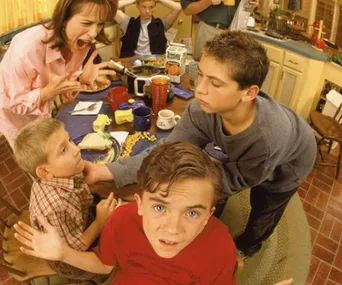

Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, you may think you know what your teenager is doing on their phone, but would you ever think they could be sexting?

While you may not want to believe it, there is a very good chance your teenager may be among the estimated one in seven teens sending sexually explicit texts or the one in four receiving sexts.

New research, published in journal JAMA Pediatrics, has confirmed sexting is on the rise among high school students, calling for better education in schools and in the home. The prevalence of the smartphones and other digital devices is unsurprisingly the cause of the increase sexual behaviour of this kind.

Of the 110,000 teens aged between 12 and 17 recorded, 10 per cent admitted to forwarding a sext without consent.

Parents have been encouraged to discuss sexting, consent and practicing safe digital behaviour with their teenagers. Sexual health expert, Dr Christopher Fisher at La Trobe University’s Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health & Society, says while sexting can be just as an extension of natural sexual curiosity, it’s important for teens to recognise the “permanency” of sending a sext.

“Parents are really important it that conversation. Parents can provide some guidance in terms of values and how they might approach winning in this digital age we are in,” Dr Fisher told AAP.

How do parents start the ‘sext talk’?

Lsyn psychologist Elyse McNeil says when engaging in a conversation about sexting or any sexual activity, parents should remain open and non-judgmental.

“Use a calm, neutral voice, and withhold any negative or critical comments,” she says.

Instead of talking at your teenager about sexting, McNeil suggests approaching the topic with questions to encourage a discussion.

“Ask questions and seek to understand. This reduces feelings of being judged, and will increase the likelihood of your teenager feeling able to talk to you about it,” says McNeil. “Ask your teenager what they know about sexting, if any of their friends do it, if they ever have, and what they think of it.”

As the conversation progresses, McNeil recommends you ask your teenager what issues or challenges they think might arise as a result of sexting. If they say, “I don’t know” prepare yourself to discuss issues like “consent, the permanency of messages and the potential impact on their future, the risks of texts being misconstrued by the other party, and losing control over where their private and personal information may go.”

Of course your teenager may be unwilling to discuss sexting at all with you. In that case McNeil says, “Let them know you recognise there are complex issues they face as a teenager, with social media and other challenges and that you are there to discuss it at any time.”

10% had forwarded a sext without consent

Researchers at the University of Calgary, Canada, conducted an analysis of all the published research literature on sexting, which included 39 international studies between 2009 and 2016.

A total of 110,000 teens aged between 12 and 17 from numerous countries including Australia, were involved in the data.

According to the findings, 15 per cent reported sending a text and 27 per cent had received one.

Frighteningly, an estimated 10 per cent had forwarded a sext without consent or had a sext forwarded without consent.

For more information on teenage sexual health and tips on communicating with teens, visit Better Health Victoria.