Nola Duncan’s husband was, by no means, an inattentive man. Every morning, he’d bring his wife coffee in bed – sometimes with a romantic sonnet he’d penned especially for her – and when he’d travel for work, he’d leave her a love note for each day he was away.

Married for 29 years, Nola and Michael Westfield* were kindred spirits who shared a passion for poetry, politics and classical music; they’d often have picnics together by Canberra’s Lake Burley Griffin. It was the second marriage for both of them and Nola thought they had something special. Their friends did, too.

A scientist and senior academic, Michael was widely admired for his wit and intellect, his warmth and generosity. “He was the embodiment,” says Nola, “of everything I thought a man should be.”

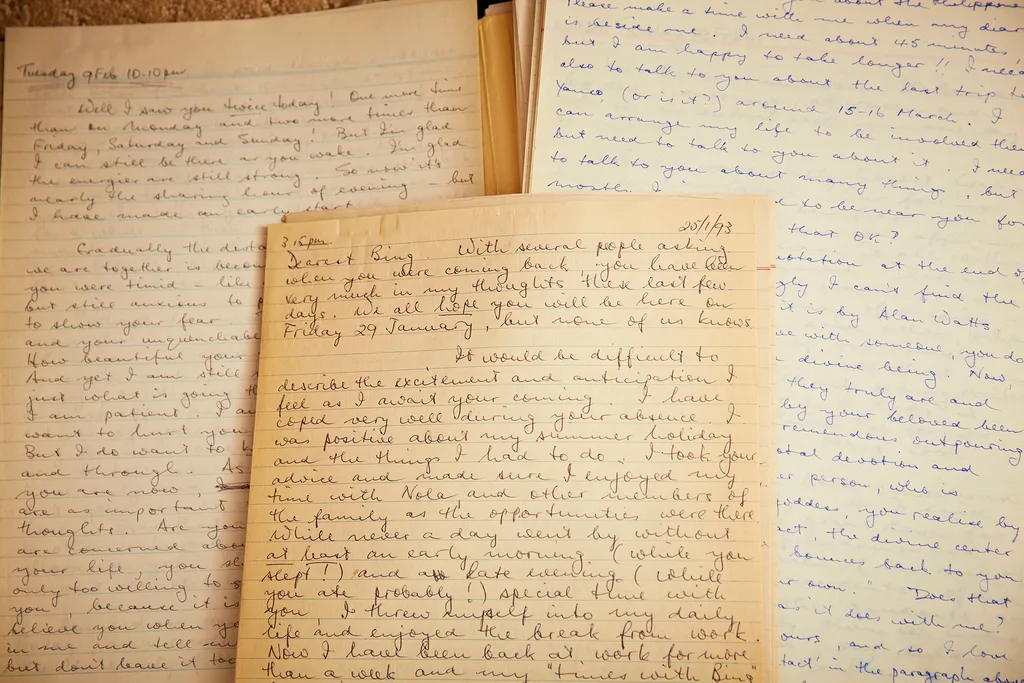

When 76-year-old Michael died of a cardiac arrest three years ago, Nola was devastated. As a new widow, she went through the motions, feeling foreign and listless, but eventually, just after the first anniversary of his death, she felt ready to move on. She decided to clear out his things in the garage and that’s when she found it – a sealed box of letters between Michael and one of his former doctoral students.

“It was surreal,” recalls Nola. “These letters had spilled out. I recognised the writing and there were these endearments, ‘dear, beautiful, most darlingest’, and I’m thinking, what is this? I started reading them and they were erotic – I considered them pornographic.”

There were 741 letters, documenting a six-year love affair that started in 1992 when Michael was 56 and Bea was a 31-year-old married mother of three. It took two weeks, reading day and night, but Nola studied every one of them.

“This was just a man I didn’t know,” she says. “With every letter I read, my memories were sullied.”

Worse than the affair, she says, was the cruelty of his leaving the letters for her to find. The couple had downsized to a townhouse four years before Michael’s death and he had deliberately brought the box with them.

“I don’t believe for a minute that he forgot they were there,” she says. “He wanted me to find them. It speaks volumes about how much the affair meant to him that he could not give those letters up.”

During a two-hour conversation with The Weekly in her immaculate townhouse on Canberra’s suburban outskirts, Nola doesn’t cry, but she often stares into the middle distance, struggling to make sense of her husband’s duplicity. It’s more than two years since she found the letters and she still seems hurt, angry and embittered – as anyone would be, perhaps, if their apparently perfect husband of 30 years betrayed them so spectacularly.

In fact, Nola’s daughter recently threatened to stop visiting her mother if Nola didn’t stop talking about it.

This 72-year-old grandmother may appear quite fragile, but there’s steel there, too. She’s measured and articulate – a woman who knows her own mind.

Six months after she found the letters, she decided to write a book – as a “cathartic experience”, she says. Michael left behind four children and Nola has three – and all but one of them were against the book, The Widow, co-written with Libby Harkness, published by Random House Australia on October 1 – and yet she went ahead anyway.

When we speak, almost no one but the children and her closest friend knows the book is coming – and Bea has no idea either. Nola’s circle is about to learn a whole lot more about Michael. He may have been a literate, erudite man, but his letters are mawkish and over-the-top, proving the young don’t have the monopoly on delusional, embarrassing romances.

Michael and Bea constantly refer to their affair as the “Great Love” (or “GL”) – “a holy love, given to only a very few”, writes Michael, a mystical “mind-marriage”, which is “beyond our human imaginings”. (The pair even conducted a “soul marriage” by the lake using entwined pine needles as wedding rings.)

In his letters, Michael seems manipulative, too, insisting to Bea that the GL can not only co-exist with their marriages, but enhance them. Evident throughout is the reckless self-obsession and addictive melodrama of an adulterous affair.

“Forget my job, my responsibilities, my marriage to Nola – nothing means more to me than your love,” writes Michael. “It consumes and obsesses me.”

As for Nola, “I love her as my life’s companion, my very good friend, the one to share children and grandchildren with, the house-builder and homemaker,” Michael tells Bea. “Our love – yours and mine for each other – is on another plane.”

He also reveals that on the rare occasion he does make love with his wife, “it is more like a kind gesture to a good friend”.

That has to sting.

“Yes, I’m angry at Michael – he didn’t need to do that,” says Nola, but worse than critiquing their sex life was his lie to Bea that he had told Nola about the affair – and that his wife was okay with it.

“He portrays me as a stupid woman, a flaky housewife,” says Nola. “Of course, I didn’t know about it – and I certainly didn’t condone it.”

In The Widow, Nola annotates Michael’s letters, slamming his “sanctimonious bleating” and “odious drivel” and describing her husband as “a predatory, lustful older man”, “petulant child” and “love-struck loon”. Nola says she wrote the book in the (so far fruitless) quest for catharsis; she couldn’t keep the secret to herself and she wanted to head off gossip by setting the record straight.

“I keep it to myself or everyone knows,” she says. “I don’t think there’s any halfway. Not for me.”

Asked if she was motivated by revenge, she seems genuinely shocked at the suggestion.

“How can you have revenge on someone who’s dead?” she asks. By ruining their reputation, I say. “I hadn’t thought about that,” she says. “No, I’ll say no … I don’t think so … I’m not a vengeful person by nature.”

She is clearly rattled, clasping the pendant portrait of her grandmother at her throat. “I don’t want to demonise him and I didn’t think I had,” she says. “The first bit of the book, I’ve written all the good things about him. Everything was positive. It’s only when you get to the letters – and he’s responsible for them.”

Yes, but she is responsible for publishing them. Can she understand why his children would be upset? The letters will be embarrassing for them – and painful. “Well,” she says, “it was painful for me.”

It seems curious, then, that Nola still wears her wedding ring. Taking it off, she says, has never occurred to her. She has excised all of Michael’s pictures and possessions out of her house and yet she wears the most symbolic thing he ever gave her.

It isn’t the only contradiction: Michael’s “morally bankrupt behaviour” left her feeling “demeaned and undignified” – and yet she is broadcasting the very behaviour that has brought her so much shame. She says she can’t move on until the book comes out, but won’t The Widow just breathe new life into her ordeal?

“I wanted to try and understand what had happened,” she says. “This was a shattering experience for me. It certainly had the potential to wipe me out. I had all sorts of emotions running around, so I felt I had to do something.”

Tormented by guilt, Nola still thinks the affair was her fault.

“Did I create this because I wasn’t what he wanted?” she asks. “I thought we’d moved into a comfortable, content, middle-aged life, but I was the only one who moved into it – and I didn’t recognise that he hadn’t … I guess I wasn’t exciting enough, I wasn’t intelligent enough. I didn’t aspire to anything other than ordinariness – and he even took that away from me.”

Nola wonders whether she was too trusting, but how could she have known?

Even during the affair, Michael went to church every week – and hosted a home study group that discussed Christian ethics. The hypocrisy is jaw-dropping.

“There’s no moral struggle in any of those letters,” says Nola. “Quite the opposite: he considers that God sanctioned this Great Love – why would God give them this love if He didn’t want them to express it and enjoy it?”

Nola’s local rector has urged her to forgive Michael and Nola agrees that that has to be her goal. “If I don’t, all the negative feelings are just going to sap all my emotional energy for the rest of my life,” she says. “He was such a good person and I had a very fulfilling life with him, so I have to learn to remember all the redeeming qualities that he had.”

Michael didn’t get it all his own way, though.

Obsessed with the supposed superiority of their illicit love, Michael writes that he and Bea “occupy a dimension beyond ordinary experience” – and yet the affair came to its all-too-ordinary conclusion. Once Bea had earned her doctorate, she returned to her family overseas in 1997 and eventually ignored Michael’s letters and emails over the following decade.

Just six months before his death, Michael reached out to Bea one last time – only to be rejected again.

“Once she had her doctorate, she was finished with him, but he was still pining for her right up to the end of his life, which was sad,” says Nola. “When he was ill in later years and I’d sit with him, he’d take my hand and he’d look me straight in the eye and, with a gentle smile, he would say, ‘I love you’. Had I not found that last email to her, I might have convinced myself of that.”

In her book, Nola has changed the names of her husband and his lover.

This article originally appeared in the September 2013 issue of The Australian Women’s Weekly.