The brightest light, shining through the fear and darkness of the COVID-19 pandemic, has been a spontaneous outbreak of gratitude that has encircled the world.

It began, with the virus, in the city of Wuhan, in China, where in mid-January the sound of voices shouting encouragement began to echo in the evenings through empty streets.

The phenomenon spread to Italy where, in typically effusive style, people sang arias and popular songs from their balconies (there was a mighty nationwide rendition of YMCA) and applauded healthcare workers as they passed below.

An evening round of applause for healthcare workers travelled even more swiftly than the virus through the UK and Europe, where the youngest royals led the clapping, then on to Turkey, India, New Zealand, Australia and further.

Children wrote letters and posted heartfelt notes of thanks in windows and on social media pages. Restaurants around the world delivered free meals to healthcare workers.

In return, doctors, nurses and others working on the front line of this crisis posted messages of encouragement to the millions of people all over the world who were making their jobs easier by staying at home.

Here at The Australian Women’s Weekly, we would also like to say thank you, by introducing this small band of heroes who represent so many more.

Mental health guardian: Christine Morgan

Christine Morgan of the National Mental Health Commission has been encouraging all Australians to be #InThisTogether.

(Image: Supplied)CEO of the National Mental Health Commission and National Suicide Prevention Adviser to the Prime Minister

Christine Morgan was a little over a year into her new role as the Prime Minister’s suicide prevention adviser when the landscape changed in a way nobody could have predicted.

Her task had always been immense, but now it affected every single Australian. Fortunately, Christine is an optimist.

“The bushfires and the COVID-19 pandemic are very real opportunities to highlight the fact that our mental health is as integral to us as our physical health,” Christine says.

Australians are resilient, she believes, and hard-wired to help each other out. She has faith that those qualities will get us through the pandemic.

“We can come out the other side with that sense reinforced.”

Christine has always been drawn to working with those in need. When she finished school, though, she opted for law, but after rising through the corporate ranks she took a more junior role at Wesley Mission.

Suddenly she was working with children in foster care, families in distress and people with severe disabilities. She had found her calling.

“I was totally blindsided by one beautiful, beautiful woman in her 40s,” Christine recalls.

She had an intellectual disability and “she had three words in her vocabulary that had to describe her entire existence, and I was just blown away by the people who supported her and took the time to really try to understand what she needed.”

Christine has had many encounters that moved her deeply, and they all shared one quality: courage. During this time, her message is to stay connected and protect your own mental health so you can then help others.

“We can come out of this ‘warfare’ with a real sense of that Aussie willingness to reach out and care for each other,” she says.

#InThisTogether is the National Mental Health Commission’s campaign to support the wellbeing of Australians. Visit their website here.

School superhero: Mechel Poukalis

Mechel Poukalis is principal at Cumberland High School in Sydney, where 70 per cent of students speak a language other than English, and many of who were stranded overseas when travel bans came into effect.

(Image: Supplied)Principal at Cumberland High School

At Cumberland High School, in Sydney, 70 per cent of students speak a language other than English, and 57 different languages are spoken altogether.

When COVID-19 hit with force in February, many of principal Mechel Poukalis’ 780 students were stranded overseas.

Others, whose families had already weathered SARS, were self-isolating, terrified in their homes.

“You can imagine the fear if you’d been through that,” says Mechel. “So we’ve been dealing with this outbreak from early on.”

The school now runs its regular timetable online and the library is open for children who need to be at school. They can join the online classes there, and Mechel is determined to keep that space open for them.

Some wouldn’t have adequate supervision at home, others wouldn’t have access to technology and there are others for whom school is simply a safer space.

Some teachers have always volunteered to come in early to provide a breakfast club, and that’s still running, even with diminished numbers. Plus, as the canteen has closed, Mechel is buying pizzas and other favourite take-aways for lunch.

WATCH BELOW: Prince Harry checks in with parents of his patronage WellChild via video link. Article continues below.

Cumberland’s staff are pulling out all stops to ensure this pandemic deprives no one of an education.

“Our administration team is calling children at home to make sure they’re logged on and know what to do, because we’re running our regular timetable, as we would if the kids were at school. We have learning support available on the phone. We have telecounselling when students need someone to talk to.

“Many of the kids are very distressed. I think they’re missing us immensely, and we’re missing them.”

Mechel has also supplied internet dongles and laptops to kids who need them, boxes of supplies have been ferried home for HSC major works, and she has even ordered groceries for families who have been unable to get to the shops.

“Some of our families have it really hard,” she says. “That’s just the way it is.”

Mechel knew in her heart that she wanted to be a teacher at age four, but it wasn’t until a Year Nine history teacher (shout out to Ms Paraveskis) spotted her talent that she began really dreaming of going on to university. She was the first of her very traditional Greek grandparents’ granddaughters to get there.

Now 48, she is determined to support her teachers and students through this crisis.

“There’s so much negativity and so much despair at the moment,” she says, “but when we come together and support each other, we’re stronger. We will be able to get through this.”

“I believe that, and I try to communicate that to my school community, to say: It will be hard but you can always call on us to be there for you. We will do whatever it takes.”

Giving shelter: Donna Cavanagh

Donna Cavanagh work with domestic violence shelters has become ever more crucial with the advent of social distancing and self-isolation.

(Credit: Photo supplied.)Manager of Women’s Community Shelters’ Sanctuary – Hills Women’s Shelter

Twenty minutes into our interview, domestic violence survivor turned shelter manager Donna Cavanagh sheds some tears for the women she knows are now trapped inside a house with their abusers.

“I knew we were going to need more rooms,” she says.

Donna and her employer, Women’s Community Shelters (WCS), acted quickly when the government started talking about COVID-19 lockdowns, knowing what it meant for vulnerable women.

They tried to create as much space within their existing shelters as possible and support those who were being rehoused with outreach services.

They devised programs for traumatised children who would be stuck inside and sought resources for mothers who were going through the most difficult times of their lives in the middle of a global crisis.

“We’re managing mums with trauma but now they can’t do their normal things, like take the kids to the park or out for an ice-cream,” Donna says.

For all her foresight and tenacity, Donna knows there will be women she can’t help. The lockdown has increased demand for services, and she fears that will only grow as the virus subsides and the restrictions are relaxed. Right now, many women can’t escape.

She describes a woman in the type of situation she sees every day: “I don’t think she’s going to be able to go to Woolworths and have her phone and her children and her plan to flee.”

“It’s going to be happening – guaranteed – the escalation of everything … Mum can’t escape.” She wipes her tears and focuses on what can be done. “Support the people who are behind the closed doors and nobody can see.”

WCS has had a 25-30% increase in demand since March 23. Visit their website here.

Doctor to the rescue: Michael Novy

COVID-19 emergency response training taking place at St Vincent’s Hospital in Sydney.

(Image: Supplied)Senior Staff Specialist in Emergency Medicine, St Vincent’s Hospital, Sydney

Dr Michael Novy has worked at the frontline of emergency medicine for more than 25 years. He flew into the Maldives after the tsunami in 2004 and into Bali after the bombings in 2002.

He was on the team that resuscitated two-year-old Sophie Delizio when a car crashed through her childcare centre in 2003. He has rescued victims from flood and fire and violence across Australia and the Pacific.

Yet asked what single incident has challenged him most, he says: “To be honest, this one.”

“I have a bit of experience in disaster medicine, which is what we’re dealing with at the moment, but in every other situation, I’ve known exactly what to do. In this situation we’re all learning together – as a hospital, as a healthcare system, as a society … We’re all learning on the run.”

The first COVID-19 patients and their families have come through St Vincent’s in recent weeks.

The atmosphere in the hospital, he says, is one of “contained apprehension, but it’s made us focus and to do our job better than we’ve ever done it before.

WATCH BELOW: Carrie Bickmore shares what many parents are experiencing while self-isolation at home with their kids. Story continues after video.

It feels like a tidal wave, and this is the start of it. We’ve seen the water rush out, we’ve had a chance to prepare and now the water is beginning to come back in.”

There’s added stress too, he says, because for the first time in his career, he is dealing with a healthcare emergency that could affect the people he loves.

“My partner Eliot is my rock,” Michael says.

The couple lives not far from the hospital with their bulldog puppies, Puddles and Mr Eaton Waffles. But Michael is most concerned about his parents.

“I’ve stopped seeing them because I want to keep them safe.”

His parents arrived in Australia as refugees from the Czech Republic when Michael, now 51, was mere months old.

His destiny was set, he smiles, with a card he received for his first birthday that read: ‘Now you’re 1 and you’re going to be a doctor.’

Aside from “stay at home”, is there any other advice Michael would like to share?

“Yes,” he says gently. “Be kind to each other.”

“Being nice, being kind to yourself, your friends and family, the people around you, that’s what’s really important. That’s how we get through this together.”

Fast-tracking a vaccine: Christina Henderson

Christina Henderson says “it’s been a wild ride” for her team at the University of Queensland.

(Credit: Photo supplied.)Project Manager, Rapid Response Vaccine Pipeline, the University of Queensland

A tightknit team has worked around the clock at the University of Queensland since January, fast-tracking the development of a vaccine for COVID-19.

“It’s been a rollercoaster,” Project Manager Christina Henderson says.

0“It’s been an immense effort from the entire team – scientists, laboratory assistants, management and support staff, finance and legal teams, technical experts – and our families too, sacrificing family time, sleep, hobbies, downtime.

“We often work from early morning until very late at night, and through the weekends. It’s been hard emotionally, and quite draining, especially now that it’s lasted for months and there are many more months of hard work ahead.

“But this is what we must do to have a shot at halting the spread of the virus.”

A year before COVID-19 broke, CEPI (the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovation) had funded the UQ team to develop its revolutionary new technology, ‘the Molecular Clamp’, which was designed to speed up vaccine development in case of a pandemic.

“But none of us anticipated this day would come so soon,” says Christina.

“In the last few months everyone’s been working in overdrive, trying to complete all phases of vaccine development within unprecedented timelines. It’s been a wild ride.”

As part of that plan they have taken the extraordinary step of beginning mass production of the vaccine candidate while clinical trials are still underway.

It’s a financial risk (made possible by extra funding from the Queensland government) but if it pays off, it will greatly reduce the time between testing and the potential release of a vaccine.

1“It’s been exciting and a little scary, I watch the global numbers rising every day,” says Christina, who took time out last weekend to celebrate her son Robert’s third birthday.

“The biggest stress for me personally is trying to be on top of such a dynamically evolving project. This is far from a typical vaccine project trajectory and is extremely challenging to manage, but it has to happen this way. Taking the traditional route would mean losing valuable time.”

Care in the country: Lynne Lambell

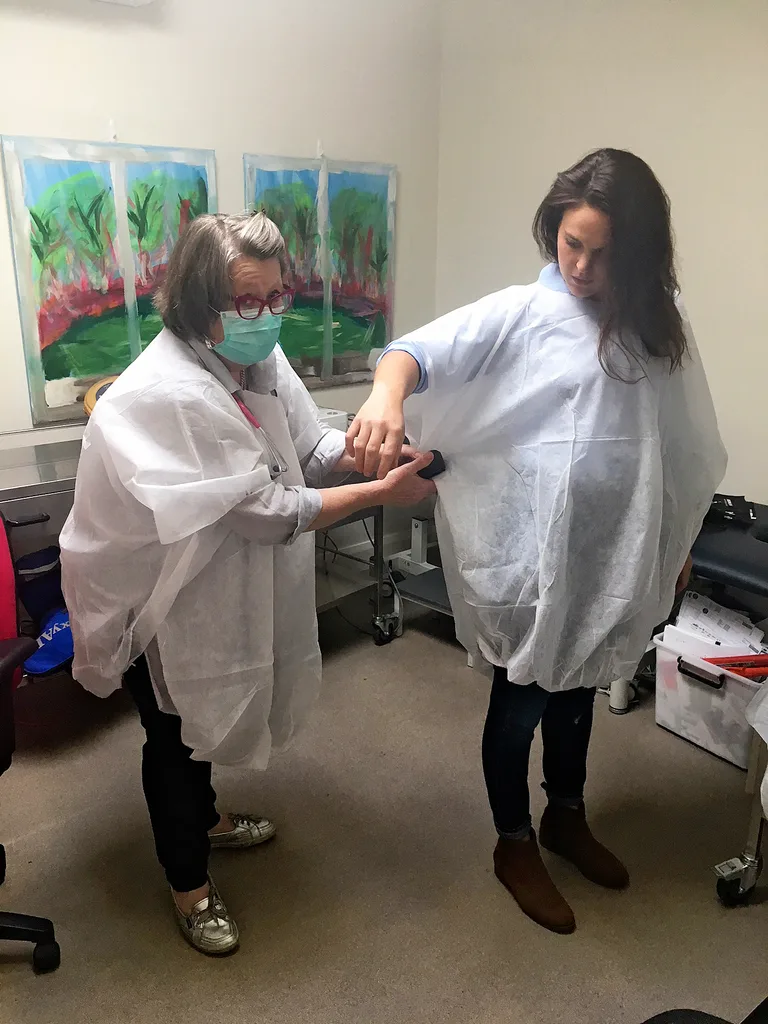

Lynne Lambell and a colleague showing how to improvise on making protective gear.

(Image: Supplied)Practice Nurse and Infectious Control Officer at the Orange Wellness Family Centre

In regional NSW, practice nurse Lynne Lambell is working yet another 12-hour day at the Orange Wellness Family Centre. It’s from this nurse-led, bulk-billing clinic that she is responsible for managing and co-ordinating the medical care of 2000 patients with chronic diseases.

“It’s an enormous load. I feel so responsible for the safety of every single one of our patients, plus our team,” she tells The Weekly, adding that she also has the role of infectious control officer.

“We’ve all been doing training, we’ve been planning, we’ve had meetings over lunchtimes to improve our care. Healthcare workers are used to working under pressure. But this is like waiting for a war.”

The fear of what is to come is a real concern in regional Australia, where resources are sparser than in big cities.

2Lynne is especially worried that, while many of her patients can talk to the team each day via the government’s Telehealth video link and others are able to come to the clinic for urgent treatments, some of the most vulnerable to infection are not in a position to do either.

So Lynne and her small team of part-time nurses have been tasked with continuing home care for those most at need.

“These are the ones we want to keep right away from The Wellness House,” Lynne says.

“So we’re going into their homes, and we’ll get into trouble soon as we’re running out of PPE – personal protective equipment.”

With 45 years of nursing under her belt, however, Lynne is nothing if not resourceful. She’s been creative and has crafted her own personal protective equipment, using some handy materials in order to continue vital care during the pandemic.

“We got some new beds and they sent us all these paper sheets to go with them,” she says, chuckling.

“I’ve saved those and we’ve got staplers so we’re making a little protective apron we can wear when we go out to see our patients so we’re not taking anything to them. It looks very attractive, let me tell you!”

For now, Lynne is doing her best to keep positive and continue in what she calls “the best job in the world”.

3“We are all human,” she says with a shrug.

“We’re all as scared about the coronavirus – none of us is particularly keen to catch it. But the thought of not working hasn’t occurred to me.”

Soup van saviour: Lina Pahor

Lina Pahor is still delivering soup to the needy despite the pandemic’s developing situation.

(Credit: Photo supplied.)President of the St Vincent de Paul Footscray soup van

For 18 years, Lina Pahor has given up her Saturday nights to deliver hot meals and a warm smile to the residents of boarding houses and high-rise commission flats in Melbourne’s western suburbs.

Lately, she’s had to radically rethink how the St Vincent de Paul soup vans can continue to visit those in need.

“Generally, we volunteer and walk away feeling good. With this, you roll up and you think, gosh, we’ve really got to keep people safe,” Lina says. “What we normally do is knock on each door, have a chat and hand over food.”

For many people, she says, “it’s not just about delivering food, but also about human connection. We have a lot of people for whom we are their friends. Our smile might be the only smile they see all week.”

4She fears they are feeling the impacts of the pandemic the most. The soup van that once delivered meals now drops off hampers once a week.

Volunteers drive out in teams of two – sitting apart in the van – and then call to let people know a delivery has been made.

“It’s the easiest way to get as many people fed as safely as possible,” Lina says.

Where she can, she shouts a ‘hello’ through a closed door, standing at a safe distance. The recipients “are so grateful and so nice, and even those who were a bit rough around the edges before are so understanding.”

The new system has its challenges. Many rooming houses don’t have fridges. Some people don’t have pots to heat the soup, or bowls to eat it from.

“On the weekend, I collected as many pots and pans from friends and other places as I could. I just gave them what they needed,” Lina says.

Demand for support has risen, but thanks to the generosity of the community Lina hasn’t had to say no to anybody yet, and is doing everything she can to keep the service running.

“We’re just going from week to week.”

5Need help? Contact the St Vincent de Paul Society on 13 18 12 or visit their website here.

Read more stories of local Aussie heroes in the May issue of The Australian Women’s Weekly, on sale now.

The Australian Women’s Weekly May edition.