When Narelle Phipps suspected her eight-year-old son Neil might be gay, she decided to ignore her fears. Ten years later, when Neil was 18, she confronted him, twice, after he attended Mardi Gras. His answer wasn’t what she wanted to hear.

Narelle Phipps knew quite early that her son Neil saw the world through a different prism.

“I first wondered if Neil might be gay when he was about eight,” says Narelle.

“He was our only son, but he seemed so very different to the other boys.”

“He loved rhythmic gymnastics and he’d dance around on the deck, twirling coloured ribbons in the air. His sister is five years older than he is, but he joined in her jazz ballet classes and loved it, but didn’t seem to notice that he was the only bloke. He was a gorgeous boy who made a wonderful contribution to the family because he was so lovely.”

For the next decade, Narelle did what she now describes as “a wonderful job of burying my head in the sand”.

“I just pushed that to the back of my mind and carried on,” she says. “I don’t know why. Perhaps I was hoping that it would all go away and I wouldn’t have to deal with it. But I was wrong.”

Coming to terms with the reality of a homosexual child is a difficult prospect for many parents. More than one million Australians – about one in 20 – define themselves as gay or lesbian, though many believe a truer rate could be as high as one person in 12.

While some have no trouble accepting their children for who they are, others struggle in an emotional conflict that sometimes tears families apart. Not only must parents overcome their own prejudices, they must also overcome an overwhelming assault from some of the most powerful feelings in the human spectrum – fear, grief and even disgust – many times fuelled by misunderstanding, misinformation and ignorance, and all of them destructive in their own way.

Yet, as these case studies show, it does not always have to end in bitterness and recrimination, nor in family breakdown.

When Neil was 18, Narelle and her husband Keith, an engineering consultant from western Sydney, came home from a weekend away.

“We came home to discover that Neil had gone to Mardi Gras, the annual gay and lesbian parade in Sydney, with some friends and that he had worn his sister’s silver spangly dress.

“I sat down with him at the dining room table and asked him if he was gay and he said, ‘No Mum, I’m not.’ Two weeks later, I asked him again and this time he said yes.

To my eternal regret, I handled it badly. I told him I was devastated. He needed me to understand, but some part of me wasn’t really listening. It was awful. I’m so sorry about that. I’d had 10 years to get ready for it, but I didn’t.”

Narelle and Keith left on a pre-planned holiday to New Zealand the next day.

“At the time I felt guilty about going,” she says. “I cried my way around New Zealand for two weeks.

However, I knew at the end of that time, that the most important thing was for us to stay together as a family. That was my top priority.

I thought back to when Neil was eight. I thought if he is gay, then I’ll handle it and it will be Keith who will fall apart. In fact, it was the other way around. He was a tower of strength and I was a mess.”

Keith discovered the support group Parents and Friends of Gays and Lesbians (PFLAG). He and Narelle attended their first meeting two weeks after they got back from NZ. “I thought to myself,

‘God, what on earth is this going to be like? They’ve all got gay children!’” says Narelle. “I was off on some terrible selfish tangent.

“But it was at the PFLAG meetings that I found an outlet. You listen to people and tell your own story and one day you see there’s a light at the end of the tunnel. For six months, those meetings were my fix. I needed the support and knowledge that these people were in a similar position.”

What Narelle didn’t expect was the rich vein of self-awareness that she would eventually uncover. “I started to think about me, about my reaction,” she says.

“I realised that, perhaps unconsciously, that I had brought up my children in different ways. I’d brought up my daughter to be an independent woman, but I’d raised Neil to be a good husband. That was my expectation. So I had to make this colossal shift in attitude; that his partner was going to be a bloke.”

Then she found an affirmation that she memorised. It was, “I come from a unique family that gives me unique opportunities.

It’s a family unlike any other family I know. “It resonated with such power,” says Narelle. “I would say it over and over.

Finally, I came to the certain knowledge that Neil couldn’t change who he was, and the only change that was possible was in me. It would have to come from inside me.”

Today, Narelle and Neil share a close bond. Keith died from a brain tumour three years ago. Neil is 32, and a university drama graduate and aspiring actor. He recently appeared in an episode of Packed To The Rafters as a gay mechanic.

“I think it’s important for people, for your children, to know that the most significant people in their lives accept them for who they really are. It’s a sad thing if a parent doesn’t love their children enough to accept them.”

Gillian Maury has three children, two of whom are gay. Although there were a lot of tears shed, she is now a counseller for a support group for parents of gay kids.

“I never lost sight of the fact that we are a family”

Gillian Maury knew something had changed the moment she opened her door. Her daughter Veronique, an attractive 22-year-old law student, stood at the threshold, her long, dark hair gone, her head smooth and bald.

But what Gillian didn’t understand was just how dramatic a change it really was.

“I thought, ‘Well, that’s a rather extreme hairstyle,’ ” says Gillian, a mother of three, of her daughter’s symbolic act. “Veronique had been to a conference in Perth. She sat us down at the kitchen table and told us she was gay. I thought my world had fallen apart.”

Gillian, a school counsellor, and her husband, French-born chef Jean-Pierre, were stunned. “I was distraught, that’s the only way to describe it,” says Gillian, now in her late 50s. “Everything that I had hoped for in my future – weddings, grandchildren, this ideal picture, flashed in front of me and disappeared. I remember thinking, ‘Why has this happened to me? What did I do wrong?’

Then she said something I have always appreciated. She said, ‘Some people think this is a stage, but I can tell you that for me it’s not. It’s not a choice. It’s just the way I am.’ ”

Today, 14 years on, Gillian scoffs at her former perspective. “It was all about me, about what I wanted and not very much about my daughter or what she wanted,” says Gillian.

“I see that now, but I couldn’t see it at the time. I was too busy crying.” What Gillian experienced is common in such situations, and very real. Psychologists, she says, often refer to it as “grief for lost expectations”.

Gillian’s expectations were those of many mothers – that her daughter would marry, “in a white wedding with all the trimmings”, and one day provide her with grandchildren.

“I felt that evaporate in an instant,” she says.

Like the Phipps, Gillian and Jean-Pierre sought help from PFLAG . Although Gillian, particularly, had her doubts, she eventually found their support invaluable. “I was inconsolable, sobbing and sobbing,” she says.

“I was grieving for what I thought I’d lost. I still loved her, and my other children, but I discovered that in some ways that love was conditional on them doing what I expected of them. But I loved them all enough to find out more about what was happening, to her and to us.”

From Gillian’s viewpoint, PFLAG at first seemed a poor fit. “In the first meeting someone made a joke and everyone laughed,” she says. “I stormed out and burst into tears, thinking, ‘This is no laughing matter, what’s funny about this?’ Then a woman came out and put her arm around me. She said she had been through the same thing. What we learned was if you talk about it, you can find a way through it all. If you keep talking, then there is hope.”

Ron Nunan is an ex-Queensland police officer who was raised with staunch Roman Catholic beliefs. Ron and wife Dianne had to overcome their own prejudices to accept the fact that their youngest son is gay.

‘For my generation, being gay was the greatest taboo’

For Ron Nunan, the discovery that his youngest son, Mark, was gay was like “a hammer blow to the back of the head”.

“It was the very last thing I wanted to hear. I didn’t know what to say, I didn’t know where to turn,” says Ron, a former police officer whose attitudes sprang from a staunchly Roman Catholic religious upbringing and a lifetime’s accumulated prejudice against homosexuals.

“For my generation, being gay was the greatest taboo. When I was a copper, homosexuality was a criminal offence. The Church said gays were evil. And all of a sudden, there I was face to face with the fact that my son was one of those people.”

Ron and Dianne Nunan, in their early 60s, had four children – two boys and two girls. Mark was the youngest. At about 16, he had problems at school.

He became depressed and his grades dropped off. One night Ron asked him if there was something wrong. Mark’s reply shocked him.

“I was going through a bad time and was angry,” says Mark. “I blurted out that I thought I was gay. Dad told me it was just a stage and from then on he only referred to it as ‘my little problem’.”

Ron admits he didn’t handle it well, either. “I pushed it back under the carpet and hoped that it would all go away,” he says.

“I told him it was a stage he was going through and that it would work itself out.”

Mark confided in a family friend, who suggested he see a psychologist. During the next six months, Mark’s depression and grades improved and he seemed to be back on track. Yet the prospect that he may have a gay son gnawed at Ron like a canker.

“I was terribly homophobic,” Ron says. “Every day for the next 18 months I’d pray, ‘Don’t let him be gay.’ It was like a monster sitting in front of me. I used to say terrible things to him, things I’m ashamed of now. I used to tell homophobic jokes at the dinner table, awful things. I was trying to turn him around, to stop him being homosexual.”

“In my ignorance, I associated being homosexual with being a paedophile. I remember thinking, ‘How can I have a son who could be a paedophile?’ I know now that’s rubbish, but at the time I just didn’t want him to be gay.”

Mark finished high school and moved on to university. Early in his first year, Ron and Dianne confronted him. “Mum was crying when they came in and we all sat down,” says Mark. “Mum asked me if I was gay and I said, ‘Yes, I am.’ ”

“I wanted to take him to the doctor,” recalls Dianne. “He just looked at me and said, ‘That’s pointless, Mum.’

Ron sat down with Mark and asked him what he says may be the most important question he has ever asked anyone. The importance was not in the question but in Mark’s response.

“I said, ‘How could you possibly choose this lifestyle?’ ” recalls Ron.

“He said, ‘Dad, you’d have to be mad to choose the lifestyle of a gay. It’s not an easy life. You’d have to be crazy. But it’s not a matter of choice – it’s who I am.’

“Those words made me stop and think … it was the first crack of light at the door, the idea that it wasn’t a choice. A lot of religious groups say that homosexuals are evil, but I looked at Mark and I knew he didn’t have an evil bone in his body. I never lost sight of the fact that he was my son and that I loved him.”

For Mark, it was a relief.

“I had a sense that a massive weight had lifted off my shoulders, but that was tempered by the fact that I could see that weight had transferred itself to my parents.”

Mark gave them a telephone number for an organisation called Parents and Friends of Gays and Lesbians (PFLAG), run by parent activist Shelley Argent.

“Shelley saved our lives,” says Ron. “The first time I spoke with her, I cried like a baby. I was a real mess. I said, ‘I can’t deal with this; I’m an ex-copper. She said, ‘That doesn’t matter. My son’s gay and he’s still a copper.’”

Two weeks later, they attended their first PFLAG meeting with other parents who had been through similar experiences. It was a revelation. For Ron, the openness he encountered punched through his fears. “The thing that struck me most was the idea that you can’t change it – that it’s as impossible for Mark to be heterosexual as it would for me to be homosexual, and there’s not much chance of that happening.”

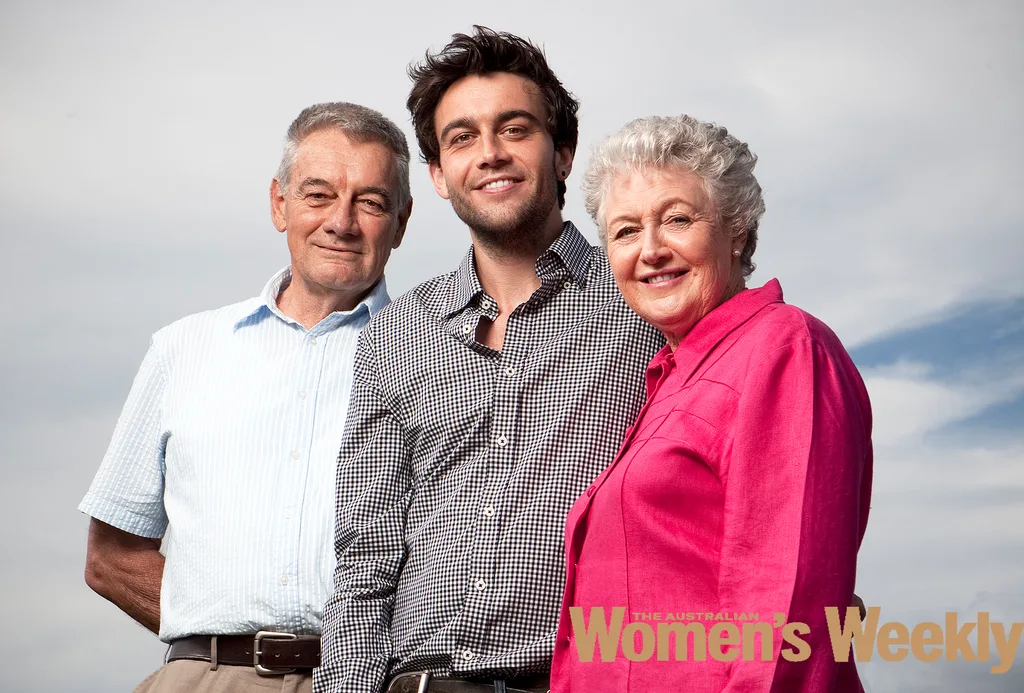

Today, Mark is 27 and a graduate in journalism and arts, though he is carving out a career as a singer and songwriter based in Melbourne. He says his parents are his greatest supporters.

“We’re great friends,” says Mark, who wrote a song dedicated to Ron and Dianne about their ability to accept him for who he is, one he still performs today.

“I am so proud of how far they have come. We have a much more open, adult relationship now. I don’t know what I’d do without them.”

Five steps to understanding

PFLAG’s Shelley Argent has this advice for parents who think their child is gay.

1 Educate yourself about homosexuality and seek support for yourself and your son or daughter.

2 Give yourself time to overcome your fears and anxieties.

3 As a parent, you have done nothing wrong and neither has your son or daughter. Homosexuality is a natural sexual orientation.

4 Be mindful that depression and suicidal ideas can be an issue for the person coming out.

5 The greatest gift you can give your son or daughter is acceptance and understanding.

For more info, go to PFLAG to find a group near you.

0A version of this article was first published in the January 2011 issue of The Australian Women’s Weekly. Photography by Pip Blackwood