For Sarah McFadyen, the realisation that her five-year-old daughter was actually her five-year-old son came all too publicly, in the girl’s dress aisle of a department store in suburban Melbourne.

“I turned a corner and saw all these beautiful little girl dresses hanging in a row, gorgeous little Collette Dinnigan dresses that took my breath away,” recalls Sarah, 32.

“And in that same moment, I saw what my future was really going to be like. I would never be the mother of the bride. I would never walk my daughter down the aisle at her wedding. I would never be the favourite grandmother.

“All I ever wanted was a little girl. I had my heart set on having a little girl who I could have afternoon tea parties with, who would dress up in pretty little dresses. Instead, my daughter wanted to be my son, to dress like a boy, to have a penis.

“Until then, I’d lived in a little bubble of denial for so long and, in that moment, among all those beautiful dresses, the bubble came crashing down. I put my head in my hands and cried.”

Sarah, a nurse, and her husband, Shaun, a radiographer, are just two of hundreds, perhaps thousands, of couples across Australia struggling with the most confronting and difficult issue a parent may ever face: when their child insists that they are living in the wrong body and they want to change their sex.

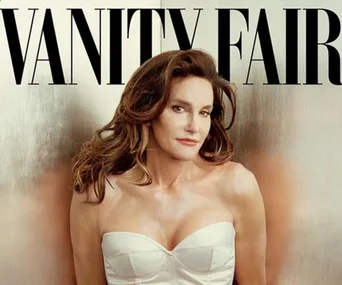

Caitlyn Jenner’s public transformation from superstar sportsman to woman has placed transgender issues firmly on the social agenda. Yet the plight faced by transgender children and their parents is something that is rarely examined in public.

Nobody knows how many transgender children there are in Australia. The very best guess, based on studies conducted in New Zealand, is somewhere between 1.5 to 3 per cent of school-aged children.

Certainly, these children number in the hundreds, but because these are only those in treatment and this is such a delicate and secretive issue, the real number may be much higher.

What is certain is, for some, switching gender at such a young age is both a desire and a necessity. While most “gender dysphoria” children are unable to adequately express their confusion about their gender until they are teenagers, others know that nature dealt them the wrong cards almost from the moment they can speak.

Such was the case for Lyla McFadyen, Sarah and Shaun’s daughter. Lyla now lives and identifies as Jack McFadyen, and has done so since March this year. Yet Jack’s story goes back to when he first began to communicate with his parents.

“I knew about transgender people and what that meant,” says Sarah, “but I never for a moment thought that would ever apply to my child. But by the time he was two, Jack was already showing signs that he didn’t identify as a girl. At the time, it didn’t seem like that. We made up all sorts of excuses for his behaviour, trying to explain all the little things that didn’t fit.”

Jack never liked dresses. If Sarah wanted to put him in one, she’d have to let him wear pants underneath. Initially, she thought it was a sensory issue, that he simply didn’t like his legs being bare.

“I never thought for a moment that it was a gender issue,” says Sarah, who has now gotten used to referring to Jack as a “he”.

“He would never wear headbands or anything girly. He would rip them off. Even when he was six months old, he hated it. The toys he gravitated to were always typical boys’ toys – [Toy Story’s] Buzz Lightyear and Woody were his favourites.

“But, again, we didn’t really think anything about that because there are plenty of little girls who play with boys’ toys. It doesn’t have to mean anything.”

Yet as Jack grew, his preferences became clearer. Action figures won out over Barbie dolls. Boys’ Lego kits were better than girls’ kits because they were boring. And, when he was two and a half, toilet training became an issue.

“He would only toilet- train if he got boys’ underpants,” says Shaun, also 32.

“If we got him girls’ undies, then he would wet himself or he would take them off, or he would poo in them because he knew that we’d have to throw them away. Then, out of desperation, Sarah bought him a packet of boys’ undies and, suddenly, he was toilet-trained. He hasn’t had an accident since that day.”

Even so, Sarah says both she and Shaun were still in the dark.

“I blamed the underwear manufacturers because they didn’t make girls’ underwear with Woody and Buzz on them,” she says.

“I was really angry about that. I guess I was in denial. It was everybody else’s fault, not mine. And certainly not Jack’s.”

When Sarah and Shaun married in 2010, Jack attended as Lyla, in a dress. “That is the last photograph we have of him in a dress,” says Sarah.

“Even then, it took a lot of fighting to get him to wear it. I still have that dress hidden in our home. He found it a little while ago and he threw it in the bin. He has seen photographs of him in the dress and he knows that it belongs to him, but he doesn’t like it. When he threw it out, I salvaged it and put it in a box. He doesn’t know I still have it. I’ve kept all his pretty dresses.”

Not long after, Jack began asking questions his parents didn’t expect. Jack had noticed the physical differences between boys and girls. “He would ask, ‘Where is my penis?’ and ‘When will I get my penis?’,” says Sarah.

“I’d tell him, ‘You’re a little girl. You don’t have a penis. You have a vagina.’ He’d get upset and say, ‘No, I want a penis!’”

Sarah says she and Shaun rationalised as best they could.

“We just told ourselves that he wanted to be like his dad,” says Sarah.

“He was our only child. We didn’t have anything to compare him to. I was a bit of a tomboy, to a point, when I was little. But even so, I was nothing like Jack.

“The thing was, everyone in our life was saying it will pass. It’s just a phase. Don’t worry about it. She’ll get over it. But he didn’t. I used to shower with him at night and, one night, he looked at me and my body and said, ‘Mummy, I hate your body’. I asked why and he said, ‘I don’t want to grow up and get boobies. I don’t want to. I don’t want to grow up and look like you.’ He said he wanted a penis and when I said he couldn’t have one, he cried.”

A week later, Jack tried to remove the outer parts of his female genitalia with a pair of safety scissors.

“There was a little blood, but not much damage. Even so, I was shocked,” says Sarah.

“It was a three-year-old’s response to something he didn’t like. How many children have cut their own hair because they didn’t like it? It’s not like an adult, there’s not the same sort of rationalisation going on. The answer is simple: if you don’t like it, get rid of it.

“I sat down with him and asked why he would do that and he said, ‘Mummy, I don’t want to grow up if I have to be like this. I don’t want to be a girl. I want to be your son. I am your son.”

Sarah didn’t know how to respond. She took him to a paediatrician, but the response was that he was too young to know what he wanted.

“I was terrified,” she says.

“I didn’t know what was going on. It seemed as though everyone was dismissing our concerns. They all thought it would pass, but I knew it was much more serious than that. A phase is a short period of time about particular preferences. It is not a person persistently saying they want another body. This was clearly different.”

Around this time, Sarah decided Jack was probably gay and simply confused because of that.

“In a way, it was kind of a relief,” she says, “because the alternative was something we didn’t want to think about. He would always play with the boys and try to kiss the girls. Being gay made sense. In a child’s mind, it would make sense that if you like girls then you have to be a boy.”

She sat down with Jack and explained that sometimes girls like girls and boys like boys, and that’s okay.

“But even as I was saying this, I was thinking, ‘Please be gay, it will all be so much simpler for you if you are gay.’ Jack looked up at me and said, ‘No, Mummy. I like girls, but that’s because I am a boy and I’m going to marry a girl.’ ”

Starting school was traumatic for Jack. His confusion about his place in the world only became greater as he mixed and played with a broader range of children, all of whom seemed different to him.

“Jack had stopped vocalising about his gender and withdrawn into himself,” says Sarah. “He was very reserved, almost on the verge of depression, I would say. He had friends, but it was hard for him. The really tough part was the toilets.

“We didn’t know about this for more than a year, but he would wait for the bell to ring and when everyone lined up, he would dash for the boys’ toilets when he knew no one else would be there.

“He’d tried to go to the boys’ toilets before, but they would tell him to leave. Then he’d go to the girls’ toilets and girls who didn’t know him would tell him to leave because he looked like a boy.

“There was a point where he was holding out all day and wetting himself because he didn’t know which toilet to go to. We found out that when he went into the toilet, he pulled up his feet so no one would know he was in the cubicle, but one day he overbalanced and fell in. He was stuck for five minutes before someone came along to help. When I heard that, I cried.”

At home, his behaviour became even more concerning. He would stand in the bath and pee because that’s how boys do it. He sat backwards on the toilet because it made him feel like a boy.

If Sarah mentioned his birth name – Lyla – Jack would say, “That’s not me. That’s my sister.”

“It was distressing, not just for him, but for us, too,” says Sarah.

“He was obviously in complete turmoil about who he was. We decided that perhaps the best thing we could do was allow him to use a boy’s name.”

That was easier said than done. Sarah’s emotional commitment had been to a daughter. To actually accept her daughter as her son was far more difficult than she ever imagined.

“Sarah had a much more difficult time with it than I did,” says Shaun.

“It had come to a stage where it just seemed to make sense to let him use a boy’s name. In our minds, it would cause less distress and maybe even create a greater sense of himself. But it took some time before Sarah could actually let go.”

“One parent usually gets there faster than the other,” says Sarah.

“In our case, it was Shaun, not me. He said, ‘We have to do something about this.’ He was much more comfortable with it than I was. I was still fighting it, still clinging to the blind hope that it was really some kind of phase, even though I knew deep down that it wasn’t.”

It all reached a climax at a family function at which Sarah knew Jack would be expected to wear a dress. She took him shopping to children’s outfitter Pumpkin Patch, where she literally begged him to wear a dress.

“If he didn’t wear a dress, then I knew I’d get grief because of it,” Sarah says.

“I spent an hour with him in the store. I begged, I yelled, I negotiated. I even threw my own tantrum. And, finally, he agreed to wear one. I was so relieved. I even thought, maybe this is all going to be okay. Maybe he’s not different.

“But during the trip to the function, he was crying, saying that he hated the way he looked, saying he hated dresses, asking to change. Finally, I had to promise that he could wear his Superman undies under the dress and that he could change as soon as the function was over. I had to change him in the car, but he was crying hysterically. I just thought, ‘What have I done? I’ve traumatised him and for what?’”

The next day, Sarah broke down in the department store aisle.

“I went past the Collette Dinnigan dresses and I lost it,” she says.

“The poor staff had to console me. They had to help me out of the store. But I was finally ready – I had to be.”

They told their daughter he could pick a new boy’s name. He dithered and changed his mind, and finally Sarah said, ‘Right, from now on your name is Jack’. At first, it was only in private.

For the rest of the family, he was still Lyla.

“That was my biggest mistake,” says Sarah.

“I was telling him that he had to be ashamed of who he really was. That was wrong. He was ready, but we weren’t. But I quickly realised just what a mistake that was.

“The instant we started calling him Jack, he changed. Not just a little, but dramatically. He went from being an introspective, quiet little girl, to a loud, adventurous, confident little boy.”

A friend, who has known Jack since birth, came forward a few days later with a revelation.

“She said that she thought Jack was transgender,” says Sarah.

“My mouth must have dropped open because she told me to close it. For so long that had been the unspoken thought in my mind, the one thing I didn’t want to consider. But she was right. I had to consider it. She brought some literature for me and told me to read it. It fitted Jack right down to the ground.”

She also recommended that Sarah and Shaun contact the Melbourne Royal Children’s Hospital Gender Dysphoria Service, the only gender treatment centre for children in the country.

Jack has been in transition since March. That means that he lives and dresses as Jack at all times, at home and at school. Sarah and Shaun told the school what they were doing and contacted the parents of Jack’s classmates so that they knew what was happening and why.

“I said that I would answer any of their questions as long as it wasn’t coming from a bad or hurtful place,” says Sarah.

“Two mothers I spoke to broke down in tears and when I asked why, they said they were thinking about their own children. Some were wonderful. Others simply said okay. One woman said Jack was an abomination and that he would go to hell.”

Jack had a birthday party a few months ago. He invited children from school. Most were happy to accept. One child said he would throw the invitation in the bin because his parents thought Jack was a freak.

Sarah says she knows that she doesn’t necessarily have to worry about how other children will treat Jack, but rather how adults will treat him.

“People don’t understand, I get that,” says Sarah.

“There are people in our family that don’t understand either. They are waiting for more evidence. But there is no magic test that explains this. It’s not hormonal. It’s not a genetic abnormality. Nobody knows what causes it. It just is.

“People say that it’s my fault – I put the idea into his head. I wanted a boy. I let him watch the wrong movies. I’m not strict enough with him. None of that is true. We made a decision based on what we genuinely believe is the best for our child and his future. Thirty per cent of transgender children attempt suicide by the time they are 18. What am I supposed to do, let him kill himself? Would that be enough evidence?”

Today, Jack is under the care of a psychiatrist at the Gender Dysphoria Service. Sarah and Shaun closely monitor their son’s emotional state. This will continue for the next few years until he is about to reach puberty.

“Jack knows that he can change back at any time he wants,” says Sarah.

“We’ve told him that. It does happen, but the percentage is very low. People ask me what will you do if he wants to change back. My answer is that he will change back. It’s that simple.”

Puberty, however, will present special problems for Jack. Transgender children are usually stopped from reaching puberty with drug therapy. It prevents the development of other physical characteristics which will affect the children in the future – breasts in girls and muscle and hair growth in boys.

Yet the biggest problem for Jack will be that if he never reaches puberty, then he can never produce eggs and have a biological child of his own.

“I will explain that to him when the time comes, but how much of that a nine- or 10-year-old will take in is anybody’s guess,” says Sarah.

“My greatest fear is that he will come to me when he is 24 and say that he hates us because he can’t have children of his own. But what choice do I have? I can’t let him become a statistic.

“I love my son for who he is. No conditions, no ifs or buts. I will do everything in my power to help and nurture him so that he can become a happy, healthy balanced member of society.

“If he gets to 18 and hasn’t tried to kill himself, hasn’t abused drugs or alcohol, has developed respectful relationships with people he loves and is a decent student, then I think I will have done my job.

“That is what a parent does for their child. People may not agree with me and I am prepared for that. They don’t have to agree with me because Jack is not their son.

“People look at the outward appearance, but that’s not everything there is to know about a person. You have to look at what’s inside, too. Right now, I have a son called Jack who says he is a boy on the inside. He knows he is a boy and that’s good enough for me.”

This article originally appeared in The Australian Women’s Weekly.