Aboriginal leader Lowitja O’Donoghue has received many honours over the course of a long life: Commander of the Order of the British Empire, Australian of the Year, National Living Treasure, Companion of the Order of Australia, and even Dame of the Order of St Gregory the Great, a papal honour.

As Chairperson of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission, she led a $1 billion organisation with fierce integrity. She sat opposite Prime Minister Paul Keating to negotiate the first native title laws.

In 1996, she was a contender to be Governor-General, and had Australia voted to become a republic, she would also have been a contender for the nation’s first president.

Keating called Lowitja “a remarkable Australian leader”. Indigenous lawyer Noel Pearson called her the greatest Aboriginal leader of the modern era: “the rock who steadied us in the storm”.

But when Lowitja was born in 1932 to an Aboriginal mother and a white father in the harsh, ruggedly beautiful landscape of Central Australia, the expectations for her life could not have been more different.

At the age of two, Lowitja was handed over to the missionaries of the Colebrook Home for Half-Caste Children in Quorn, South Australia, and cut off completely from her people and her culture. She would not see her mother again for more than 30 years, while her father faded from her life altogether.

Some of those who were children at Colebrook will carry the ache of being separated from their mothers all their lives, while others describe it as “a loving sanctuary” and say that they were not stolen from their mothers but saved – from violence, or abuse, or poverty.

One of the children, Faith Thomas, remembers constant love and attention. Another, Nancy Barnes, will write of her time at Colebrook: “We didn’t miss out on anything, as I recall. Except perhaps our mothers.”

For Lowitja, Colebrook was both childhood and deprivation; questions that no-one could answer: Who am I? Where is my mother?

It was a place of rigid discipline and joyless religious observance, bad food, and endless praising of the Lord. It was the ringing of the triangle that hung near the well, and being punished for “childish things”.

The sting of a strap soaked in water and allowed to dry to make it harder. “I am sometimes identified as one of the ‘success stories’ of the policies of removal of Aboriginal children,” Lowitja says.

“But, for much of my childhood, I was deeply unhappy. I felt I had been deprived of love and the ability to love in return. Like Lily, my mother, I felt powerless.”

“And I think this was where the seeds of my commitment to human rights and social justice were sown.”

In this extract from Lowitja, the authorised biography of Lowitja O’Donoghue, she is reaching the end of her 15 years at Colebrook, where missionaries Ruby Hyde and Delia Rutter prayed to God to provide for their house of many children.

Lowitja is greeted by Peter Garret inside Parliament House ahead of a historic apology speech by then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd in 2008.

(Getty.)At the Colebrook Home for Half-Caste Children, Violet O’Donoghue runs through the house, bare feet padding on the floorboards, calling out for her little sister. “Iti,” she calls, using the Pitjantjatjara word for baby. “Iti …”

Lowitja is “the baby”, although by now she is a child, the youngest of the O’Donoghue children at the Colebrook Home. Vi is her protector. Their bond will run deep all their lives.

It will be Lowitja’s earliest memory, the loving sound of her sister running through the house calling for her, and then, as she gets older, riding on her brother Geoffrey’s back with her feet tucked into his pockets, all the two miles to school.

It is a crowded house, full of children taken from their parents and told to forget, watched over by spinster missionaries Ruby Hyde, who is short and stout with hazel eyes that see everything, and Delia Rutter, who is small and thin and gentle.

The missionaries are devoted to God and to the children; but at night, when the house is quiet, a child is often crying.

Lowitja does not feel loved. She is fond of Sister Rutter, but regards Matron Hyde as cold and stern, and calls her by the Pitjantjatjara name the children give her: kungka pikati – “the angry woman”.

Lowitja is often in trouble: “I remember in my very earliest days standing up for what I believed in. One of the earliest memories I have is of coming between the matron and the strap.

I would often stand in the way when the strap was intended for others, with the result being that I, too, got a beating.”

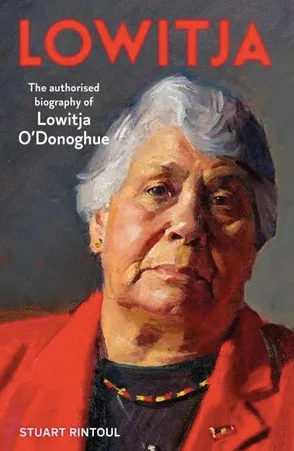

Lowitja, The authorised biography of Lowitja O’Donoghue, by Stuart Rintoul. Available via Booktopia here.

Lowitja (second from left), with other pro-republic Indigenous leaders Professor Marcia Langton, Patrick Dodson, Gatjil Djerrukura and Peter Yu, outside Buckingham Palace where they met with the Queen, on 13 October 1999.

(Getty.)The children are told that Aboriginal culture is “of the devil”. They are forbidden from asking questions about their past, their parents, and they are forbidden from speaking their native languages.

So, out of earshot of the missionaries, they make up their own secret “Aboriginal” words, and cling to those they remember, including the Pitjantjatjara words tjitji tjuta – “many children”.

When new children come into the home, they huddle around them and ask the questions that the missionaries will not answer: “Do you know my mother? Do you know where she is?”

In this way, Lowitja learns that her mother’s name is Lily, that she is “a full-blood Aborigine”, and that she is living “up there … in the bush”.

“Our hearts ached to know who we were, where did we come from, where were our mothers, and who were our fathers, and why wouldn’t they tell us. These words were never spoken, so the ache continued.”

Two years after she arrives at the home, an article appears in the Adelaide Advertiser, marvelling at the transformation of the Aboriginal children: “Those who have seen the Colebrook Home children are surprised by their charm, their intelligence and the fact that they are ‘like ordinary children’.”

It is only the training of a Christian home that has made them so. When they were brought in from the bush, they were wild, frightened, dirty and ignorant. Few of them had known anything of civilised life.”

A spokesman for the home tells The Advertiser: “The Home training has two objects: first, to make Christians of these children, and second, to merge them into the white population.”

“As they are half white, it is better to develop in them the instincts of Europeans, and to make useful citizens of them, than to leave them in camps to become Aborigines.”

WATCH BELOW: Meet contemporary Aboriginal artist Rachael Sarra. Article continues below.

The missionaries rely on faith and charity – God’s provision. Sometimes the baker bakes too much bread, or burns the crusts, or the greengrocer has left-over cabbages, or someone brings them a load of wood, and then the missionaries ring the triangle that hangs by the well and the children have to run to thank the Lord.

For every act of charity they receive, they sing the hymn Praise God from Whom All Blessings Flow:

Praise God, from whom all blessings flow;

Praise Him, all creatures here below;

Praise Him above, ye heav’nly host;

Praise Father, Son, and Holy Ghost! …

At mealtimes, the children line up on the veranda and march into the dining room, singing Marching Beneath the Banner.

They sing Onward Christian Soldiers and the Colebrook hymn, in which little girls serve Christ and boys are washed from sin. All her life, the hymn will come quickly to Lowitja’s mind:

Christ paid the debt for all the little children, Christ paid the debt for us all; Christ paid the debt for all the little children, in the Colebrook children’s home.

Happy is the girl who is serving Him, happy is the boy who is washed from sin; Never to a child will the Lord say no, So let us all to the Saviour go; For Christ paid the debt for all the little children, in the Colebrook children’s home.

And to be washed of their sins, they sing Whiter Than Snow:

Whiter than snow, yes, whiter than snow, Now wash me, and I shall be whiter than snow.

On Sundays, the children go to church, three times. Sometimes they go in Matron Hyde’s car, the one she calls Jonah, and then later in the one she calls The Whale: “We’d all climb in, the big girls first and we little ones over the top, sitting on their knees. “

“There was always such a fuss made by the big girls about their stockings. ‘Don’t crease our clothes’, they’d warn us. And ‘don’t ladder our stockings’.”

Some go to the Salvation Army and some to the Methodists, where they play in the band and sing in the choir. No games are played on the Sabbath; but one of the big girls, Miriam McKenzie, has a love and gift for music and plays a steel guitar.

Colebrook is also climbing trees and playing in the creek and games of Kick the Tin and Knucklebones.

Sometimes they find wildflowers as they walk to school along the highway into Quorn, scrambling over the dry rocks of the Stony Creek and the equally stony Pinkerton Creek.

Or they jump a fence to chase a kangaroo and forget to go to school altogether.

At the edge of town, where a park will later be created to commemorate the pioneers, the white children at the Catholic school, alongside the Church of the Immaculate Conception, see them coming down the road, all the Colebrook children, and taunt them with a murderous rhyme: “N**r, n**r, pull the trigger.”

And the Colebrook children chant back at them: “Catholic dogs, jump like frogs, in and out of the water.”

In the town, they pass a pretty house. To Lowitja, it looks like something out of a picture book. “That’s the best house in Quorn,” she says, over and over. “One day, when I’m older, I’m going to buy that house.” Ad one day, she does.

At night-time, they pray together: “Gentle Jesus, meek and mild, look upon a little child.” After which, in (mission historian) Violet Turner’s pungent expression, they drift into “the land of forgetfulness”.

Lowitja worked with Martin Luther King III, son of legendary civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jnr, to promote a five charity fundraising tour during National Reconciliation Week in 2002. The tour aimed to aid in funding community education and development of Indigenous leadership.

(Getty.)In Turner’s expurgated telling of it, in her book Pearls from the Deep, there is no sadness, or longing, only the joy of salvation:

“Nothing pleases the children more than to gather around the little organ and sing hymn after hymn. They know by heart dozens of hymns and choruses, and a number of chapters of Scripture. As they sang, our eyes wandered around the group, and we pictured each child as he had been when first he came to the Mission. We could see again, in memory, the frightened, wild faces, the dishevelled hair, the expression of blank ignorance, almost stupidity, that had characterised them then.”

“Now, what a change had been wrought by the grace of God! Faces eager and full of animation, eyes sparkling with health, voices raised in songs of praise to Him who had called them out of darkness into His marvellous light – such they were now, and our hearts followed their voices in praise for what He had done.”

Lowitja (second from right) with Nicola Severino, Nova Peris-Kneebone, Evonne Cawley, Ernie Dingo, and Nicky Winmar, holding the Australian 2000 Olympic torch at Uluru, June 7, 2000.

(Getty.)The children are very young. In November 1941, the secretary of the United Aborigines Mission, Reverend A.B. Erskine, writes to South Australia’s chief protector of Aborigines, William Penhall, saying the mission prefers children to be seven years of age or under: “Over this age it becomes increasingly difficult to control them, as they have learned so much of the bush ways and habits.”

In photographs, Lowitja is a little girl in grey second-hand clothes, wishing she had something bright and frilly to wear.

She tries desperately to be noticed and spends hours brooding over how she has come to be here, without a mother and a father, and why no one comes to get her: “When I was very tiny, I would ask, ‘Who am I, who is my mother, who is my father, where do I come from?'”

By the time she is seven or eight, she stops asking: “I wasn’t getting any answers. The other children in the Home became my family.”

This is an edited extract from Lowitja, the authorised biography of Lowitja O’Donoghue by Stuart Rintoul, published by Allen & Unwin. On sale now.