Head of the Australian Workers Union, Paul Howes has split from his wife, Lucy, it was revealed today. Four months ago, in a Women’s Weekly exclusive, Howes spoke for the first time about his adoption.

On the outskirts of a Sydney park, Paul Howes, one of the most politically recognisable men in the country, is trying to hide. At the entrance, a block from his house in the city’s inner-west, he is scheduled to meet the woman he has thought about his entire life. He’s so anxious, he calls a mate and pretends to be a “busy and important man”.

That was October last year and Paul had just turned 30. His birthday party a month earlier had made the newspapers for its diverse mix of influential friends. The most surprising thing about the party was not that he had influential friends, but that he was 30.

Elevated to the job of national secretary of The Australian Workers Union (AWU) at 26, Paul has looked and acted like a man 10 years older all his life.

By the time he was 29, he was so influential that he was being credited with taking a key role in the toppling of Kevin Rudd as prime minister.

After the 2010 federal election, Paul wrote Confessions Of A Faceless Man, about his role in the brutal coup which saw Labor narrowly avoid defeat after Julia Gillard scraped together a minority government.

Today, Paul is one of the PM’s strongest backers, despite his sometimes vocal criticism of government policy.

“I’ve known Paul a long time. While he’s grown up in the job, he’s always been basically the same Paul: upfront, courageous, never afraid to tell it like it is or stand up for what he believes in,” says the Prime Minister.

“Now, we don’t agree on everything, but what I admire about him is he’ll tell you that to your face and you can have a discussion about it. That’s the way it’s supposed to work.”

None of this is bad for a bloke who had a miserable childhood and dropped out of school at 14. Self-taught, Paul entered politics from Sydney’s Blaxland High School, which he left in Year 9 for a brief flirtation with the Far Left before joining the Australian Labor Party.

Not since former Prime Minister Bob Hawke and one-time leader of the Australian Council of Trade Unions Bill Kelty has a union boss had as high a profile as Paul Howes, eclipsing his mentor and predecessor at the Australian Workers Union, Bill Shorten.

It is the Queen’s birthday holiday and the rain is belting down in the small paved courtyard at the back of the Howes’ family terrace in Sydney’s inner-west. It is the wettest June day in five years, but there is not a sign of the mud or rain — the Howes’ home is immaculate.

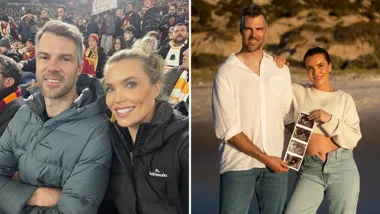

His wife, Lucy, is joking that he won’t get away with pretending to know where things go as he unpacks the dishwasher. As she says, “Let’s face it, he’s not here a lot”.

Two-year-old Sybilla has gone for her nap, while Sam, nine, and Zoe, six, are playing with friends across the road.

Lucy, a successful government lawyer with suppressed political ambitions of her own, met Paul in Young Labor and, within months of dating, she fell pregnant with Sam.

Paul was 20 and Lucy was only a year older. As she tells it, life was “fun”, even though her own middle-class parents were initially “horrified”. The worst thing that happened to Lucy was her parents got divorced when she was 20. “Whoa, rock my world,” Paul jokes.

Six months after Sam was born, the couple married in Fiji. Paul was happy. They struggled financially, but they were in love and jobs were starting to come easily to the ambitious young man. “We were happy. We never had any great expectations,” Lucy recalls.

To have an understanding of what drives Paul Howes, it helps to know what happened in the years after his adoption. Paul tends to gloss over the details or joke about his childhood, but he is adamant who is to blame for his early years.

He was born Benjamin Patrick on August 23, 1981, to a 21-year-old woman who reluctantly gave him up for adoption. Paul’s adoptive parents were Anne and Bob, but when their marriage collapsed, Anne married Paul’s stepfather Gary.

Paul was 12 when he left home to live with his mother’s first husband, the man he calls his father — Bob. Yet, for reasons which are not fully explained, that didn’t work out either. “Dad had a few problems and so I left his house when I was 14 and a bit. And then I didn’t feel I could move back into my stepfather’s house. So I moved out and moved to the city.”

Alone but determined, 14-year-old Paul proved to be very capable of getting ahead. “I didn’t have a flag and a shopping trolley. I wasn’t standing in the middle of the street speaking in tongues. But I didn’t have a fixed address for a while,” he says about his time sleeping rough.

Paul insists that his mother, Anne, was a saint and just trying to do her best with him while also raising two girls.

With nowhere to live, Paul moved around, staying with friends until he eventually got a job as a bank teller by claiming he was 21 when he was only 15. It turns out he lied about his age a lot and when asked why, he explains that he was just “really embarrassed”.

“I was embarrassed about not finishing school, lying about my age, starting work really young, leaving home, being uneducated.”

By then, Paul had successfully applied to be “legally independent” from his family.

“I think I just went and did it. I was pretty resourceful as a kid; I could always work out how to do things.”

It seems that was the turning point. From the bank, Paul moved into insurance and then quickly into politics, where he came under the eye of formidable mentors such as former NSW Treasurer Michael Costa and Bill Shorten, and the rest is history. Paul had gone from being homeless to one of the most influential men in the country in under 15 years.

Yet, for Lucy, there was something gnawing away at her and their family. “I think being a mother, I always felt there was this woman out there and she would probably want to know what happened to her child,” Lucy explains. She had evidence to prove that Paul’s birth mother was doing just that.

Buried in a drawer among his documents is the adoption paper, which tragically states that his 21-year-old mother had formed a “close bond” with her son in the short time they had together.

“Jane [not her real name] found it extremely hard to part with her baby with whom she found a very close attachment immediately,” wrote the case worker on the adoption papers.

In the end, it took five years and thousands of dollars to find her and, as fate would have it, she had been living one suburb away the whole time. Jane, who Lucy describes as “a very smart, classy lady” now has young children. One of them is about the same age as Sam.

There were many false starts and Paul was not always as committed as his determined wife. It was hard. The tough guy of the union movement says it was the hardest thing he has ever done in his life.

Before the meeting in the park, Paul wrote his biological mother a letter stressing that he was not sad or bitter about what had happened. They then spoke and his mother and her family quickly established who he was. It meant Jane already knew what he looked like before they met that day in the park.

“I was on the phone to my mate and we agreed he would call me after 15 minutes, 30 minutes and 45 minutes,” says Paul. “It was like one of those things when you go on dates — ‘Oh no, it’s an emergency! I’ve gotta run, I’m so sorry’. So I was lining that up.”

“But she saw you coming,” interrupts Lucy. “She was waiting for you to come out from behind the corner.”

Paul describes what follows as one of the most “gut-wrenching” moments of his life.

He says he and Jane talked for more than two hours, but there were long silences. “It was very sad, but it was very awkward, though, because we’re very similar. We don’t talk about a lot of things.

“She was from a very Catholic, established family and [they] pressed her into giving me up. She said, when I turned 25, she’d kinda given up. She thought if I hadn’t contacted her by then, I wouldn’t contact her, which is fair enough. It’s very sad for her.”

Jane revealed to Paul that she had kept baby photos of him for years and no one knew. “Her kids didn’t know. Her husband only found out because she used to cry for a week around my birthday every year. It’s very tragic.”

The relationship between Paul and Jane is very new, but it seems strong. Lucy is delighted by her new mother-in-law, especially as Jane’s daughter babysits for them most weekends.

On the other side — his father’s side — they’ve spoken, but the relationship is still a work in progress.

On the adoption papers, his father is described as a 25-year-old with interests in surfing, reading, writing and politics.

It turns out he was a journalist and a political staffer before having a successful legal career. In fact, the description on the adoption papers initially alarmed Lucy, who points out that it matches a young Tony Abbott, the current leader of the federal Liberal Party.

Mr Abbott started out as a journalist and once believed (incorrectly) that he’d fathered a son who was then adopted.

Essentially, this story has a Hollywood ending, but there were very low moments. “I kind of retreated into myself for six months and didn’t talk at home for a long time,” says Paul.

Asked if he has sought professional help, Paul jokes. “Lucy has been demanding it. But I have my own way of dealing with it — you bottle it up and then it comes out at inappropriate times!”

Ask anyone about Paul’s potential to lead Labor and people acknowledge he is the stand-out of his generation, but there are critics. His profile is so high, some wonder if he enjoys the limelight a little too much.

“Rightly or wrongly, power in this country at the moment is profile,” Paul says, “and if you don’t have a profile, you’re not in the story. So if you want your union to be in the story, you’ve got to have a profile.”

He is aware a “mucked-up childhood” can have its advantages as a long line of successful political leaders have a similar tale of parental abandonment. “They say one in five Australians have mental illnesses. I presume five out of five people involved in politics and public life have mental problems. It’s not an insult or anything, but I think being narcissistic in nature [helps in politics].”

The PM thinks Paul has more to offer than that. “Standing up to powerful interests around the country takes guts — something Paul’s never been short of,” she says. “I expect Paul to be around in public life a very, very long time.”

For now, Paul is more than content working at the AWU, but despite the critics and his stepfather, there is no doubt the next stop is Canberra.

.jpg?resize=380%2C285)