As a former occupational therapist, Emma Gee, of Kew in Victoria, thought she knew what was important for her stroke patients.

It wasn’t until she had a stroke herself, at just 24, that she realised she didn’t.

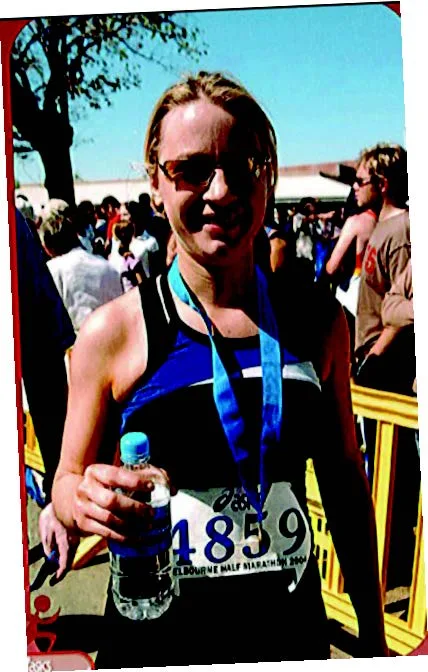

“At 24 I was fit and healthy. I ran half-marathons and climbed Mount Kinabalu in Malaysia. However, everything changed when I went to get a running injury checked out in hospital.

The subsequent investigations discovered an arteriovenous malformation – basically, a tangle of blood vessels – in my brain stem. Doctors thought it may have been precipitated by the altitude and dehydration on my climb.

Surgery was essential, but risky.

Nine days later, I woke from a coma unable to swallow, speak, blink or walk. I had suffered a stroke.

After a spell in Intensive Care, I spent the next eight months in a rehab centre in Melbourne.

As a former therapist, I’d learned to be patient-focused and thought I knew what to expect. However, nothing had prepared me for being so vulnerable and debilitated; it’s not until you’ve been a patient yourself that you discover what really matters.

For instance, all the attention was on my physical progress, but I had emotional issues as well.

I have an identical twin who was a reminder of everything I’d been. I knew I couldn’t return to my old life and could see nothing to go forward to.

I saw a psychologist, but being unable to speak, I could only sit and wonder, “Why am I here? All I can do is listen to her saying she understands.” Still, at least I qualified for rehab.

I knew other young stroke survivors, especially those who didn’t present with my physical deficits, who didn’t qualify for the service.

Also, although rehab was awful, people did expect me to be disabled and gave me the appropriate help. That’s more than I got outside the unit. I encountered daily inappropriate behaviour from the public.

My world was, and is, at a permanent angle. I suffered double vision and had to learn to walk again.

One day, practising my walking up and down my local swimming pool, a woman scolded me for being drunk in the water! Everything in life felt frustrating, but having been stripped of everything I knew, I had no choice but to rebuild myself.

Today, I’ve done that. I learned the art of public speaking and travel all over Australia talking to health professionals about disability and the importance of a holistic approach. I also talk to the general public about resilience.

We can’t always control what happens to us but with resilience, we can control how we deal with it.

THE FACTS

Understanding strokes, who they affect and what to look out for are critically important – and may just save your life or the life of a loved one. Here’s what you need to know.

THE PERSONAL AND ECONOMIC COSTS

According to the National Stroke Foundation (NSF), one in six of us will suffer a stroke in our lifetime.

It is our second biggest killer after heart disease and kills more women than breast cancer and more men than prostate cancer.

Right now, there are 437,000 Australians living with the after-effects and this number is predicted to rise to more than 709,000 by 2032. A massive 65 per cent have such significant disabilities they need assistance to carry out daily living activities.

The personal and economic cost is enormous – around $5 billion a year – yet strokes seem to slip under the radar when it comes to public advocacy, says neurologist and stroke expert Dr Bruce Campbell.

In 1996, the government declared it a “national health priority”, but failed to take any further action. Disturbingly, there are no signs of improvement even now. In fact, dedicated stroke units are being pared back or even abolished, according to the NSF.

INVISIBLE SYMPTOMS

Perhaps that lack of public attention is because stroke symptoms and signs are often “invisible”. Survivors don’t see a stroke coming and then don’t have the energy to battle for support.

It could also be because we think of it as an inevitable part of old age. Yet, as Dr Campbell says, “I’ve currently got two 25-year-olds on my stroke ward.”

That’s not unusual either.

Each year, two children in every 100,000 will have a stroke – from newborns to teenagers.

Dr Campbell, who has a pioneering drive to improve stroke outcomes, believes every survivor should have access to a stroke unit, staffed by an allied health team of specialised doctors, therapists and physios.

However, four in 10 Australians who have a stroke do not receive their care in a dedicated stroke unit

30% suffer post-stroke depression, which is characterised by lethargy, irritability, lowered self-esteem, withdrawal and sleep disturbances.

Last year, about 51,000 Australians suffered a new or recurrent stroke – that is 1000 strokes a week or one stroke every 10 minutes. Only 7 per cent of patients eligible for clot-busting treatment receive it.

UNNECESSARY DEATHS AND DISABILITY

To put it into hard numbers, 12,000 Australians who suffer a stroke each year cannot access basic care, resulting in an additional 700 people dying or being left disabled unnecessarily.

Frustratingly, this can be as a result of the most basic omissions, such as being discharged from hospital without medication to prevent another stroke, or being given food or drink before their swallowing ability is screened, resulting in aspiration or sucking a foreign object into the airways.

Currently, 20 per cent of survivors make a total recovery with no symptoms at all, says Dr Bruce Campbell, with a further 20 per cent having no loss of activity but small side-effects such as numbness or facial asymmetry. These figures could be improved with better after-care.

HOW TO PREVENT A STROKE

Being aware of the risks and pro-active about reducing them is the best way to prevent a stroke.

Two-thirds of Australians have three or more risk factors, with 3.1 million adults over the age of 18 having high blood pressure – the biggest single preventable risk factor for stroke.

“Even young people should be having their blood pressure and cholesterol checked regularly,” says Dr Campbell.

“Know your numbers. Ask what your blood pressure is – don’t just accept someone saying it’s okay. The top number should be less than 140 and the lower the better.”

These factors can also reduce your risk:

• Keep your weight down.

• Quit smoking and reduce alcohol. Regular heavy drinking can raise blood pressure to consistently high levels.

• Exercise more – at least 30 minutes of brisk walking a day – and avoid fatty, processed foods and salt. Those who have a family history of stroke should be particularly vigilant.

Spot the signs immediately

Learn the FAST way to recognise the signs of a stroke.

Face – has the person’s mouth drooped?

Arms – can they lift both arms?

Speech – is their speech slurred and do they understand you?

Time – Time is critical – if you see any of these signs, call triple 000. You need paramedics to get the affected person to hospital and notify specialised medical staff they’re on their way. Clot-busting medicines work best if they’re administered within 90 minutes of the stroke and not longer than four and a half hours.