At around 5am on August 1, 2012, Sam* could hear a truck rumbling along the street.

He scrambled out of his bed and ran into his mother’s room, begging to go outside.

Without opening an eye, she grumbled yes at the familiar request, then went back to sleep.

Sam and his older brother ran to the front fence and waved at the truck until it vanished from sight.

Then Sam went back to his bed in his small brown brick home in Melbourne’s northern suburbs, while his brother switched on the early morning cartoons.

Every week without fail, when the local garbos were doing their run, often long before dawn, the familiar little boy in the pink pyjamas would stand at his bedroom window and wave at them while they loaded bins, or run out to the street to greet them.

The garbos loved seeing the little fella and his excitement at seeing them brightened up an otherwise routine rubbish run.

He loved it when they gave him a wave back or a toot of the truck’s horn.

Little did the garbos know, by the time they knocked off work that cool winter morning, their little mate in the pink pyjamas was dead and not only were they the last people to see him alive, they were among the few who even knew he existed.

Because this is the story of the little boy who never lived. Except he did.

A little boy whose birth was never registered, who never went to kindergarten, never saw a doctor and was never immunised.

A little boy who didn’t have play dates, didn’t ride his bike on the street, never went to the local park, who at age five never attended school. On paper, Sam didn’t exist.

His mother gave birth to him at home and he was rarely allowed outside, except when she locked him and his older brother out of the house, often naked, because she was sick of them.

Immediate neighbours, the only people other than the garbos who knew Sam existed, sometimes overheard the little boy begging his mother to let him back inside and they also overheard her threatening to break his arms and legs, and run him over with her car.

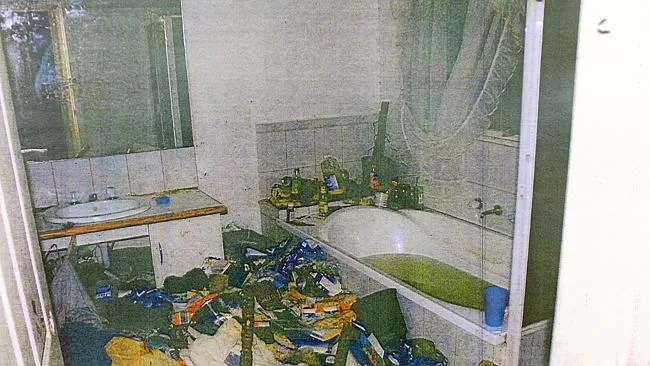

The official cause of Sam’s death is“unascertained”, but forensic doctors believe he contracted a serious bacterial infection after cutting his toe on an open tin of cat food left on the floor of his parents’ home, a house so squalid it was described as “unfit for an animal to live in, let alone a human”.

When police attended the premises, the floors in every room of the house were covered with household rubbish, rotting food and opened cans of pet food.

There was human and animal faeces smeared on the walls, broken furniture, upended chairs and tables, and broken toys everywhere.

Hundreds of bags of rotting, rodent-infested rubbish were piled up.

Hardened police vomited when they entered the home to investigate.

Sam is not his real name. For legal reasons, his identity can’t be revealed. Yet as the shocking details of this case unfolded in court, authorities are questioning how, in modern-day Melbourne, a child can live and indeed die in such horrific circumstances.

“Filth is a generous description,” says Victorian County Court Judge Michael Rozenes.

“Authorities had no knowledge a child even lived there because if they did, the child would have been removed. In every sense, this is truly tragic, [both] his death and the conditions he endured in his short life.”

It was the afternoon of August 1, 2012, when Sarah* knocked on the door of the local ambulance station.

Her son was lying naked on the back seat of her car, not moving, his skin grey and mottled. The young ambo rostered on that afternoon picked up the lifeless child and rushed him into the station to begin CPR, but it was too late. The child was dead.

Sometime during that day, while his father was at work and his mother slept, Sam had died.

Three days earlier, the little boy had cut his toe on an empty tin of cat food left on the floor of the family home.

The autopsy report says that his emaciated body was covered in dirt and an “unpleasant”- smelling blood- soaked bandage wrapped around the toe was “sodden”.

When police arrived at the family’s home later that evening to question his parents, they were shocked by what they saw.

“In my 26 years with the police force, I have never seen or been in a house of such squalor,” says a veteran detective sergeant. “The house was not fit to be lived in by humans, much less animals.”

Sam’s older brother, Andrew*, then seven, gave a heartbreaking account of Sam’s death to detectives, describing how he’d been “like a zombie” the night before he died.

“Last night, he kept falling over… boing, boing. I knew he was sick … very, very sick. [He said] ‘Help, help’, and I walked into his room, and he said, ‘Could you pick me up?’, and I picked him up and held his hand, then he tells me ‘help’ again. We went and watched some cartoons, and I helped him, I gave him a drink.”

Andrew was worried about Sam when he went back to bed after the garbos had been. He said Sam sounded “very, very, very terrible. Sound like he gunna die”, after he asked Andrew for water in “sad kinda talk”.

Police and community services have been left to puzzle over how life went so wrong for little Sam.

His parents were a young professional couple when they met in 1996. She was a legal secretary, he was an executive in the lucrative energy industry. It was a whirlwind romance and, a year later, they married in a traditional Catholic ceremony surrounded by family and friends.

The newlyweds bought their first home in a picturesque new suburb just a few kilometres from the city.

They were a hard-working couple, financially well off and proud of the life they were building together.

Baby Andrew arrived in 2004 and they purchased two investment properties.

On paper, life was picture perfect. Yet sometime between the birth of their first son and the arrival of Sam in 2006, things began to go horribly wrong.

In July 2014, Sarah and her husband pleaded guilty in the Victorian County Court to multiple charges relating to Sam’s death.

Yet after entering their pleas, Sarah collapsed in the dock and later died in hospital.

She had severe mental health issues and suffered organ failure related to long-term alcohol abuse.

Her body and her mind had shut down. The statements she made to police immediately after Sam’s death are now the only clues we have as to how the life of this young mother unravelled so badly.

Posthumously, psychiatrists have diagnosed her with severe post-natal depression. They believe she was in a dissociative and delusional state. When Sarah was questioned about the state of the house in her police interview, she said, “I just got overwhelmed. I’ve always been a bit of a procrastinator.”

She described her home as “a hovel that was unfit for humans to live in”.

She said the house had been like that for two or three years and when asked why she didn’t seek help, she said it was shameful and embarrassing.

“It’s sheer and utter filth,” she told investigating officers.

“We recognised that we f****d up, we failed.

We did not provide an environment that our children or any human being deserves to live in.”

According to police evidence tendered in court, it was about lunchtime on that August day that Sarah woke up.

She told detectives she assumed Sam was still asleep in his room and never bothered to check him because “if he was hungry, he’d come out” to her. She sat down to watch TV and, by 3.30pm, when Sam still hadn’t come out for lunch, she went to find him.

She looked in his room, he wasn’t there.

When she went into the spare bedroom, she could see his legs lying across the doorway and although she yelled at him, he wouldn’t wake up.

Andrew recalls the moment when his mother realised something was horribly wrong with Sam.

“She checked on my brother. No breathing, he didn’t look right,” he told police.

“Then she scooped him up and put him on the bed in Dad’s room. And then she can’t hear any heartbeats and then she start pushing him like the doctors do [on TV] and more and more and more, and then breath, blow into his mouth, then nothing happened. He’s dead.”

Police prosecutors revealed that Sarah had printed up fake school certificates, made up homework sheets and often told her husband she’d spent the day doing tuckshop duty when, in fact, her children had never attended school.

She’d coached the boys to tell their father school was “great” if he asked, but neither child could recite the alphabet beyond A, B and C.

In court, Sam’s father sat with his head in his hands, sobbing, as Judge Rozenes gave voice to the bewildered faces gathered in the courtroom.

“He wasn’t suspicious that he never went to a parent-teacher interview? Never went to a school play or sports day? It beggars belief he couldn’t see something was wrong.”

Sam’s father said that on three occasions he’d ordered giant skip bins and cleaned the house out, but within days, the rubbish began piling up again.

He said he had encouraged his wife to seek medical help, but she refused and threatened to take the children away if he intervened. On one occasion, she made good with the threat and disappeared with the boys.

Unable to combat her deteriorating mental state, he simply gave up and turned a blind eye, leaving for work early in the morning and coming home late at night.

He slept in the spare bedroom, which he kept clean.

He said he didn’t feel responsible for Sam’s death and that his wife was a “magnificent mother who

spoiled the kids rotten”.

Sam’s father was sentenced to three years in prison, but his sentence was wholly suspended and he will not spend a day in jail.

In handing down his verdict, Judge Rozenes said he decided the man had been sufficiently punished through the loss of his family – Andrew is no longer in his care – but slammed his actions nevertheless.

The Principal Commissioner of the Commission for Children and Young People, Bernie Geary, says he is simply at a loss to understand how a child can slip through the cracks so badly.

“When a child is neglected, the pain and trauma that comes as a consequence must be shared by us all,” he says.

“Children live in families, but also in communities … These two little boys were, sadly, living in a community that had its opportunities to care, but turned away. I am hopeful that this little boy’s death inspires an instinctive response in the future.”

Names have been changed

This story was originally published in The Australian Women’s Weekly.