Since becoming a free woman in June 2023, Kathleen Folbigg has been busy enjoying the simple pleasures of life.

The 57-year-old has moved into her own home, bought a car, learned how to change a tyre for the first time and adopted a white whippet-cross rescue dog, Snowie.

“She saved me, I saved her,” Kathleen told the Sydney Morning Herald.

“She offers unconditional love. But there are no strings. It’s pure.”

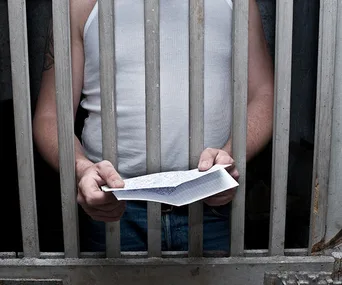

BEHIND BARS

Once branded Australia’s worst serial killer, Kathleen was convicted of killing her four infant children, Caleb, Patrick, Sarah and Laura.

In October 2003, Kathleen was sentenced to 40 years in prison with a non-parole period of 30 years, which was reduced to 25 years after a successful appeal in February 2005.

A petition signed by more than 100 scientists insisted there were medical explanations for the deaths of her children.

It’s now known two of her children had a genetic mutation that led to their deaths.

In July this year, her lawyer Rhanee Rego applied on behalf of Kathleen to receive an ex-gratia payment to compensate her for spending a third of her life behind bars.

It’s expected this payment will be the largest compensation payout in Australian history, eclipsing the $1.3 million payment to Lindy and Michael Chamberlain in 1992.

A spokesperson for the NSW Attorney General, Michael Daley, and Premier, Chris Minns, says the application, which includes a 300-page account of Kathleen’s time in prison, is being carefully considered.

MPs are pushing for this payment to be hurried up.

Kathleen says this is not about “wanting money for the sake of money” and that once paid, she’ll donate some to genetic research, animal welfare groups and to funding additional transition centres for women leaving prison.

She’ll also use some of the money to buy a home and a “playmate” to keep Snowie company.

RECLAIMING LIFE

“I like the idea of being able to go to a rescue place because to me that’s pretty much like doggie jails,” she explained.

“They spend too long in there and sometimes some of them don’t ever get to come back out. It’s a dismal end for some.”

Kathleen still doesn’t know where her children’s ashes are, believing they have been “scattered somewhere”.

“I’ve had to sideline and put to bed the whole business of where my children’s ashes are,” she explained.

She is now putting her energy into reclaiming her own life.

“I want the people who helped me through this to get on with their lives and stop worrying about me,” she says.