Growing up, Bobby* was a quiet and reserved child. His mother Anne sensed he was a bit different from his elder brothers and encouraged him to purse his artistic interests. Yet as he grew older, he seemed increasingly uncomfortable in his own skin – as if he was holding part of himself back. His mum put it down to the awkwardness of adolescence.

Maybe he was figuring out his sexuality: it had crossed her mind that Bobby might be gay, although there hadn’t been any romantic interests that she was aware of. With a mop of sandy hair, freckles and a shy smile, he was popular among his peers at his local church youth group.

It was here that he seemed to have found his calling, putting up his hand to volunteer with the church’s outreach services and as a youth leader. The kids loved him: he always gave them his full attention and made them feel special. At summer camp, Bobby was a Pied Piper with a swarm of adoring children in his wake.

Although he hadn’t found a career, drifting between daytime jobs in customer service and retail, Anne was relieved he appeared to be finding his way in life. Until the day she got a phone call that would bring her regular suburban life to a sickening halt.

Bobby had been charged with sexually abusing a seven-year-old girl – and police suspected there were others.

Retching and shaking, Anne dropped to the floor. Her mind raced through a lifetime of memories of her youngest son, desperately looking for clues or signs that he had the capacity to betray a child’s innocence in such a heinous way. How had she failed him? What went wrong? How had it come to this?

Paedophilia, a word of Greek origin meaning “child love”, is a disorder defined by a persistent and dominant sexual attraction to pre-pubescent children. It affects about 1 to 2 per cent of the male population, plus a much smaller fraction of women.

There has been much debate over its cause, with theories ranging from psychological problems and pornography to celibacy and past sexual abuse. Yet science increasingly points to it being part of our biology – in other words, some people argue they are simply born that way.

Some clues have emerged to suggest it is innate: paedophiles tend to be shorter, for example, have a lower IQ and are three times more likely to be left-handed. MRI scans show they also have less connective tissue in the brain, with some scientists speculating that areas which govern their sexual and nurturing responses could be cross-wired.

This doesn’t, of course, mean we need to be wary of all people with these physical traits – it just indicates paedophilia could be rooted in our genetic blueprint before birth.

As part of its investigation, The Weekly tracked down and spoke to several men who identified as paedophiles. Nicholas, a married father-of-four, admits to being attracted to boys aged 12 to 14, but says he’s never acted on his urges.

“No-one chooses to be sexually attracted to children,” he says. “And those of us who are unlucky enough to be sexually attracted to children can’t [make it go away]. But many of us can and do successfully resist our attraction.”

Like Nicholas, who is part of an online support network, many paedophiles do not surrender to their impulses and abuse children. Conversely, not all child molesters are paedophiles. Some are opportunistic predators or sociopaths, who will target victims perceived to be easy prey. Aside from children, this could include disabled, drunk or elderly people.

In the past couple of months, a wave of high-profile cases of child sex abuse have left many of us horrified.

These cases are only the tip of the iceberg, as many victims don’t report sexual abuse or pursue their case through court because of shame and fear. A chilling disclosure by police that goes some way to illustrate the unknown quantity of child sex abuse in the community came following the abduction of Daniel Morcombe from a bus stop on the Sunshine Coast. Investigating police have since revealed there were at least 30 known child sex offenders in the vicinity on the day Daniel disappeared.

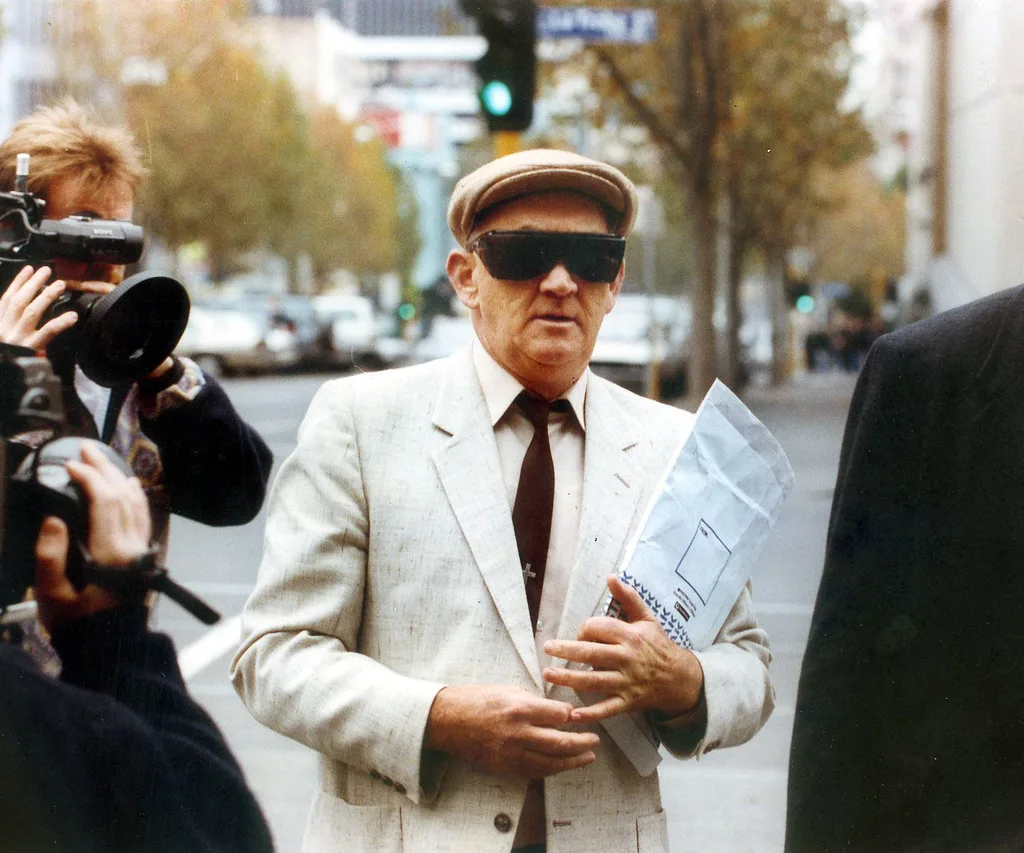

Gerald Ridsdale.

So can paedophiles ever be cured? The short answer is no – there has never been a proven case of someone who is attracted to children being converted into someone who is only attracted to adults. It’s more like a sexual orientation, but it can be controlled.

Nicholas, who admits his attraction to boys is far more powerful than any physical desire he’s ever felt towards his wife, compares it to diabetes. “It’s a serious chronic condition,” he says, “but a manageable one.”

He has kept his urges secret all his life, apart from confiding in a counsellor, and even today his family, including his wife, has no idea.

“I think I have a strong moral compass,” he says. “I realise that lots of kids have been hurt as a result of being sexually molested and I refuse to do anything that would hurt a child. In terms of strategies, I avoid being alone with kids that I find attractive. I’m sure nothing would happen, but I think it’s a prudent precaution.”

Nicholas knows what it’s like to experience sexual abuse as a child. At 12, he was molested by a camp counsellor.

“I’ve always suspected that this might have played a role,” he says of his paedophilia, although he accepts this isn’t the prevailing view.

Around half of child sex offenders have been found to have been abused themselves as children – yet experts don’t believe suffering abuse turns you into a paedophile. The vast majority of victims, after all, don’t grow up to become abusers, though experiencing abuse could increase your risk of breaking the law generally later in life.

“It could be that biology causes paedophilia, but that environment makes a person more likely to act on that sexual interest and molest a child,” explains James Cantor, a psychologist and sexual behaviour scientist at the University of Toronto in Canada, whose research on the biological indicators of paedophilia has challenged long-held beliefs.

Chemical castration is often pitched as a solution to paedophilia. This usually involves a doctor injecting testosterone-blocking drugs to dampen or eliminate sex drive. There are, however, problems with this option. It also prevents a paedophile from engaging in a healthy adult relationship, which in turn lowers the risk of them abusing a child and stops them managing the reality of their sexual attraction. And if they stop taking their medication, their impulses will return.

John, 76, an educated professional who spent a decade in jail after being convicted of serial assaults on young girls in NSW, takes the drug Androcur as part of a supervision order.

“It has side-effects,” he says. “I grew breasts. I even had to have a mammogram.”

He says the drug does diminish his libido, but he now has an adult girlfriend and hopes to wean himself off the drug when his supervision orders are lifted.

The question of what should be done with child sex offenders in Australia is fraught and for good reason. It centres around the protection our most vulnerable citizens – our children. Imagine your daughter, your grandson or a child you know being molested and it evokes a visceral response. We want nothing more than to protect them.

Turn your mind to the child molester and chances are you want them far away, locked up and closely monitored. It’s this response that has led to strict new laws being introduced in most states and territories over the past 11 years, allowing sex offenders to be detained and supervised even after they’ve served jail sentences. These men wear GPS ankle bracelets that allow corrective services staff to monitor their movement 24/7 via electronic surveillance. They must abide by rules, such as not going within 500m of a school, getting home by curfew, submitting advance schedules of their daily activities and taking medication. Perhaps most controversially, some live together in housing for high-risk offenders.

“[The supervision orders] curtail you,” says John, who wears an ankle bracelet and lives alongside other sex offenders. “You can’t live a normal life. It tends to make you worse because you try to figure out how to get round them.”

John, who was raped by his uncle from the age of five, believes there are sex offenders who are beyond redemption and should live under restrictions, but claims the law is being stretched to cover ex-prisoners who aren’t a real threat.

He says when he questioned his own status rising from low-risk to high-risk after satisfactorily completing a rehabilitation program in jail, a psychiatrist told him, “It’s very simple. What if you go out [of jail] and do something wrong, and we’d said you were low-risk? We will get our arses kicked.’”

John also expressed doubts over the effectiveness of rehabilitation programs in jail. “When my 12-month program finished, the two leaders said, ‘We’ve taught you everything about sex. So we’ve either cured you or we have made you into even better sex offenders’.”

A spokesperson for Corrective Services NSW said jails offered several major voluntary therapy programs for sex offenders, one of which was found by an evaluation to reduce reoffending by 70 per cent. Yet those who are still considered to pose a high risk of reoffending when due for release “can and do become candidates to be kept behind bars” or subject to “extremely intense monitoring and supervision in the community for a specified period,” she said.

Nestled amid regenerating native bushland on the edge of prison land in west Brisbane is a quiet strip of nine nondescript residential brick and fibro houses. Surrounded by wire fencing and red-lettered “KEEP OUT” signs, this is home to some of Queensland’s most notorious sex offenders. Officially known as a High Risk Offenders Management Unit (HROMU), the two-storey properties keep about 20 men suspended indefinitely between imprisonment and freedom. “F#ck off you dogs,” shouted an unidentified resident from his balcony when The Weekly visited the housing site last month. “I’ll kick your f#cking head in.”

The men are allowed to leave the housing, but are monitored 24/7 through their ankle bracelets, which are linked via GPS to an electronic surveillance unit, where corrective services staff track their every movement on a computer screen. If they enter forbidden territory, they are immediately contacted by mobile phone and ordered to retreat. Breaches can result in supervision orders being extended by years or even a return to jail.

Critics argue housing sex offenders together may ironically increase their risk of re-offending, especially if they share the same sexual preferences. Not only could it further legitimise the prospect of sex with children, for example, but it may lead to a sharing of ideas about grooming or finding vulnerable kids. Furthermore, their status as social outcasts living on the fringes of society is cemented at a time when they’re supposed to be re-integrating into normal society.

Keen to gauge the reaction of parents living in close quarters with some of the state’s most high-risk sex offenders, The Weekly spoke to families in the friendly middle-class suburb where the Brisbane HROMU is located. Most were unperturbed by the nearby presence of high risk sex offenders. “I wasn’t aware of it,” says Becky, 35, whose kids are playing at a local park. “It does make you feel more wary, especially with the kids, but this area does generally feel safe.”

“I would err of the side of caution over whether [high risk sex offenders] can be rehabilitated,” says another mother, Sandra, 38. “I think there needs to be more emphasis on stricter parole conditions and sentencing.”

Local shop managers were philosophical about safety.

“I reckon we’ve got more police around here than most places, with the prison here,” says one. Another, who has lived in the area all her life, says, “At least if [sex offenders] are down there, they are being kept a close eye on. Mind you, in this day and age, your next-door neighbour could be one and you’d never know about it.”

She’s right in that an estimated 90 per cent of child sex abuse happens at the hands of a friend, family member or trusted acquaintance, such as a babysitter or carer. It’s for this reason that child safety campaigners have moved away from focussing too much on the “stranger danger” message, instead teaching kids how to be assertive about protecting their bodies and speaking out.

Two years ago, WA became the first and only jurisdiction to allow public access to its sex offender register. Police Minister Liza Harvey said the state government was proud of the site, which had been “welcomed by the community” and had had 127,285 hits by mid-March, with no reports of vigilante action against offenders. Yet while it may be popular among concerned parents, the real threat is more likely to be found in their own backyard.

In some ways, accepting that paedophilia is a sexual orientation is more difficult because we can no longer banish it to the “evil monster” box. It is part of the human spectrum, uncomfortable as that may be – some are good people who will never hurt a child, others commit terrible crimes that cause untold harm.

On the other hand, humanising it also has inherent benefits, including preventing child sex abuse. It may make us more aware that it could affect people we know, for example, and make it easier for paedophiles to get professional help. In Canada, for example, there’s a growing move towards officially recognising paedophilia as a sexual orientation, while activists push for paedophile acceptance in The Netherlands.

So what became of Bobby? He is currently serving a jail sentence after pleading guilty to abusing several children and is seeking help for paedophilia. His mother is continuing to support him.

Meanwhile, John hopes to move in with his girlfriend and have his GPS ankle bracelet removed when his supervision orders expire this year. Although he still denies the charges against him, he knows he will probably never have contact with his ex-wife, daughters or grandchildren. “I just want a normal life,” he says. He will remain a registered child sex offender until he is 80.

And after more than a quarter of a century of marriage, Nicholas still has no plans to tell his wife about his innermost desires. “At times, I feel a bit guilty about it,” he says, “but it is frightening. We are very happily married and I don’t think telling her would help either of us.”

To parents like Anne, who discover their child is a paedophile, he offers the following advice.

“They should tell him that they love him, that he is a good person and they are confident that he can live a good life and avoid having sexual contact with children. They should then try to get him help.”

Asked whether he may have passed his paedophilia onto his own children, he replies quickly, “I sure hope not.”

This story was originally published in The Australian Women’s Weekly May 2014.