Mark’s non-cricket loving friends could spend an hour this summer watching cricket and also learn something about Mark.

I could talk all day about Mark but today I’m just going to tell one story. The story of Mark’s last few days when he came home to die.

Why is it worth telling?

Because in some remarkable way Mark managed to live out his final days in a way which encapsulated something of his heart, his spirit and essential self. These are the big questions.

When you have the kind of commitment to life Mark had, how do you die?

How do you let go of all the things you’ve cherished with such ferocity?

With a body as broken as Mark’s was, when the news was always bad, how do you reconcile yourself to that brokenness?

And as I was privileged to witness his “demise” as he put it to me so lightly, it kept occurring to me that this is a story he’s never been able to tell anybody.

Mark was a fantastic storyteller and conversationalist. He could always sum up things in a way which was very engaging. I can honestly say without exception I always looked forward to seeing him. I know everybody who knew him felt the same way. He was ridiculously good company. Insightful. Enjoyed everything. Thought about everything.

So how to begin this story?

Mark was in the palliative care section of the Austin hospital and had decided to come home. He was determined to come home to die, a sad situation. We were in the ambulance, I was in the front, Mark was in the back on a gurney, very unwell, and as we started to drive back to the Dandenongs I heard this voice coming from the back, of course it was Mark’s voice.

“Could somebody put the cricket on please?”

It might have had something to do with both the ambos being English but we ride home listening to Michael Clarke pummelling the poms. It was an hour of bliss, a kind of cricket radio bliss, which all the cricket lovers will understand.

Mark chose to die at home with his family amidst the chaos and the beauty and the weather and the community he had come to love.

The moment we arrived home Mark’s spirits soared. You could feel the weight lifting off his shoulders as he arrived at the threshold of the house.

“I’m here. I’m here in the place I want to be.” It was typical Mark. From then on it was a kind of inspired chaos, very sad, moving and also very profound, to be around Mark in the last five days of his life.

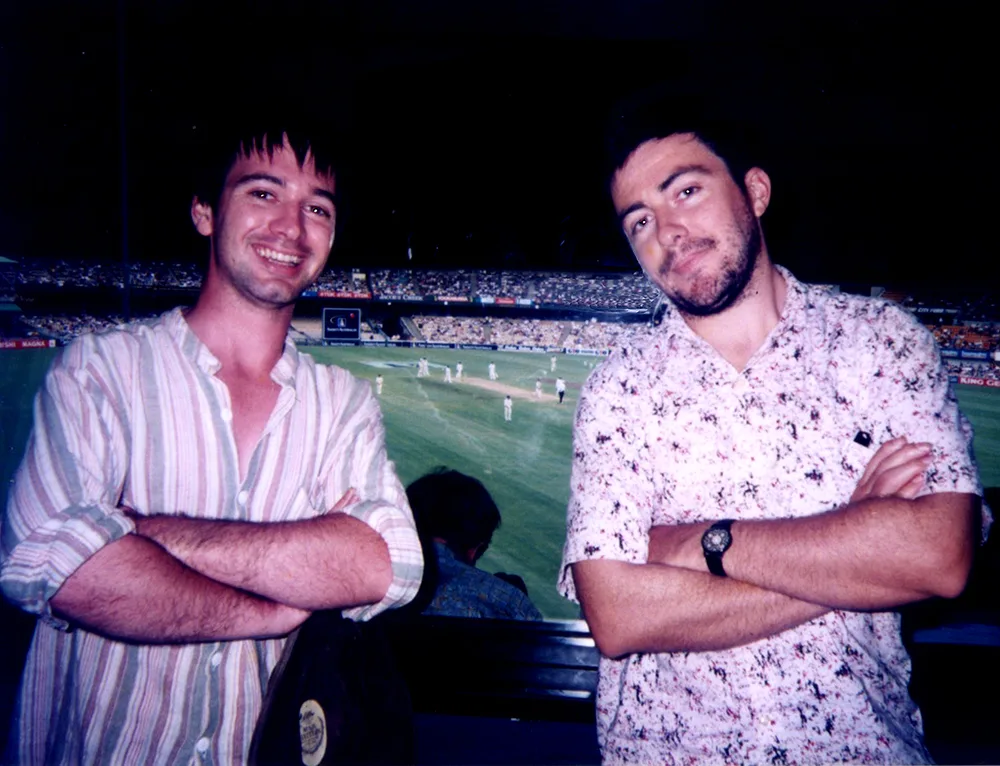

Mark and Damien Broomhead at the cricket in the early 2000s.

Mark in a nutshell? Everything going at once. That whirlwind that Mark and his wife, Belinda, had always had running through the house; an energy, people dropping in and out, the kids running around, it was madness, but it was a good madness.

So what did we do in that time?

We watched much of the 2nd test victory. He gave his usual incisive running commentary. You see Mark loved cricket, the first thing I remember about Mark was the day he was born, my father came into my room and said “Damien, you’ve got someone to play cricket with now.”

And that was Mark from the beginning and I put him through the kind of vigorous training only an older brother could dream up.

One morning I came into his room, Mark very sick, but he pulled himself up on the bed and looked at me. I was expecting him to say something profound but instead he asked “How’s the cricket going?” and wanted a rundown on what was happening.

He sat out on the deck in his gorgeous garden and felt the sun on his face. He listened to music. The weather was that crazy Melbourne weather; four seasons in one day.

For once, with Mark not having long to live, four seasons in one day seemed to serve a purpose. He could experience it all. The sun, the rain, the wind, and the mist.

He nibbled on tiny morsels of delicious food. He sipped lemonade. He talked with a steady stream of loved ones. He demonstrated a fierce and protective love for his wife of 18 years, Belinda. They celebrated their wedding anniversary. He adored his children again and again.

Mark, the runner with the strong legs, had lost his ability to walk but he could hear the lonesome Puffing Billy whistle blowing through the valley reminding him of the race he loved so much. It amazed me that my brother lived in one of the few places in the world where you can still hear a lonesome whistle blowing. Somehow it seemed to me that he managed to attract all this deep soul around him.

We wheeled him into his kitchen where he loved to make a mess. What a fantastic cyclonic cook he could be. He sat, he listened, and he watched.

And every night he smoked a big fat joint and we talked. And what struck me most about those precious evening conversations was how proud Mark was. The best kind of pride. He was incredibly proud of his children. He was proud of his achievements. He was proud he’d reached a position of respect in his career.

He was proud of his old band, ‘The Dreaming Genies’, the music he’d made and the fun he’d had. He gave me all these slightly odd examples. He was proud that in his student days he was a top waiter at the Lobby restaurant in Canberra and could carry ten full plates at a time, and fed Laurie Oakes, who no doubt ate them all. And he insisted “I could still do it now… I could still do it now”. I almost went to the kitchen and got some plates just to watch him do it.

He was proud of the great friends he had. He owned it all, all these disparate elements that he managed to draw around him. And it seemed to me that this was especially important to him.

What Mark was saying was “I am a man in my prime, I own my life and all I’ve done”.

And, as he had done through the entire dreadful illness, he stood tall as if to say, “even though I am frightened, I will own this illness, this experience, too.”

He asserted who he was in the best kind of way.

Early Wednesday his hold on life was weakening. My sister knocked on my door and said “You have to come. The nurse says Mark’s reached a stage of ‘terminal restlessness’”.

I thought, “What, he’s getting better?”

So I went and stood next to Mark’s bed and started watching. Mark was semi-conscious and he wasn’t able to do anything anymore. And what I saw over that day as I came in and out of his room was an extraordinary will to live. All day long family, friends, loved ones and community members came to say goodbye. Mark could no longer speak and his breathing was fitful. He had prayers said over him, songs sung, goodbyes made.

And everyone, including me, was telling him out of love and compassion “let go, Mark”, “It’s okay, you can go now”.

But Mark didn’t, he stayed, last man at the party.

It was almost exasperating. I said goodbye to him about four times. I was so spent I needed a beer.

Despite having been given all the drugs the nurses had left, Mark kept living. After spending several hours with him, my parents left. As Mum kissed him goodbye he broke into the biggest smile of the day, a huge grin, and that was one of the most beautiful things that happened that day.

And at 6pm he opened his eyes and became lucid for the first time since the morning. And when his son, Nic, played him one of his favourite Bon Ivor songs it was as if he came swimming up from some deep, deep place and started to talk.

He said, “Fantastic… More, more.”

That alone was good enough but then, most extraordinarily for me he said: “What a day!”

What a day.

And it hit me like the proverbial diamond bullet between the eyes. Mark had been totally present in that experience all day. And everybody had been telling him what to do, to let go, and Mark actually had other ideas.

He was a fiercely independent soul, a man who would not be told by anyone what to do. So I found myself standing in front of Mark saying in my best older brother voice “I’m sorry I didn’t realise. No Mark you don’t have to let go, stay as long as you want and I’ll play you some songs.”

So we played some songs for him, pulling them off the internet as we went along.

First ‘Message in a Bottle’ by The Police, a song he loved when he was eight or nine years old. It was the first song he loved, he told me that.

‘Walking on the Moon’ also by The Police.

‘You ain’t Going Nowhere’ by The Byrds. He liked to play it at the odd social gathering.

Then Lou Reed, maybe appropriate given the amount of morphine Mark had in his system.

‘Perfect day’; a beautiful son.

Then ‘I’m so free’, which starts off “Yes I am Mother Nature’s son and I’m the only one. I do what I want and I want what I see…”

Then at sunset, during the Velvet Underground’s astonishing ‘I’m set free’, and as I held his lovely hand for the last time, Mark breathed one last shallow breath and it was over. And I thought, yes Mark, you’ve made your point. Your terms.

Mark had reached some kind of awful limit of suffering and yet he seemed to be saying in his death “I am still here, I am witness to this. I love and enjoy life and I want more life. That is who I am.”

In the end we are human and we do these things.

And I felt this is what he was asserting; I am not a child, I am a man, I am a father and husband, I have achieved much, I am proud of who I am and I love myself dearly.

You see, the most extraordinary thing of all, when Mark received his bad news, that the cancer had returned, we met up and Mark told me something that stunned me.

He said to me that he didn’t feel loveable. Not loved, loveable.

I said to him, “Mark, everybody loves you. You are loved. And he said, “No Damien that’s not it, I don’t feel loveable.”

And what I feel strongly enough to tell you is that in that last short period of his life, my deeply sensitive, kind brother, Mark, finally, suffering but always present, always himself, somehow managed to love himself fully and without qualification.

And there lay the extraordinary power of his passing and the greatness of the man.

So where is Mark now?

Some say it’s soul that leaves the body but I like to think that it’s the other way around. The body is going but the soul resides still in the hearts and minds and memory of those who loved Mark.

In particular, times infinity, Mark’s soul with its immense wisdom rests at ease in the gorgeous hearts of his and Belinda’s four children, where he has enfolded it over time with such love and attention and grace.

So Nic, Noah, Michael and Sophia, when life throws up its challenges, as it will, and you do what can or must be done, don’t forget, if you’re struggling you can still, always, go ask your father. Because he’s there in your heart waiting for you.

So here’s to Mark. He loved it all.