Aaron Cockman, 42, Margaret River, WA shares his horrific story:

I shuffled the pile of bills in my hands and it made my stomach sink.

“We’re two months behind on the mortgage, the credit card’s maxed, and we’re building a house,” I sighed to my wife, Katrina, in frustration.

I worked as a carpenter while Katrina home-schooled our four kids: Taye, nine, Rylan, eight, Ayre, seven and Kadyn, four.

Money was tight, but there was plenty of love in our family.

The kids were the light of my life. My son Ayre was my little shadow and I was sure he’d follow in my footsteps to become a carpenter, too.

But when the reality of our huge mortgage really started to hit home, we had to borrow from our parents.

Trouble was, our expenses were far more than my single wage brought in.

We soon realised it would be best to move in with Katrina’s parents, Peter and Cynda Miles, who lived just minutes away, to save money while I finished renovating our house.

Taye Cockman.

(Image exclusive to Take 5)Peter, a quiet, introverted man, was a good mate, while Cynda was a doting granny who loved helping out with the kids.

“Thanks for this,” I said to them. “Once we’re back on track, we’ll get out of your hair.”

I worked my guts out so that’d happen sooner rather than later.

The stress of it all meant Katrina and I had our ups and downs.

I hoped that life would be easier once our debts were cleared.

But Peter and Cynda blamed me for our financial problems, and Katrina usually sided with them.

Many times, I bit my tongue.

I knew that things hadn’t been easy for my in-laws: Katrina’s brother, Shaun, had taken his life 15 years earlier, and Peter’s own mental health wasn’t great after suffering a nervous breakdown.

Just two months after we’d moved in, Peter barred me from the property.

“You’re not allowed on this driveway anymore,” he thundered.

Devastated and confused, I moved back into our home, which was now complete except for part of the interior top storey.

Rylan Cockman.

(Image exclusive to Take 5)I wasn’t even allowed to see my kids anymore.

I tried talking to Katrina about what was happening, but she refused to discuss it.

Using her dad’s lawyer to write formal legal letters, Katrina claimed that I’d abandoned my family and demanded $900 a week, plus medical and vehicle expenses.

In a good week, I made $1500, often much less. To pay the mortgage, Katrina’s rent to her parents, plus the other bills was impossible.

My parents offered to pay to finish the house and fund a rental property for us.

“Let us buy the whole thing out, including the debts,” Dad said.

But through their lawyer, Peter said no.

My parents’ idea made sense to me, but Katrina rejected the idea, claiming I’d flouted building codes.

My dad and sister helping build the house.

(Image exclusive to Take 5)It wasn’t like her to be so aggressive. I could only think her parents had brainwashed her; they’d always had a lot of influence over her.

She sprung me with a stop-work order from the council, preventing me from finishing the build.

My lawyer explained that agreeing to an uncontested Violence Restraining Order (VRO) was the best way to see the kids as soon as possible.

All I wanted was to be with them again, so, ridiculous as it seemed, I agreed to an uncontested VRO, which meant I couldn’t contact Katrina or the kids until the court said otherwise.

I didn’t care about the VRO or even really understand what it was – I just wanted to see my kids.

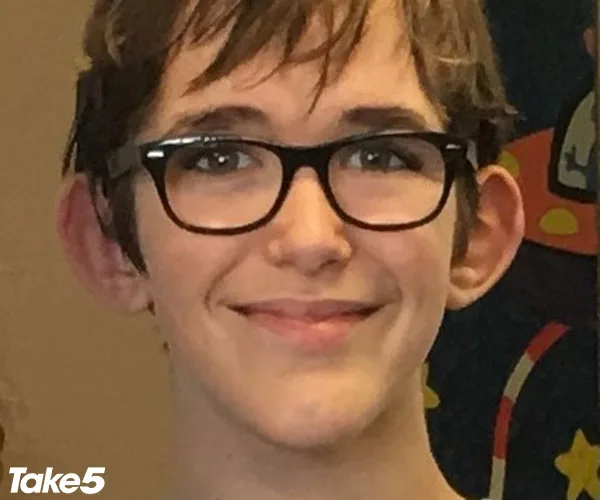

Ayre Cockman.

(Image exclusive to Take 5)Then I saw Katrina’s VRO statement. She’d alleged I was abusive to her and our children.

I was speechless – I’d never raised a hand to her or the kids.

It took six months before I was allowed supervised visits. In that time, I suffered panic attacks, couldn’t sleep and drove around town, desperate for a glimpse of my kids who I missed so much.

Sometimes I wondered if I’d ever see them again.

Taye, a talented artist, was a creative girl who could paint and draw beautifully.

Rylan, our gentle giant, had size-13 feet. He loved history and reading comics.

I dreamed that Ayre would be my little chippy apprentice one day.

Kadyn, the baby, was a funny little boy who said exactly what was on his mind.

“I see why estranged dads kill themselves,” I told my parents, utterly heartbroken.

“Why is Katrina doing this?” Dad asked.

“Her parents are behind it,” I replied.

Peter wasn’t the sort of bloke to sit down and chat over things. His response to a problem was to fight, pushed on by Cynda.

Dad became very worried about their hostility and Peter’s stability.

By the time I got supervised visits with the kids, they’d been turned against me and would only show some affection by the end of each visit.

“Go away, Dad,” Taye said once, spitting on me.

I was shattered.

“Katrina will make sure you and your parents never see the kids again,” Cynda snapped one day.

My in-laws, Katrina and the kids moved to a farm in Osmington, 20km from Margaret River.

Meanwhile, an investigation by the Department for Child Protection and Family Support cleared me of all the allegations.

Katrinia, Peter and Cynda with the kids at a family wedding.

(Image: ABC News)The Family Court made an order about the kids’ living arrangements.

The law prevents me from talking about the specifics, but they continued living at the farm, in defiance of the order which wasn’t enforced.

I rarely saw my children at all then.

But when I did, it was just me, them and Katrina. With her parents out of the picture, things were far more civil between us.

It still took the kids time to warm up to me because these meetings were so infrequent, but soon it was just like old times.

“I miss you, Katrina,” I confessed to her one day.

“Miss you too,” she smiled.

Later, we snatched some time alone and made love.

“Don’t tell anyone,” she hushed afterwards, fearing her parents would think she’d betrayed them.

I couldn’t understand why something that could have been sorted out with some discussion had escalated so quickly, but Katrina’s parents had always had a huge influence over her.

Kadyn Cockman.

(Image exclusive to Take 5)I knew she was too scared to go against them.

One time Katrina and I took the kids to the cinema, then went out for ice-cream afterwards.

“It’s just like old times,” I grinned happily.

The next time I saw the kids, we went snorkelling.

Although the water was freezing, none of us wanted to end the fun and go home.

Finally, things between me and my family were getting back on track.

Then, a few weeks later when I was at work, I got a voice message from the police asking to see me.

They didn’t say what it was about, so I figured Peter and Cynda had made another complaint about me.

Rylan when we went snorkelling as a family.

(Image exclusive to Take 5)As I wandered towards my workmates to tell them I had to go, they were gathered around the radio, shocked by the news being broadcast.

“Four kids and three adults are dead near Margaret River,” one of my mates sighed.

My heart sank… surely not?

“Mate, I think that’s my kids,” I stammered.

I’m not sure why, but somehow I just knew.

My whole body started shaking, as I wondered if my instincts were right.

The police soon arrived.

“Is it true? Is it my kids?” I asked one officer.

He nodded and, in that small action, my whole world came crashing down.

This isn’t happening, I thought, frozen with shock.

Kadyn and me, in happier times.

(Image exclusive to Take 5)At the station, officers explained my three eldest, Taye, 13, Rylan, 12, and Ayre, 10, had been shot dead as they slept.

Kadyn, eight, had been with Katrina, 35, in her bed and they’d both been shot dead too.

Cynda was dead on the living-room floor.

Peter had killed them all, then called the cops before turning the gun on himself.

The police showed me a suicide note Peter had left, which said I should get the contents of the house.

At first I thought he was leaving me everything in the house.

But I soon realised that’s not what he meant. By ‘contents’ I think he meant my dead children.

It was too wicked to bear: I wanted to die to be with my children. What else was left for me to live for?

As news of the massacre spread, it was called Australia’s worst mass shooting since Port Arthur.

Somehow, I got through the funeral, but the memory of four small coffins lined up will haunt me forever.

For months afterwards, I didn’t sleep or eat and existed in a permanent daze.

People wondered why Peter would do something so twisted and cruel.

Ayre and Kadyn.

(Image exclusive to Take 5)I believe he didn’t want to live anymore and decided to take his whole family with him, so they wouldn’t experience the pain of losing him.

Getting through each day has been hard when I don’t really have anything or anyone left anymore.

I have nightmares about the kids’ final moments. Sometimes I dream they’re still alive. I still love and miss Katrina as well.

I’ve since set up the aaron4kidsfoundation in association with For Kids Sake organisation.

Together, we’re campaigning for a fresh approach to family separation and divorce – treating these as a health and social issue, instead of a legal issue involving family courts.

I’m a father of four but, thanks to our broken legal system, ashes are all I have left of my beloved children.

One day, I’ll scatter them in the ocean – but not yet.

I lost my kids to a horrific tragedy and I’m not ready to let them go forever.

Philip Cockman, 65, Geographe, WA.

My son Aaron put his head in his hands and sobbed.

“I just wanna see my kids,” he wept.

He’d been driven to tears by lawyers acting for his estranged wife, Katrina, and her parents, Peter and Cynda.

Aaron was strong, but he was still only human.

“How much more can he take?” I asked his worried mum, Kim, later.

At first, they’d seemed like the perfect family. Aaron adored Katrina, but she could be controlling.

Insisting the kids were autistic, she said she knew how to treat them – with alternative therapies, special diets and medications.

We weren’t allowed to wear perfume or aftershave when we visited, as Katrina insisted it would affect the kids’ behaviour.

When they ran into financial trouble, Peter demanded they pay back the $45,000 he’d put into their half-finished home. Aaron continued to pay this off weekly until it was settled.

Then they threw Aaron out of their house. I met up with Peter and Cynda at Katrina and Aaron’s place, hoping to resolve things.

“This is all bulls**t. I just want this place finished and sold so I can get my money back,” Peter said.

Kim and I had put money into the house, too. With that common ground, I thought we had something to work on.

But Cynda wasn’t having any of it.

“Men! You all disgust me,” she sneered.

A fortnight later, they and Katrina began legal action against Aaron, claiming he’d abandoned his family.

We made an offer to purchase the debt, including Peter’s, but they refused, issuing stop-work orders on the house.

They made false allegations and groomed the kids to hate Aaron and us.

We hardly saw the kids over the next few years.

Peter and Cynda became so hateful, I insured Aaron’s life, fearing Peter would kill him.

“I can’t believe it’s come to this,” I said to Kim.

From left: Aaron, Katrina, Rylan, Kim, Taye, Kadyn and Ayre.

(Image exclusive to Take 5)For them, it was about winning at all costs, not what was best for the kids.

They spread rumours around town that Aaron was an abuser.

He tried not to burden us with it, but I knew it was destroying him.

I was at work one day when my son-in-law, Shane, called in tears.

“There’s been a shooting at Peter and Cynda’s,” he cried. “The children have been shot, adults too. Aaron can’t be found.”

I wept for everyone, including Aaron, who I thought was dead in a ditch somewhere, killed by Peter. I’d seen how irrational and angry he and Cynda were.

It took 90 minutes before I heard he was safe. I knew instantly that Peter was responsible for the murders and that they could have been avoided.

I’d been a senior prison officer. The world I’d worked in was structured.

Family law wasn’t like that.Pitting lawyers against each other in a custody fight gave them a licence to create hate and print money.

Exhausted by legal fights, I believe Peter had had enough.

Aaron (third from left) with his siblings and parents.

(Image exclusive to Take 5)Using my experience with the case managers of violent offenders, I’ve been thinking about the changes that could help prevent a repeat of a family tragedy like ours.

First, VRO applications must be examined and graded. One lawyer should act for both parents and on a set fee.

There must be mental health assessments and mediation.

Then, all orders, reports, access restrictions and supervision have to be dealt with quickly and treated as a priority to avoid mental health harm.

Any court orders have to be enforced and reviewed.

Now, Aaron’s called for a Royal Commission into the Family Court.

My son is an honest man, trying to make something positive come from this avoidable tragedy.

If things don’t change, more kids will die.

To help Aaron’s campaign, learn more about the Aaron 4 Kids Foundation here. Any proceeds from this article will go to this non-profit organisation.

If you or someone you know is struggling to cope, contact Lifeline on 13 11 14 or visit the Lifeline website.