“If you don’t have the surgery, you’ll have cervical cancer within five years,” the doctor told me.

“Having high-grade pre-cancerous cells means that your chance of not being able to carry a child to full time has risen to 10% and this surgery won’t change that,” he continued.

“But, there’s a chance it will come back.”

“Each time you have the surgery, that percentage rises and as a young Sydney woman, I’m guessing you’re not planning on having a child anytime soon?”

I silently shook my head.

“So, what do you want to do?”

The thought that anyone would say no to surgery when the alternative was cervical cancer blew my mind.

“Let’s get cutting.”

When I’d had my (admittedly pretty late) first Pap smear at 21 I wasn’t worried at all.

I had regular periods and didn’t have any pain or irregular bleeding – the only reason I got one was because I finally had a female doctor so it wouldn’t feel as awkward, and she told me everything looked fine.

When she called me a week later, I thought it was about the chlamydia test I’d gotten for kicks while she was down there and thought my boyfriend had some explaining to do.

She told me I had some abnormal cells in my cervix, which didn’t sound that concerning, but she sounded really sympathetic and then asked me to come in for a chat – so I obviously instantly freaked out.

Not being from Sydney, the referral to Chris O’Brien’s Lifehouse meant nothing to me. It wasn’t until I was surrounded by brochures on how to deal with cancer that it started to click what abnormal cells meant.

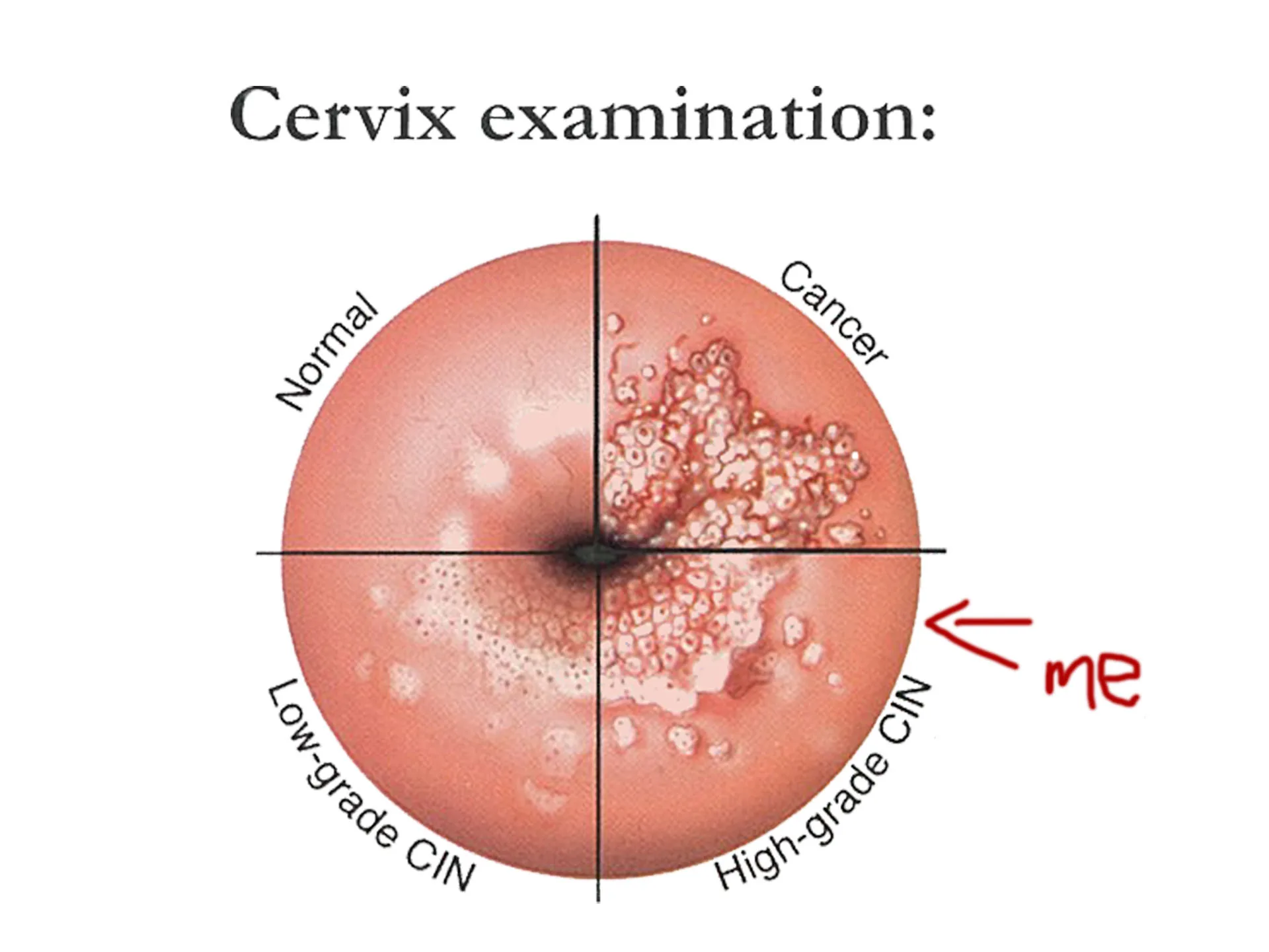

“You have HPV,” the gynaeoncologist told me (see how much that looks like gynaecologist? All the cancer references really went over my head.)

“But don’t worry; for the majority of people, the body’s defences are enough to clear up the virus and this will probably sort itself out.”

In fact, the Department of Health estimates that up to four out of five Australians will have an HPV infection at some point in their lives, and due to the asymptomatic nature of the virus, many never even know.

Mine, however, didn’t sort itself out, and after some fake negatives I was being told cervical cancer was on the horizon at 21.

Looks like a really bad cold sore

As of December 1st this year, there will be drastic changes to the current Pap smears.

The current two yearly Pap smear will change to a five yearly HPV test. This is because while pap smears detect abnormal cell changes, the new test detects the presence of viral DNA at the molecular level, which is the cause of almost all cervical cancers.

The new test undeniably has a lot of benefits, including its superiority at detecting HPV related cancers.

“There are 2 main types of HPV related cancer – squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma,” explains Dr Jane Williams, researcher at the Centre for Values, Ethics, and the Law in Medicine at the University of Sydney. “Paps are more effective at picking up the former but not great on the latter. HPV testing is more likely to pick up both.”

Pre-cancerous cells are ridiculously common

When I discussed having pre-cancerous cells, I was amazed at how many of my friends, peers and colleagues had experienced the same thing – it was overwhelmingly common. That’s why when I saw the age for the new HPV test had been raised to 25, I was horrified.

If I’d waited until I was 25 to have the test, I could already have cancer.

But that’s where Dr Williams, and a lot of other medical professionals, disagree. She thinks the term ‘pre-cancer’ is both inaccurate and counter-productive.

“Most detected abnormalities would never have turned into cancer – and I think that word is a big part of why women think having their abnormal cells removed at 21 has saved their lives,” she argues.

In fact, a study in the British Journal of Cancer found countries where screening starts at 20 did not have significantly different rates of cervical cancer to those that began screening at 25 and extensive research has proven that the ‘better safe than sorry’ approach of some doctors has resulted in high rates of unnecessary surgery, which has the potential to result in problems with pregnancies.

“Many of those abnormalities [CIN] will regress by themselves without any intervention,” explains Professor Karen Canfell, Director of the Cancer Research Division. “It’s also a very long time period between CIN and the possibility of invasive cancer.”

In fact, it’s about 10 – 15 years on average with only about 25% of high-grade CIN cells going on to form cancer – but that isn’t always the case.

A 25-year-old British woman died earlier this year after being diagnosed with cervical cancer at 21.

However, Amber Rose Cliff’s family says she began exhibiting symptoms at 18 but she was refused screening by her GP numerous times because “she was too young”. The NHS only offers screening to those 25 and over.

“If Amber had a smear test sooner then the cancer might have been caught in time, and we wouldn’t have lost her like this,” her brother said at the time.

However, Australian medical professionals have been careful to stress that a woman presenting symptoms at any age can present at any age to be tested by her GP or gynaecologist.

In the recently released guidelines, exceptions to the age of first screening have been outlined.

“If women started having sex before the age of 14, before they were vaccinated or have been victims of child abuse they may be offered a screening test between 20 and 24 years of age” Dr Deborah Bateson, Medical Director of Family Planning NSW explained.

Regardless of your age, it’s so, so important to know the symptoms of cervical cancer. Know your body so that you’re not relying on facts and figures and you can press your GP when something’s wrong.

The symptoms include:

• Bleeding After Sex

• Heavy or longer periods

• Spotting

• Back Pain

• Foul-Smelling Discharge

• Pain or discomfort in the pelvis or during sex

• Difficulty With Bowel Movements

• Leg Swelling, in conjunction with other symptoms

Another invaluable tool in the fight against cervical cancer is the HPV vaccine.

With its introduction we’ve seen CIN cells almost halved in 20-24 year old women, who were the first vaccinated, proving how important the vaccine is.

But some children are missing out on the vaccination. This might be simply because the permission slip never made it home and of course there are the normal, completely unfounded reasons anti-vaxxers have dreamed up, but there’s another frankly terrifying reason as well.

“Some parents may not want their child to be vaccinated because of misplaced fears that the vaccine may encourage early sexual activity,” explains Dr Bateson.

I don’t want to alarm you, but teenagers are going to have sex. And they’re going to be far more scared of falling pregnant or contracting herpes than they’ll be about cancer. The vaccine works best before exposure to HPV and younger people create more antibodies to it than those in their late teens, so your child isn’t going to be able to get it later when you think they’re more emotionally mature.

And HPV doesn’t only affect females – persistent infection can also cause penile and anal cancers in men. The vaccine also protects against 90% of genital warts in both sexes, so don’t exclude your son from the vaccine.

Talk, listen, teach

Look, I would consider myself to be pretty switched on in the sexual health department – shout out to my mum’s sex-ed talks at the dinner table from when I was about seven – but I had no idea that a Pap smear was a cancer screening test until I was sitting in an oncology clinic, and I know most of my friends were the same. Talk to your kids, your friends – spread awareness.

Until the HPV screening comes in, continue to see your doctor for your two-yearly Pap smear. Then, women within the age bracket will be invited to the new screening program and begin the five-yearly tests.

I know cervical cancer is far from the most prevalent cause of deaths in Australia. Last year, about 250 females died from cervical cancer – a number which has been pretty consistent since the comparative data begins in 2006 – and that only counts for 1.2% of all female deaths by cancer that year.

But if any of your mums, sisters, aunts or friends are even one of those 250, then it doesn’t matter how low that percentage is – it’s still too high.

Know your body and stay safe, queens.