My stomach twisted with excitement as I took the letter out of the envelope.

After two months of waiting, I’d finally received a response.

Dear Miss Finlayson, it read. Let me thank you for your kind and warm letter. I was very moved about the impression Anne’s diary made on you. It gives me great satisfaction that you feel so close to her and will always keep her in your mind.

It was 1956, and I had just finished reading The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank.

Her candid account of WWII and her family’s attempt to hide from the Gestapo was overwhelming. How could this have happened? I kept thinking.

Uppermost in my thoughts was Otto, Anne’s father, who was the only member of his family to survive the Holocaust.

I knew I had to get in contact with him, so I wrote to all the publishers of Anne’s diary until someone gave me his address in Switzerland.

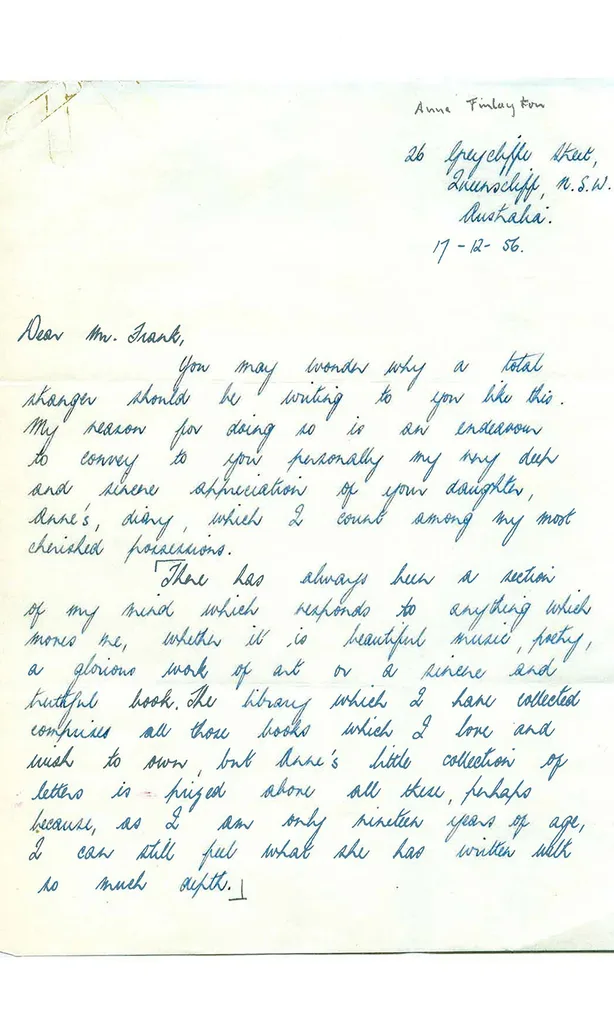

Dear Mr Frank, I wrote. You may wonder why a total stranger should be writing to you like this. My reason is to convey my deep and sincere appreciation of your daughter’s diary, which I count among my most cherished possessions.

Anne’s first letter to Otto from 1956

Now he’d written back.

He thought my letter was moving and was glad his daughter could live on through her diary. He even said he wanted to meet me!

But I was looking after my widowed mother and couldn’t leave her to go to Europe. So I turned down his invitation and we continued writing to each other when we could. He sent me a beautiful English copy of Anne’s diary and I sent him a book I thought he’d enjoy.

Otto started to open up about his experiences. He told me that before they were betrayed, his family had agreed to meet in Amsterdam at a friend’s house if they were captured and separated.

As soon as Otto was freed from the concentration camp, he went to Amsterdam to find his wife, Edith, and daughters, Margot and Anne. He visited the post office each week and asked whether anyone had seen them. But each week he got no response.

It wasn’t until seven years later that he met a man who told him he had seen Anne and Margot in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. Finally, Otto had closure.

But he never got their bodies back. He told me that when the British forces liberated the camp there were too many corpses, riddled with typhus, to deal with. The soldiers had to bulldoze the bodies into big pits in the ground. That’s what happened to his family.

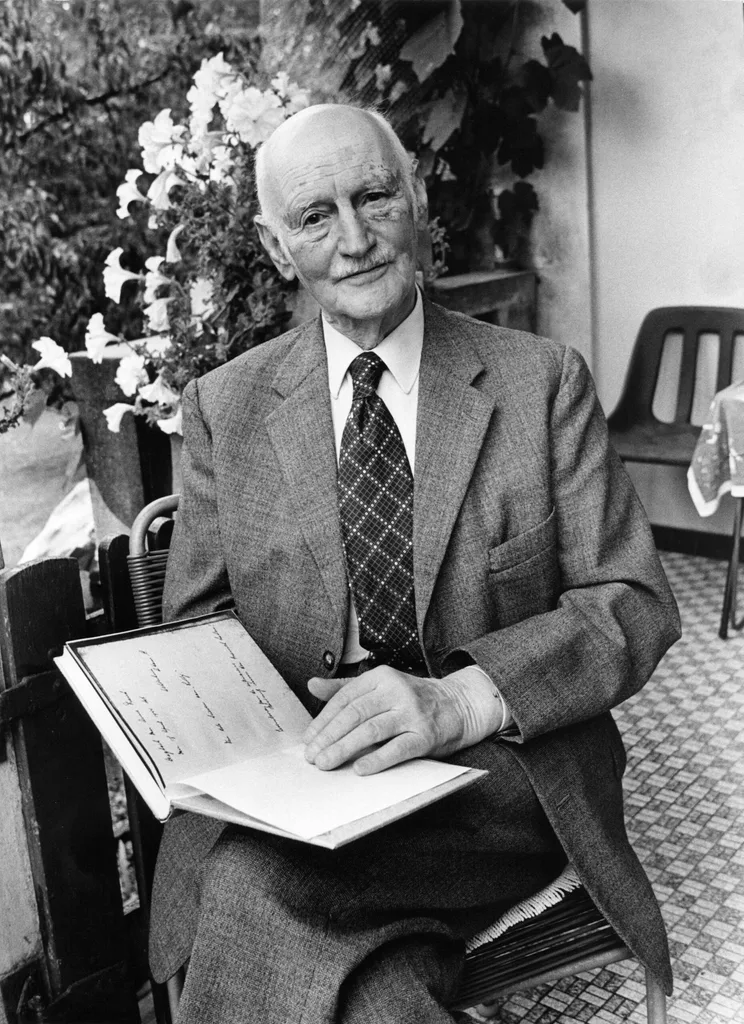

Otto with Anne and Margo

I think Otto needed to clear his soul of the horror he’d seen and he needed to clear it with someone who hadn’t been through it. I was a source of comfort to him in that way.

Anne treasures the friendship she shared with Otto

But it wasn’t until 1976, when my mother died from stomach cancer, that I was able to visit Otto in person.

By then he was living in Switzerland with his second wife, Fritzi. She had also lost her family, except for one daughter, during WWII.

He arranged for me to stay at a nearby hotel. After I had settled in, the phone in my room rang. It was reception, saying there was an elderly man waiting downstairs for me.

My heart pounded as I got in the lift. Otto and I had been dear friends for 20 years now, but I had no idea what he’d be like in person.

When the lift doors opened, he was standing right there.

“Mr Frank?” I asked.

“Finally, Anne,” he said, smiling.

It was stiflingly hot so we hopped on a tram to his house.

“My wife has apple and pear juice waiting for us,” Otto said. “We can sit in my study and talk all day.”

We’d been together all of five minutes when suddenly he turned to me and said, “Do you ever get the feeling you’ve known someone, even though you met them minutes before? Well, that’s how I feel with you.”

I grinned. I felt exactly the same – it was as if we’d known each other our whole lives.

That night, Otto and Fritzi took me to a restaurant next to the Rhine. Otto pointed to the river and joked, “It flows to Germany, so we’re happy to be on the Swiss side!”

Even with all the pain he’d been through, he still knew how to see the light side of life.

Otto Frank

After I left Switzerland, we continued to write letters. I became dear friends with Fritzi as well and we all visited each other when we could.

Then, in 1980, at the age of 91, Otto wrote to me and told me he was feeling poorly and not very energetic.

I hope you can make me feel better, he wrote.

A few days later, as I was writing my reply to him, I received another letter from Fritzi.

Otto has died, she wrote simply.

I was devastated and knew I’d miss my lifelong friend, but I was happy he’d ended up living a long and fruitful life.

I continued to see Fritzi up until her death in 1998.

Anne with Otto’s second wife, Fritzi

Her daughter, Eva, knowing how close we were, wrote to me as soon as it happened.

Mother has died, she said. Now she’s resting peacefully beside her beloved Otto.

I still write to Eva even though both Otto and Fritzi have left me.

I’m still horrified by the brutality they went through and I still question how anyone could commit such terrible acts. But I was blessed to know Otto and Fritzi and I know they felt blessed to know me.