Jodi Rowley clambers through the damp, dense jungle of Cat Tien National Park in south Vietnam. It’s winter 2007 and all over the park, animals are under threat.

A race is on to identify species. Jodi, a herpetologist (or amphibian biologist), walks quietly through the night, listening for frog calls and peering into shadows, when, in the torchlight, she spots one of the prettiest creatures she’s ever seen – luminous green, with perfect round toe pads and webbed feet, staring at her with huge black and yellow eyes.

“She was gorgeous,” Jodi, now 37, recalls. “I knew she was a flying frog but I thought she was a more common species, the Black-webbed Flying Frog. It wasn’t until a year later, when I saw one in the wild, that I thought, ‘Wait a minute, if this is a Black-webbed Flying Frog, what was that?'”

Jodi and her team had discovered a new species and it couldn’t have come at a more fortuitous time. Jodi was in need of good news. Just months before, her mother, Helen, had been diagnosed with ovarian cancer and was struggling through treatment. As a tribute to her, Jodi named the new species Helen’s Flying Frog (Rhacophorus helenae).

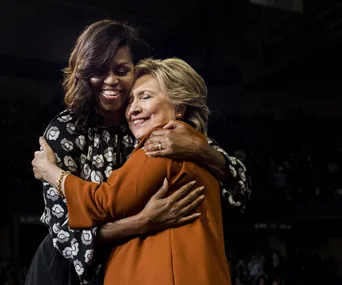

Jodi and her mum, Helen, after whom she named a new species of flying frog.

Ten years later, Jodi and Helen have brought half a dozen frogs to hop through the greenery at The Australian Women’s Weekly photo studio.

Helen, who is facing the possibility of more treatments in coming months, is energetic, petite, graceful – and can’t contain her enthusiasm for Jodi’s work.

“Have you seen my frog?” she asks, and whips out a picture of her namesake printed on a bright green tote bag.

“I’m incredibly proud of Jodi. She’s devoted to these frogs.”

Jodi, Curator of Amphibian and Reptile Conservation Biology at the Australian Museum, has discovered or co-discovered 25 new species and confesses her life revolves around frogs: “I’m obsessed with how vulnerable and gorgeous they are, how adaptable, how you can find them everywhere from deserts to rainforests, how many different variations they have of doing things – some build nests, some glide with their hands – frog diversity is insane. We know so little about them. I love them even more because they’re in so much trouble.”

Frogs are among the most endangered animals on the planet. As a result of habitat loss, predators, pollution, disease and climate change, 42 per cent of amphibian species are currently threatened with extinction. Herpetologists are under mounting pressure to identify species before they disappear and to learn enough about them to reverse their decline.

One of the problems they face is that frogs live in diverse and far-flung environments and there aren’t enough herpetologists to cover the ground. That’s why Jodi’s team at the Australian Museum has developed a free phone app, called FrogID.

It enables users to record frog calls on their phones and send their data back to the museum, vastly increasing scientists’ knowledge of the habitats of species.

“It’s Australia’s first national frog count,” says Jodi. “All around the country, people are recording frog calls with a smartphone. If you hear a frog in your backyard, while you’re camping or on your commute, you click record, get 20 seconds of the frog calling and submit it. The app will try to match it to a species on the spot. Then it will send the call to the Australian Museum with your GPS location and the time you recorded it. We receive it, verify whether it’s that species or not, and you’ll get notified what frog you’ve found.”

As we go to press, 34,000 people have downloaded the app and the museum has received more than 15,500 recordings, with new calls coming in from around the country every day. To keep up with the workload, Jodi has taken to sitting on the bus with headphones on, identifying frogs on her daily commute.

“It rained in Alice Springs a couple of weeks ago and we got recordings of frogs rarely heard by scientists because they’d have to be in the desert on the day it poured – the next night, those frogs are gone,” Jodi says.

“This app has incredible potential. We could discover new species and populations of endangered species we don’t know are there, and it’s important to collect recordings of suburban frogs as well. We need this information now so we can identify how many species we have in Australia, where they’re distributed, which need assistance and what we can do to help them bounce back. We can give frogs a chance at survival but we have to act now. The first step is to find out as much as we can about them, and people are happy to help us because they care about frogs.”

Jodi was a city kid. She loved animals but wasn’t outdoorsy. Her fascination with frogs began when she was studying environmental science at university.

On her first field trips she waded at night through streams and mosquito-infested swamps, and she says, “I completely fell in love with frogs”.

Jodi’s partner is a graphic artist, Chad, who hails from Texas. He sometimes travels with Jodi on field trips and has learnt more about drawing frogs than he’d imagined possible. “He perhaps doesn’t like wading in ponds as much as I do,” she laughs, and he occasionally chides her for caring more about frogs than him, but mostly he’s encouraging.

“He understands I’m excited by what I do and believe in what I do. It’s important,” Jodi explains, “because sadly we know what happens in environments where frogs have disappeared. This has happened in places like Panama in Central America, where there are only a handful of species left.”

Without tadpoles to eat the algae, streams clog up. Frogs are “protein packages” for predators and without them other species starve. Frogs help reduce pests around crops. Tadpoles compete with mosquito larvae and eat mosquito eggs, so diminishing frog populations have implications for the spread of diseases like malaria and dengue fever. “Then there are the chemicals frogs produce that scientists are beginning to discover – anti-virals, anti-microbials, glues to be used in surgery. Every time a species disappears, we lose a resource,” says Jodi. “That’s why frog conservation is such a big part of my life. I’m trying to make sure these surreal, gorgeous creatures stick around.”

To download the free FrogID app, visit australianmuseum.net.au.