Before he plunged into the cold, dirty water that had filled the now-infamous Tham Luang cave, Australian anaesthetist Richard “Harry” Harris could think of 100 reasons why the rescue mission he was about to embark on wasn’t going to work.

The kids could drown, he says, counting them off.

“The mask would fill with water or they’d drown in their own saliva, or they’d die of cold. They were very thin and the wetsuits didn’t fit them property. There was nothing good about it.”

Yet the Wild Boars soccer team and their devoted coach Ekkapol “Ek” Chantawong had already defied the odds, surviving for nine days on nothing but water and prayers inside a cave with dwindling oxygen.

Around them flood waters were rising and receding, a constant reminder that Thailand’s tempestuous weather threatened everything. Monsoon season was upon them, and if the rains started, they would be fatal.

South Australian of the Year, Dr Richard Harris. (Image: Supplied)

“That’s the only reason I was able to do it and to continue,” Harry says.

“I thought: This is the only chance these kids have got of surviving, so if I haven’t got the guts to do it, I’m walking away and basically leaving these kids to die.”

For almost three weeks, the world held its breath as news trickled out of a tiny mountain town in Thailand where the 13 souls were trapped. From late June, thousands of people from all over the world had flocked to the Chiang Rai Province to pitch in with the rescue effort, but it was a doctor from South Australia with an unusual hobby whose calm pragmatism achieved a miracle.

Harry became an instant hero when he delivered all 13 members of the Wild Boars safely home to their loved ones, but the notoriety that has come with it doesn’t sit comfortably.

There are two reasons for this: One, he was simply doing his duty, and though he held grave fears for the boys, he never feared for his own safety.

“I couldn’t not do it,” he says. Second, he simply did not believe the plan would succeed.

Workers begin their rescue efforts to free the trapped soccer team. (Image: Getty)

A week earlier, the father of three had been watching the news coverage from his home in Adelaide, wondering if the rescuers could use his help. A keen diver from the age of 15, Harry had an interest and, in his words, “some expertise”, in cave rescues.

He was in contact with two cave diving friends, one of whom, Rick Stanton, had discovered the team huddling on a sand bank in the ninth chamber of the Tham Luang cave a few days earlier.

“They were painting a pretty grim picture about the conditions in the cave and how dangerous it was,” Harry says.

The water was high and fast-flowing. “It was dangerous and essentially impenetrable to the divers.” Far from being deterred, Harry made an offer.

“I said, ‘If you think a doctor could be of use, I’m happy to come over.'”

Rick asked if it would be possible to sedate the children to bring them out.

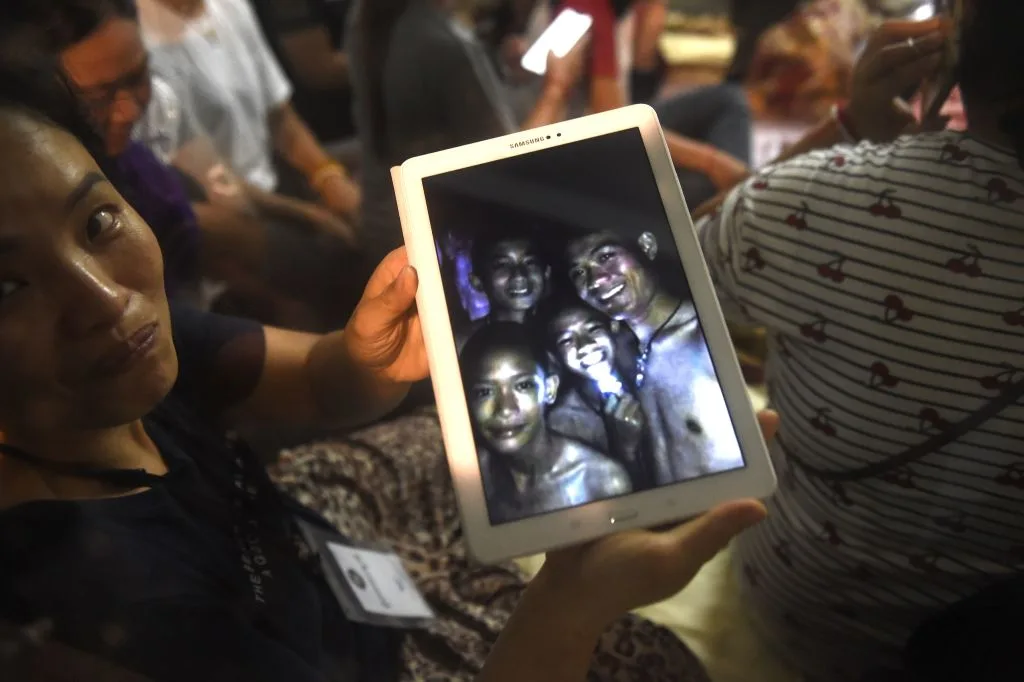

The boys inside the cave during their ordeal. (Image: Getty)

“I said, ‘Absolutely under no circumstances could you safely anaesthetise somebody and then put them under water’.” But Harry wanted to help where he could, so he said farewell to his wife Fiona, his kids and their two dogs Rubie and Alfie and boarded a plane to Thailand.

With him was his dive buddy and fellow member of the adventure-seeking group, the Wet Mules, Craig Challen.

As Harry tells it, there was never any question as to whether they would go to the aid of the imperilled soccer team.

The two men shared the qualities of their beloved Wet Mules: stubbornness, strong backs and “understanding what we enjoy … caves!” But as they traversed the treacherous cave that wound deep into the belly of the mountain, Harry was filled with a growing sense of dread.

“Each time you’d go through some difficult section you’d think: How am I going to bring a kid out through here?”

Dr Harris had enormous doubt upon entering the mission. (Image: Getty)

The plan to sedate the starved boys remained, in his view, impossible.

As he broke the surface of the water at Nern Nom Sao and waved his light around, he was greeted by a rousing sight: 13 grinning faces were clamouring to welcome him.

“They were all pretty excited and babbling and smiling and saying, ‘hello, hello’,” Harry says. “It was a pretty joyous occasion and exciting to see the boys.”

One of the Thai divers who was with them, army doctor Pak Loharnshoon, said their morale was good and that coach Ek had done an amazing job helping them remain calm with meditation. If the boys were scared they didn’t show it.

Harry was amazed by how well they looked, but his excitement was tempered by a dark thought in the back of his mind: “These kids aren’t going to get out of here.”

Harry wants to correct the reports that he stayed in the cave until it was time for the last Wild Boar to make his bid for survival.

“I wasn’t quite that heroic,” he says, explaining that he left each evening and returned the following morning. It was always difficult to leave because, if the rain did come, there would be no way back in.

The plan to sedate the boys and escort them out was coming together, but the threat of rain was ever-present. “There was a chance we wouldn’t ever get to try (the plan) because if it rained at night again, it would be game over,” he says.

The rain wasn’t the only thing that scared him. For the rescue operation to work, Harry had to administer a sedative and then hold the boys under water to make sure they could breathe in their face masks.

“I was pretty frightened actually with that first kid and the first anaesthetic,” he says.

Emergency workers bring in supplies to assist with the mission.

“I’d never administered the drugs in the way we were giving them.”

He wondered: “How long would it take to work? How long would it last? When you pushed that little boy’s head under water, waiting for the bubbles to start appearing from the mask then lifting his head up to see if the mask was filling with water, it was a pretty tense time.”

But the bubbles did appear. One by one the boys were carefully couriered through the sumps and crevices, and word came through they were making it out alive. The mission was succeeding, but there was no time to enjoy it.

“Even on the last day I was still waiting for disaster to occur,” Harry says.

When it was his turn to guide one of the unconscious players through the cave, his fears were almost realised. “I lost the line at one stage and had difficulty finding my way out,” he says.

It was a scare, and a potentially dangerous moment. But as we all know, the last lost boy emerged, safe and well, in the arms of the man who made it all possible.

The boys during their first press release after leaving the cave. (Image: Getty)

For the ordeal to end in triumph was more than anyone had dared hope for but all Harry felt was exhaustion. Even now, the enormity of what the mission achieved still hasn’t sunk in.

“One day leads into another,” he says. “Life has changed around me but I don’t think I’m any different. I’m a pretty pragmatic person, just trying to get on with life.

Harry loves to shoot film footage of the Wet Mules’ cave exploration, and has appeared in documentaries, but this enthusiasm should not be confused with fame-seeking.

“I’m not quite sure how comfortable I feel with it all,” he says. He would prefer to return to his private life. Still, the success was “pretty special”.

“Craig and I have had a few moments reflecting together where we sort of look at each other and have a bit of a smile and think: that’s pretty cool, isn’t it? That’s not a bad job.”