Merryn Apma-Daley, 60, from Noosa, Qld, shares her story with Take 5.

As the train pulled into Melbourne’s Flinders Street Station, I held my baby Tamara tightly.

“Let’s do this,” I said, stepping onto the platform.

It was 1980 and at 17 years old I was about to meet my birth mother for the first time.

Growing up, I’d never understood why my parents were white while I had a much darker colour.

When I got older, I started asking questions.

“You were adopted at birth,” my mum told me.

I learned that my biological mother had given birth to me in Murray Bridge, SA, and my parents adopted me via a religious group the day I was born.

I had so many questions.

Why were so many of the Indigenous kids I knew adopted into white families?

Why was I taken from my biological mother in the first place?

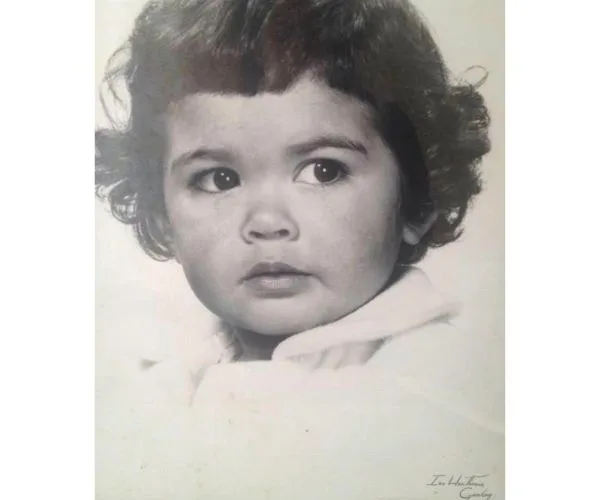

Merryn as a child.

(Image: supplied)Through a pastor, I was able to get her name and arrange a meeting.

Stepping off the train a week later, a group of women stared at me excitedly.

“Are you Margret?” I asked the woman I suspected to be my mother.

“Yes,” she beamed, tears streaming down her face.

She’d brought all five of my aunties with her to meet me.

It was overwhelming but I couldn’t be happier.

“I remember giving birth like it was yesterday,” she recalled.

Margret, 37, told me how she was raped by a white man and had fallen pregnant with me.

At that time, having a child out of wedlock was very taboo.

“I didn’t get to see you before they whisked you away,” she trembled. “It broke my heart.”

Merryn was reunited with her family after 17 years.

(Image: supplied)Taking it all in was overwhelming.

As a mother myself, I couldn’t imagine how painful that would have been for her.

I learned that my family were from Western Arrernte Country near Alice Springs, NT, and that I had two sisters and a brother.

Margret and I stayed in contact, which was fantastic because I had so many questions about my background.

Soon after, I had my second daughter, Candice, and felt comforted knowing that I had reconnected with my own biological family so my children could know their whole history.

When Margret moved to Adelaide a few months later, she introduced me to her own mother, Undalia, who was also known as Minnie Sweet to those close to her.

She told me stories of growing up in Western Arrernte Country.

“I have walked all over this country,” she said, as I listened, enthralled.

Five years after I first met my nanna, she passed away at 89 and I took my first trip to Arrernte Country for her funeral with my daughters.

Stepping off the train, my breath was taken away.

Merryn found art therapeutic.

(Image: supplied)I felt an immediate spiritual connection to the landscape surrounding me.

Back home, I was restless.

“I think I have to go back to Arrernte to be with my people,” I told friends.

Returning three months later with my girls, I got to know more of my family and my background.

Turned out my nanna was a cousin of the landscape painter, Albert Namatjira.

During my trip I watched as the local women drew the landscape in front of me.

“That’s stunning,” I marvelled as they painted dots across the canvas.

Strolling around Alice Springs later that day, it suddenly occurred to me that my people were artists.

I’m meant to be one too, I realised.

I started to paint as a hobby for the first time and found it incredibly therapeutic.

Merryn loves designing fabrics.

(Image: supplied)Using the dot technique made me feel connected to my ancestors.

And while I’d learnt so much about my history, it still felt like there were missing pieces.

In 1997, all that changed when the Bringing Them Home national report came out which outlined how Indigenous children were forcibly removed from families.

That’s me, I thought.

What’s more, it happened to my mum, too. Reading the report unsettled me.

My two daughters Tamara, 17, and Candice, 16, were my rock and painting became my healing tool for the traumas of my past.

I’d envisage I was back in the desert surrounded by my people and entering a dream-like state.

Hours would pass as I sat in front of the canvas, painting like I was in a trance.

Through connecting with other survivors of the stolen generation, I met and married a man named Glen.

In 2012, we settled in Tilba, NSW, together and three years later I opened my own gallery.

When my friend, footballer Michael Long, asked if I’d be interested in painting art to go on the Essendon football jumper for the annual Dreamtime at the ‘G game, I leapt at the chance.

Merryn with her daughter Tamara and granddaughter Yalanda.

(Image: supplied)“It would be my honour,” I said.

Seeing my work on the jersey lit a fire in me to have my art on more fabrics.

But a month before the game, Glen passed away at age 54 from cancer after 14 years together.

His passing took a toll on me and I was too heartbroken to continue living and working in the area, so I shut the gallery and moved interstate, trying not to let the grief consume me.

Two years later, an old friend, Garry, got in touch with me. We got chatting and later fell in love.

When I was settled in Noosa, I knew I wanted to get my business back on track.

Unsure where to turn, I reached out to Sharon Harris, a consultant at APM, an employment services provider, for support in taking a business course.

I learned how to build a business plan, manage my bookkeeping, deal with customers and so much more.

Now, I am a confident businesswoman. And through my art, I feel like I am leaving behind a legacy for my children and seven grandchildren.

When the grandkids come over, they watch me paint and if they are interested, I teach them my style.

So much of Indigenous history has been lost or erased, and as a proud Western Arrernte woman, nothing is more important to me than keeping my story alive.