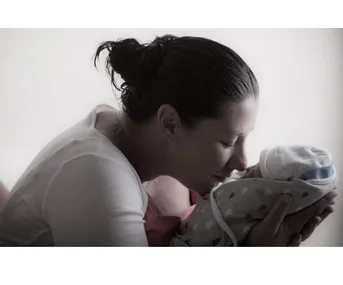

It is a stunning photograph of a mother gazing lovingly at her baby boy. But that didn’t stop Facebook from removing it when someone complained that it was inappropriate. The problem? The peaceful baby in the photo was dead.

The photo was taken by photographer Imelda Bell who works with UK charity Remember my Baby.

“It shows the love that she feels for her son, and is a beautiful moment.

“Someone has reported the image to Facebook as offensive and left [the mother] feeling devastated,” Bell explained on another post.

Bell says that the mother (who prefers to remain anonymous) has the right to be proud of her son and to post photos of him, in the same way that any parent has the right to post photos of their children.

Of course this bereaved mother would much rather be posting images of her son as he grew up, but instead she wanted to share a photo that captured him the way that she wants to remember him.

While we can’t deny that seeing a photograph of a dead baby is uncomfortable and distressing, it is easy to understand the mother’s motives for posting the story. But despite the stats (as many as six babies are stillborn a day) talking about stillbirth and miscarriage is still taboo.

Social Media strategist and author Anna Spargo-Ryan says that although Facebook is changing, people still feel the need to portray a ‘perfect life’.

“We don’t talk about miscarriage in general, and social media reflects that. One in four pregnancies (or higher) ends in miscarriage but there are complex feelings that go with them, including shame and fear,” she says.

Spargo-Ryan also notes that even when it’s locked down, social media can seem quite public and some people might not be comfortable sharing such sad news.

“Miscarriage in particular doesn’t have any outward representation – you don’t have a funeral, there’s no headstone, maybe no one even knew you were pregnant. It’s a quiet kind of grief and maybe talking about it on a public platform doesn’t feel right,” she explains.

When it comes to stillbirth, and in particular sharing stillbirth photos, Spargo-Ryan says that topics such as grief and death are often swept under the carpet in western cultures.

So what can we do to change that? Perhaps the sharing of stillborn photos would be a good start.

Maggie Green* tells me that she would love to post photographs of her stillborn daughter on Facebook. “She was a beautiful baby, and I’d love to be able to show her off in the same way I post photos of my living kids,” she says.

But while Green would like to share the photos she has she is worried that friends and family members would feel uncomfortable. “I don’t want people to see my angle and think ‘oh I don’t need to see that’,” she explains.

I asked Green if posting photos of her daughter would help her grieve. “Yes, definitely. It would make her fleeting life seem more tangible. People could see her and know that while her life was brief, she was a real baby,”

Stillbirth photos or status updates about miscarriage might be uncomfortable. But we need to get used to them. Because making them public will help eliminate the taboo, and make life easier for the thousands parents that just want to talk about their babies.

*Name has been changed