforts, the authorities did little to protect her.

Mum didn’t need to die, but because the system failed her, she was taken from me by my own merciless father.