Karen Milligan and Gary Johnson hadn’t planned to take the boat out on what would be their last day on Earth together, but the weather was perfect and the warm cerulean waters off the coast of Esperance were calling to the seasoned scuba divers.

It was January 2020, and the couple had just enjoyed four idyllic days diving at Woody Island, searching for groper fish in the Recherche Archipelago. Gary was due back at work the next day, so they thought, ‘One more dive, why not?’

They packed up their gear and Karen’s underwater camera, and headed for one of Gary’s favourite sites – the shallow water near Devils Rock, not far from the home they shared.

“We anchored and it was a beautiful day. Lovely weather. We sat in the boat probably for 10 to 15 minutes, putting on our gear. Just chatting and just being,” says Karen.

Gary and Karen were keen divers who wanted to complete one more dive before Gary went back to work the next day.

(Image: Dan Paris)The sun was warm on their faces and they felt utterly at peace. This final dive would mark the end of a much-needed Christmas break after a challenging couple of years.

Over the previous 18 months, Karen had been retraining as a psychologist while flying in and out of Perth on government contract work. She and Gary had hardly seen each other, and it was making them miserable.

“We wanted to be living together; we didn’t want all this time apart,” she says.

They’d met later in life, when Gary came to Karen’s rock’n’roll dance class and asked for private lessons. Karen had a policy of not dating customers and for eight months she stuck to it, until one night Gary found her crying outside the dance studio.

“Something quite bad had happened. I was outside bawling my eyes out and he came along,” she says. Gary consoled her and “from that moment, there was never a time when I didn’t love him to bits. He was truly the most wonderful man I’ve ever met.”

Now they looked forward to the next stage of their lives.

“Over the holidays we’d reignited our love story,” she says. “We were happy, content. We’d actually made love that morning.”

Together, they prepared to enter the water. They put on their buoyancy compensators – vests that would help them float on the surface and keep them stationary underwater – and Gary strapped a knife to his leg. They’d performed this same routine many times before, Gary rolling over the side of the boat and Karen easing off the back with her camera.

“He used to go straight down and tie off the anchor. Sometimes in Esperance the wind changes very quickly, so if we tie off the anchor it means we won’t be stuck out there with no boat,” Karen says. “I jumped in pretty quickly after him, but I was probably 10 or 15 metres above him.”

Once submerged, she could see that the day was just as beautiful under the waves as above. The water was crystal clear, and in retrospect she suspects other sea animals sensed danger, which was why the visibility was so amazing.

Karen made her way down the anchor line, which had drifted over a sandy hillock. Gary had disappeared with it. Whenever they were diving and they lost sight of each other, Gary would check to make sure Karen was okay. Suddenly, there he was.

“You would never believe how big they are. They’re so strong.” Karen on first sighting the shark that attacked Gary.

(Supplied)“He popped up. That’s what I remember. He had a sort of …” she falters. “His limbs were all loose and his eyes were really big. I thought he was playing. I thought, ‘We’re in love, isn’t this fabulous?'”

She swam towards him, but when she cleared the dune, she got a shock: “In front of my face was this huge, huge tail swinging back and forth.”

Karen felt a pang of panic, followed swiftly by relief. A shark’s fin is vertical, she told herself, and this fin seemed horizontal, like a whale’s. But then came a flash of white, and the illusion was shattered.

“The tail was at a different angle,” she says. “The shark was on its side.”

Now the terror was real and her instincts kicked in.

“You get this big wham of fear. ‘That’s a shark! It’s got Gary! I’ve got to go.’ You go into coping mode. ‘What am I going to do to help Gary?'”

Karen’s husband was a muscular man of 6ft 4in, but the shark was immense.

“It was five metres, but it’s not the length that’s the fearful thing,” she says. It’s the muscular girth of the beast, like a small car. “You would never believe how big they are. They’re so strong.”

Great white sharks occur in coastal, shelf, and continental slope waters around Australia, including WA.

(Image: Getty)Karen had her camera – a potential weapon – and lunged at the creature with it.

“I swam forward and tried to hit the shark tail,” she says. She swung at it again and again, but couldn’t tell if she was landing any blows. If she was, it wasn’t making a difference. The shark was thrashing – the force was incredible – and it was kicking up sand, making it hard to see.

Karen decided to go for its nose, “because that’s where they’re the most sensitive”. She pushed through the roiling water towards its head, but she couldn’t get close enough and she couldn’t see.

“It was very wild. The water’s turbulent. It’s full of blood. You know those dreams where you run along, and you can’t get anywhere …He’d come from behind. The shark had bitten [Gary] from behind on his left shoulder … I suspect it was a major battle between him and the shark. Gary’s fighting for his life!

“Then all of a sudden, there’s a flick of the tail and the shark’s gone. The speed of these animals is amazing. I didn’t see what direction it went. This was all in moments. Seconds. But it felt like it went on forever.”

As the water cleared, Karen searched desperately for her husband. He wasn’t lying on the sea floor and she feared the shark had taken him when it bolted.

Karen describes Gary as fighting for his life against the massive shark.

(Image: Supplied)“I thought, ‘What do I do?'” Adrenalin was still pumping through her veins. She swam for the anchor chain and began to pull herself towards the boat. Then, as she reached the surface, she saw Gary. He had broken free and hooked his arm over the top of the anchor chain.

“I thought, ‘Oh my God, he’s here and he’s alive!'”

Karen threw her arms around her husband. His diving gear had been ripped off and his wetsuit was torn to shreds. The whole top half was totally gone. “But he looked perfect,” she says.

As she eased him off the anchor line, he took a deep breath. “I felt him relax and I thought, “He knows I’m here.'” She took him by the arm and towed him towards the back of the boat, whispering to him as she swam. “I’ve got you. I’ve got you.”

Karen pauses in her story here as she relives the moment. The tears come and her voice quavers.

“I got him halfway, then he rolled over and I saw his left arm was missing,” she explains. “His eyes were huge. Bigger than 50 cent pieces. It’s what happens if you don’t get enough oxygen. But I believed he was still alive. My idea was to get him on the boat as quickly as I could.”

But she couldn’t lift him out of the water.

“Every time I tried, the wind would blow me off and we’d drift away.”

WATCH: How to reduce your risk of shark attack. Story continues after video.

She made three attempts, battling against the waves and the wind with her beloved still in her arms. After they were knocked back down for a third time, she realised she would have to climb onto the boat and pull him up.

Karen removed her vest, wrapped it around Gary and pumped it up to keep him afloat. But as she manoeuvred him, she realised her cherished husband had left her. He had died there in her arms, and now they were drifting.

“I thought, ‘I’ll just hold him and maybe a boat will come past. I’ll just drift with him,'” Karen says. But she knew it would be hours before anyone would notice they were missing.

“All I wanted to do was hang on to him and drift with him,” she says. But she thought about her daughter, Hannah, “and how I couldn’t do that to her. I had to let him go.”

Karen swam to the boat and called for help. No one answered. She phoned a friend who called the police. And then she rang her sister.

“I said, ‘You’re going to have to come down quick. This is just awful and I’m not going to cope.’ I was just sitting on the boat. I kept my sister on the phone.”

She pauses again as the awfulness washes over her. She doesn’t know how long she was there before she saw the rescue boat approach. “That’s when I let it all go,” she says.

“I’ll just hold him and maybe a boat will come past. I’ll just drift with him,'” Karen on her terrible ordeal as she tried to save Gary.

(Image: Dan Paris)Karen’s memory of the aftermath of the attack is hazy and disordered, but there are two moments that will stay with her for the rest of her life.

“I call it the hug and the hat. It’s humanity and humour, and they’re the things that got me through this,” she says.

When the rescue boat found her, she was reeling.

“I would say I was in acute shock. I was not there after that. I was numb.” But she remembers climbing aboard the vessel, where there was a police officer who reached out to her and pulled her into a tight hug.

“I will remember that hug forever,” says Karen. “It was so needed. He was a big, tall, cuddly guy, and it pulled me back from wherever I was. I came back to earth. You can’t believe how important that hug will remain in my life.”

As the rescue boat sped back to shore, Karen collapsed onto the floor. She refused the crew’s pleas for her to put on a life jacket. Then the nausea rolled over her.

“I said, ‘I think I’m going to be sick. Is there anything I can be sick into?’ Suddenly this copper’s hat came under my head,” she laughs gratefully.

“I couldn’t thank those people enough. A lot of humanity happened to me, from really good people.” But at the time, the enormity of it all was crushing. “I kept saying, ‘Knock me out, knock me out.’ I don’t remember much until my sister arrived.”

In the days that followed, Karen was given antidepressants, but she soon took herself off them.

“He brought the better person out in me because he was the better person,” Karen on her beloved Gary.

(Image: Supplied)“In some ways I think that, if you miss the process of grieving, you won’t be as healthy as if you just go through it,” she says. “Sometimes I wanted to wail because the pain was so great, and I did. I’d wait until I got home, and then I’d go into the hallway and I’d bang my head against the wall and wail because it’s physically painful.”

At Gary’s memorial, she was inundated with stories of people whose lives had been touched by her husband. One in particular stands out in her memory.

“The cleaner of the gym Gary used to go to most mornings came and said how he’d always had time to say hello to him, have a chat to him. Just because that’s who he was.” Everyone recalled his kindness. “He brought the better person out in me because he was the better person,” she says.

Around that time, Karen was being hounded by the media. Family members fended them off, but she did give one interview. In it, she got across an important message. She knew Gary’s traumatic death would give rise to calls for sharks to be culled, and she knew he would not have wanted that.

“I think Gary would have been horrified to think his death was used to promote an agenda that he was completely against,” she says. “He’d made this personal choice to take the risk and go out there. We both did. We were aware of it. We made that choice. We were just unlucky.”

They had both given generously to organisations that cared for the marine environment.

“It was his dream to make sure we did the best we can for the ocean,” Karen says. “He’d wander through town with his Sea Shepherd [Conservation Society] hat on.” And when friends came on board his boat, he’d give them a reusable water bottle. “That’s how he’d gently change people. I just thought he was amazing,” she says.

Karen has tan lines and laugh lines from a life spent happily in, on and around the water. Two years after that traumatic day, she can look back and remember how fortunate she felt that Gary had come into her life.

“The 15 years I had with Gary were the fullest of my life,” she says. “I’m so lucky to have had them. Most people never get that opportunity. But I did.”

She has found ways to help herself heal. She tells jokes – sometimes dark jokes – to put others at ease “because humour was so important for me and it still is”.

She knows Gary would have wanted her to laugh. “When the shark took him, I thought, ‘The crazy shark, he just got one of the good guys.'”

She has also created the Gary Johnson Foundation to promote ocean health and support the development of a marine park off the Esperance coast. She spends her time collecting data, in the form of stories from locals who have lived and fished in the area for decades, to get an understanding of what the ocean used to be like and set a baseline for what is possible.

“Everybody looks at Esperance and says, ‘It’s not broken, so don’t fix it’,” she says, “but from our perspective it was breaking quickly. When you talk to the old-timers or people who have had 50 years’ experience, they say the bay used to be really alive with fish.”

The WA town of Esperance and the magnificent beaches of Cape Le Grand National Park are famed for their beauty.

(Image: Getty)The WA government has announced it will establish a marine park off the south coast of the state, and Karen is on the reference committee. As she goes about this work, she keeps Gary in her heart and mind.

“That’s the research I’m doing for Gaz, and I think he would love it,” she says. “You always look back,” she adds, “and say, ‘Could I have done anything more?'” But she knows she couldn’t.

0“Everybody says, ‘You’re really brave.’ I had to overcome a wee bit of terror, but you don’t really have time. It’s just something you do. I think anyone would do it for someone they love.”

Karen still dives and says she has no fear of sharks. To her, the ocean will always be sacred. It is where she lived her best days with her love, and where she farewelled him. As awful as it was, there are parts of that memory that she will forever hold in her heart.

“I saw him sinking down and it was like he was looking at me, even though he was a long way away,” she says. “He looked very natural. It was gorgeous. I’m so glad he wasn’t put in a coffin. I thought it was a really lovely burial, giving him back to the ocean.

“It gives me solace.”

To learn more about the work of the foundation, visit garyjohnson.foundation

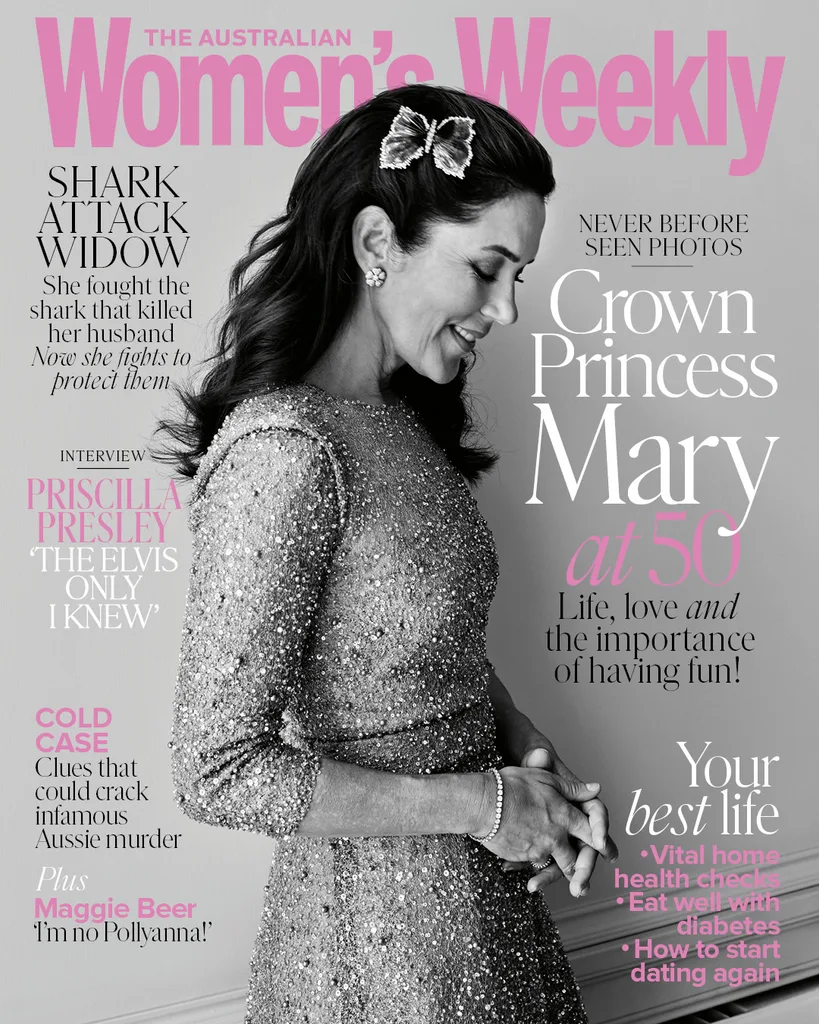

You can read Karen’s story and many others in the February issue of The Australian Women’s Weekly – on sale now.