“I don’t like my breasts as they are so whatever you can do to make them nicer, do it,” says a woman before going under general anaesthetic, laughing about how she may as well get an upgrade to make them “a bit perkier please”.

It’s 2pm at Gosford Private Hospital and so far, it seems like your average day in the life of a plastic surgeon – except this 30-something is suffering from cancer, not vanity.

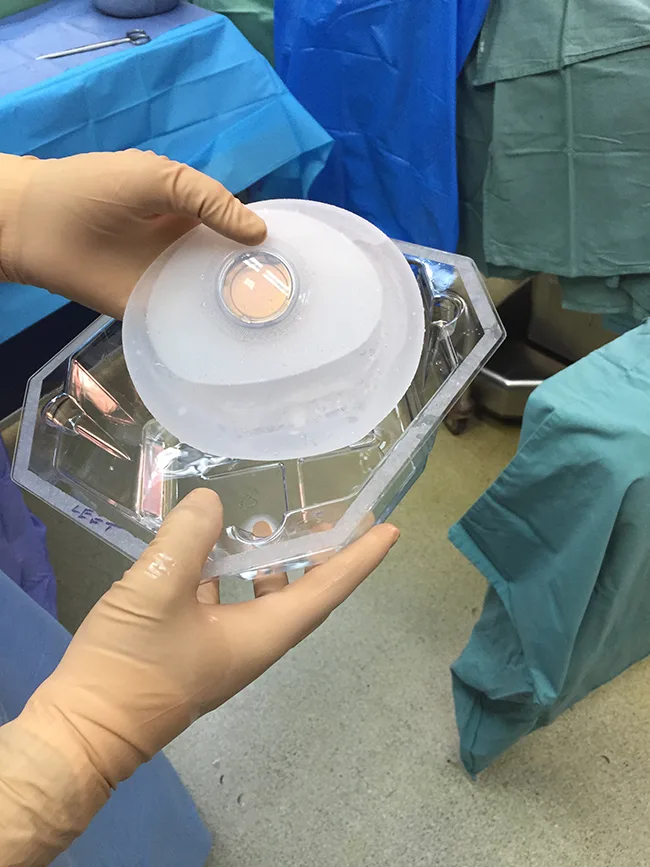

She’s had a double mastectomy and Dr. Gazi is now inserting tissue expanders into the open wounds where her breasts once were in preparation for a reconstruction.

For this woman in particular – and many other breast cancer survivors – the reconstruction is “the final step in getting over cancer,” says Dr. Gazi.

And as this woman’s final step is in full swing, the surgical nurses, the anaesthetist and the surgeons are discussing everything from the obesity crisis to Buddy Franklin’s absence from the AFL field.

Everything from Queen to Mumford & Sons has also been playing in theatre on a Pioneer boom box set up by one of the surgical nurses (aka, DJ Anthony).

Most people think surgery is this serious, tense place, says Dr. Gazi, but it’s just like any other workplace in the end.

And no, there haven’t been any facelifts or nose jobs in this workplace this morning.

While he does have patients – like the fit 75-year-old woman who still rides motorbikes and now wants a facelift – coming in to his consulting room wanting their crow’s feet and laugh lines to disappear, Dr. Gazi also sees patients wanting breast reductions so they don’t have to book into the chiropractor every week.

“I think for us – the line between cosmetic and reconstructive is a bit blurred,” says Dr Gazi in the hospital staff room (and the most important room in the entire building, for caffeine replenishment, of course).

“You don’t ‘have’ to do [the surgeries], but if you can make the patient feel better about themselves, and it’s safe, who’s to say.”

“With modern medicine I think we’re pretty good now at saving and prolonging life and that’s reflected in the fact that we have an ageing population, which forty years ago we didn’t have.

“And if we’re keeping people alive for longer – we need to make sure that we’re giving people the quality of life as opposed to simply allowing them to be on this earth for longer.”

Plastic surgery comes into it when life is expected to be lost, too.

“Sometimes you are operating on these patients to alleviate or reduce their pain so they can die in a slightly more comfortable state.

“You need to do big reconstructive procedures, like the microsurgical transfers; taking flesh from somewhere else and repositioning it into someone’s mouth so they can still swallow. Even though they know they’re going to pass away from their cancer, at least they’re not going to drown in their own saliva.”

Facial paralysis reconstruction is where his passions lie, and last year Dr. Gazi had a 29-year-old patient, Irene Da Costa, who at just two-years-old developed Bells Palsy. She was initially misdiagnosed and missed the key treatment time to prevent the physical impact of the disease, consequently growing up with one side of her face paralysed. With age – and the nature of gravity – the paralysis would only get worse, and could lead to blindness.

“So for her whole life, she had never been able to smile,” says Dr. Gazi.

“I did quite a big operation where we transported muscle out of the leg and then micro-surgically joined that muscle to the blood vessels in her face and also joined nerves to nerves in her face.

“I saw her last week and she came in and she was smiling. And it was emotional because she was actually using it to communicate.

“To see somebody smile who – for her whole life – had never smiled before; that for me was a pretty special moment.”

Dr Gazi Hussain.

*

In 1972 an Indian teacher and his wife left Zambia – where they had lived for almost a decade – for Australia, mainly for their children’s education. They had five children.

Their eldest, who was in year ten at the time, would need to move overseas for university if they remained in Zambia. So in order to “keep their family together” they applied for visas and were accepted to the land Down Under. After a plane trip and a brief stint in Melbourne, they put some roots down in Western Sydney.

“To have Indians in Bankstown at that stage was a real anomaly,” says Dr. Gazi, who is the youngest in that family.

“I have memories of walking on the footpath and cars would slow down to look at us.

And you’re probably thinking the family’s transition Down Under came with blessed relief but “in many respects when they came to Australia it was a harder life for them than they were used to,” says Dr. Gazi now.

“Because in India – and also in Africa – it was quite a standard thing; you would have servants.

“My mum, she hadn’t washed dishes before. As a family, I remember my dad sitting down and talking to us and saying ‘We all have to contribute to running the house’.”

All five children did just that, and all five graduated with university degrees. Two now work in IT, another runs a department for Medicare, another is a lawyer and their youngest, Dr. Gazi Hussain (or Dr. Gazi as he prefers), is a plastic surgeon with a keen interest in facial paralysis reconstruction. He is also a senior lecturer at Macquarie University and the past President of the NSW Branch of the Plastic Surgery Society, and the current Honorary Secretary of the Australian Society of Plastic Surgeons.

So the move was worth it.

*

“Do you want me to get that Gaz?” Asks a man, sitting, legs spread apart, elbows on knees.

It’s 11am (yes, rewind a few hours), we’re back in surgery and a phone is ringing. The index finger of the man sitting is swiping up and up – again and again – against another iPhone 6 as he stares intently at the screen.

“No,” replies Dr Gazi, standing a couple of metres away. He stares just as intently down at the flesh he’s cutting open with a scalpel. Whoever it is, he can call them back.

“Good,” replies the man sitting, “because I’ve got a good score going on here.”

And as the anaesthetist works on his Candy Crush score (or the score on some app of the like), Dr Gazi has a top score of his own to reach. Or a very good score, at least.

But the stakes are a little higher. With each cut and stitch, Dr Gazi gets a little closer to perfecting a woman’s left nipple, which has burst open after she took part in a ‘boxercise’ class a couple of weeks after her breast reconstruction (and double mastectomy prior to that).

Since 9am this morning Dr. Gazi has pinned back a little boy’s ears – he was being called a monkey by his peers at kindergarten – and removed a growth from the arm of a woman in her mid 70’s.

It was caused by a cut when she was trimming the bougainvilleas in her garden, she says, but Dr. Gazi thinks it’s “coincidence” and the growth is most likely a skin cancer.

So he cut out it out, sent it off to the lab for testing, and covered the fleshy wound with a skin graft using “a shaving of skin” scraped from her right upper thigh (by leaving the “dermis” – or the thicker part of the skin underneath – her thigh will heal quickly).

A tissue expander.

*

It’s just past 1pm and Dr Gazi is eating fish and chips. He orders this every second Wednesday when he’s working at Gosford. It’s quick to eat and easy for the staff to order.

He has almost an hour-long lunch break before his next patient is on the table. But this is a rarity. 10 minutes is usually all he gets.

So why this workplace? This career?

“I guess I was attracted to medicine because it was dealing with people,” says Dr. Gazi, who first leant towards medicine in high school. But the closest workplace he could get into for work experience was a nursing home, which he then went on to work part-time at while studying medicine.

“I would talk to the patients in the nursing home and – like anybody – their lives were always fascinating and interesting. And that was one of the things that made me keep doing it as a student.”

That bond is what makes the long days, these days, worthwhile.

“I think there are very few jobs you can say ‘I really, really, really enjoy being at my work far, far more than the days I don’t enjoy being at my work,’” says Dr. Gazi.

“Financially it’s a well-paying job, but it’s really that sense of an achievement and that sense of making a difference in people’s lives that makes it worthwhile.”

*

It’s now 5pm. I’m handing my scrubs in and leaving Dr. Gazi with three more patients – all with skin cancers – to go.

The days in surgery are long days, but between consulting and operating at Gosford Private Hospital and Concord Public Hospital, it seems busy is just a constant for the father of four.

Yes, he’s a family man, too. His wife, Souha, is a lawyer, and currently getting back into the workforce after taking time off to raise their four children. They have two daughters (Sabreen, 16 and Aleeya, 11) and two sons (Adam, 14 and Zayd, 4).

Dr. Gazi’s eyes light up when he talks about them, and when asked whether any of his kids hope to get into medicine he shakes his head with a smile.

“Why didn’t you?” he asks, as I told him my father is a doctor, too.

“Because he was always working.” And Dr. Gazi nods, still smiling.

He’s always made it to his children’s “big moments” but admits the juggle has been hard. Because if your patients need you, you have an obligation to see them. Especially after surgery.

*

A month has passed, and a week ago, I gave Irene Da Costa a call. The woman with the brand-new smile.

She used to work in sales and is a mother of two to a five-year-old boy and three-year-old girl. They are the two people she went into surgery for.

“Kids are the ones who ask questions,” she says, “and now I feel more confident going into the school yard with them.”

It took one year and two surgeries. And when she woke up from the second surgery “I felt like I was being papped” she says, laughing.

Her parents, best friend and husband could all see the new-found symmetry in her face as they stood over her hospital bed, and her dad couldn’t resist taking a few snaps.

Irene had been told she would only be able to smile with clenched teeth. She wouldn’t be able to smile spontaneously with an open mouth. But it was a smile, nevertheless.

“Later, when I walked into [Dr Gazi’s consulting] room he saw me smiling spontaneously, without clenching my teeth,” says Irene.

“He was practically bouncing around the room.. like a kid in a candy store.”

So while she had the newest smile, Dr. Gazi had the biggest. The stakes had been high, and he’d just got a damn good score.

What’s not to smile about?