Scroll up to the top and take a look at the photograph. It’s a picture of an Aussie family at Christmas time. Mums, dads, grandmothers, sons, daughters – more cousins than you can poke a Christmas cracker at.

It may look for all the world like a typical family photograph. Except it’s not.

Instead, it’s a family portrait made possible by its one absent member. His name is Nathan. And while you won’t see him in this photograph, in the lives of every single person pictured here, he is ever present.

The story of this most modern of blended families starts back in 1992. December 19 to be exact – barely a week before Christmas. Nathan Westwood, a bright 20-year-old student had just completed his first year of medicine at Brisbane’s University of Queensland. Together with two mates, he had hatched a plan to drive to St George, in the west of the state, to go grape-picking and earn a bit of extra holiday pocket money.

His mother, Dianne, waved him off early on the morning of December 16, urging the three of them to look after each other and drive safely.

Later that morning and somewhere outside Goondiwindi, the trio found themselves following in the path of a lumbering petrol tanker. The driver of the truck would later tell an inquest the boys sat patiently behind him for some 15 minutes before the driver of their vehicle made the fateful decision to overtake. It was safe to pass – the day was clear, there was no oncoming traffic – but when a wheel caught the edge of the deep-rutted country road, the driver lost control of the car. Sitting in the passenger seat, Nathan bore the brunt of the subsequent crash.

While his two friends walked away unscathed, Nathan was airlifted to Brisbane, where doctors worked frantically to rescue him from severe head injuries.

Over the next 48 hours, some 200 friends and family of the aspiring sports doctor rallied – keeping a vigil at the hospital, supporting Nathan’s devastated family, praying for a miracle.

Yet the gods had other plans and on December 19, Dianne made the heartwrenching decision to turn off her son’s life support. Long before his death, Nathan had nominated to be an organ donor. And so, as Dianne said her final, tearful goodbyes, and while railing at the senselessness of her loss and convinced this was a pain from which she would never emerge, she bequeathed her son’s vital organs to medicine so that others might live.

“I remember that night like it was yesterday,” Dianne says now. “We spent time alone with Nathan in the ward, then walked alongside him as they wheeled him into the operating theatre and said goodbye.”

Across town, in another suburb of Brisbane, Terry Donovan was facing down a bleak Christmas of his own. Recently diagnosed with cardiomyopathy – an inflammation and enlarging of the heart – the then 51-year-old father of four had been told by doctors that unless he found a heart donor, he had no more than six months to live.

The news had devastated his small family: wife of 27 years Nook, daughters Karryn, Cathy, Toni and son Gregg.

Terry was too young to die. His kids had only just grown up: they were yet to marry, yet to produce families of their own. Terry had always been a pillar of strength in the Donovan clan – a former-rugby-playing, surf life-saving bear of a man. The possibility that he wouldn’t live to meet a single one of his grandchildren was unthinkable.

So when the call came on the afternoon of December 19 that a heart had just become available, he was at the hospital and prepping for surgery within hours.

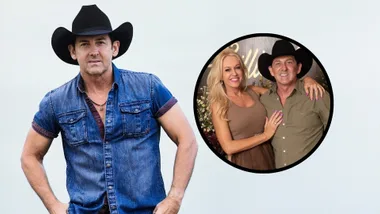

Terry Donovan and Nook.

Now usually, in organ donation stories, this would be where the tale ended. Strict privacy laws exist across Australia to keep donor families and organ recipients separated.

However, this being Queensland, where everyone knows everyone and it’s considered rude not to strike up a conversation with a stranger, the families eventually found one another.

It started when Dianne and Terry began communicating anonymously through their respective organ donation ‘co-ordinators’. On the first anniversary of Nathan’s death and after “a year of grief that I honestly didn’t think I would survive”, Dianne sent a yellow rose and a letter to Terry via their respective proxies.

“We had had yellow roses at Nathan’s funeral,” explains Dianne. “Yellow is a symbol of grace and faith and love.”

On the second anniversary, she sent two roses. On the third, Terry beat her to the punch and sent a rose bush.

And so, for eight years, they kept up regular communication through a third party – relaying all the news from their respective lives, signing their letters from “Terry” and “Dianne” – but never knowing exactly who the other was. Both would sit silently every year in a Brisbane church at the annual thanksgiving service for organ donor families and recipients, wondering if the other might be present.

Then, in the year 2000, Terry applied to run the Olympic torch as it made its way around the country in the lead-up to the Sydney Games.

“I’m running for my heart donor and my donor family,” he wrote in his application. Weeks before he took to the torch course, Terry put together the clues contained in eight years’ worth of correspondence, tracked Dianne down and tentatively made the phone call that would change both their lives.

“I had no words,” Dianne remembers of the call. “I was gobsmacked. It was a rush of mixed emotion.”

They met a week later – another day filled with trepidation and tears. When Terry ran his leg of the Olympic torch course a few days later, he did so with a photo of Nathan under his shirt, nestled against his fast-beating heart.

Fifteen years on and they are the best of friends. No, more than that: they are family.

Dianne, her husband Tom, her mother Mary and daughter Melissa are all regular attendees at Donovan family gatherings. Dianne and Tom have been to three Donovan family weddings and they always celebrate Christmas together. Eight years ago, when Terry’s son Gregg and his wife Anthea produced a grandson for Terry and Nook, they called him Nathan.

“At the time Terry received Nathan’s heart, he had no grandchildren. Now he has eight and one of them is named after my son,” says Dianne, wistfully. “We have been welcomed into the family from the day we met them.”

For Terry, now 74, the gratitude he feels is such that “no words can describe”.

“I remember meeting Dianne at my door that day and just crying,” he says. “I had prepared what I wanted to say and practiced it over and over. But emotion got the better of me and, in the end, all I could say was ‘Thank you’. I mean, what more can you say?

When I get up in the morning, the first thing I do is walk past the framed photo of Nathan I have in the hallway and think, ‘Gee, I am lucky’.

“I have seen all four of my kids get married and eight grandchildren be born, and none of it would have been possible were it not for the generosity of this family.”

Yet what is it like for Dianne to sit with Terry and hold his hand, and know that the life of this man – this relative stranger – is being sustained by her son’s heart?

“A year or so after having met and spent time with Terry, I asked if I could put my head to his chest and listen to Nathan’s heart beating,” Dianne recalls. “It’s hard to describe how that feels. It was difficult but empowering. It was beating away so beautifully.”

And beat it has continued to do – pumping blood and oxygen into body parts which even at 74 are unusually active.

Terry still competes at the World Transplant Games, where in the past 15 years he has won medals in countries as far-flung as South Africa, Sweden and France, in events as diverse as badminton, tennis and the 20-kilometre bike ride.

“Next year might have to be my last year at the Games,” he says, somewhat ruefully. “I’ve run out of people in my age group.”

For Dianne, the experience of watching Terry wring so much out of life in the 22 years since Nathan died has been simultaneously uplifting and bittersweet.

“If you had lined up a group of possible recipients and knew a little about each of them, I would absolutely have chosen Terry to take Nathan’s heart,” she says.

“He is so mindful of the gift he has been given. He is a wonderful caretaker of my son’s heart.”

She pauses, overcome with emotion. Her voice catches.

“You don’t ever get over it, you know? Never, ever. I know it is 23 years this Christmas and to a lot of people that might sound like a long time, but losing a child is something else again. You never get over it.

“My Nathan was named because it means ‘a gift from God’. Because that’s what he was to me. And that’s what he was to Terry.”