As a little girl, Sigrid Thornton was blithely unaware of the vicious death threats targeting her family.

Aged six, she was still too young to realise the police cars parked in their quiet suburban street were lurking to protect her radical parents from their political enemies.

It was March 1965, and Sigrid’s feisty, outspoken, audacious mother was making national news – and becoming a feminist icon in the process.

Merle Thornton and friend Ro Bogner had sent shockwaves through the establishment after chaining themselves to the bar of Brisbane’s landmark Regatta Hotel, demanding that women be allowed to drink there alongside men.

“Mum has never exactly been a shrinking violet,” laughs Sigrid, whose iconic roles play like a greatest-hits reel of Australian film and television, from The Man From Snowy River to All The Rivers Run, Seachange, Underbelly, Prisoner and Wentworth.

“She has been a fighter all her life and I admire her bravery and dogged determination. I suppose I learned how to be strong and independent from that example, although it’s really hard to unpick because the empathy that exists between parent and child is so strong.”

“Certainly it’s pretty difficult to grow up with such a very, very strong personality without being imbued with some of the same characteristics.” Merle nods, approvingly.

“It’s the age-old thing, isn’t it? ‘I don’t want to be like my mother,’ and then realising that I am like my mother and becoming more and more like her as time goes by!”

Sigrid flashes the infectious smile so obviously inherited from Merle, together with forensic intelligence, bone-dry wit, a passion for fairness and that distinctive heart-shaped face.

“Back then I didn’t fully understand the issues, but I was very aware of the Regatta protest because we were allowed to stay up late and watch Four Corners on telly,” the award-winning actor and producer fondly remembers.

“I didn’t know about the death threats – I vaguely remember a little bit of scuttlebutt about that – because our parents largely tried to protect us from the darker side of what went on.

“But growing up in an environment of social activism – not just in terms of women’s liberation, but more generally – wasn’t always the easiest thing.

“It’s a natural response for small children whose parents are out there doing things for other people to think, ‘What about me?’ although that wasn’t exclusive to being the daughter of a feminist. It would have been exactly the same had Mum been a brain surgeon.”

Sigrid admits that she becomes more and more like her mother as time goes by.

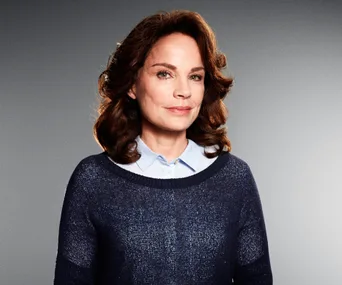

(Credit: Photography by Alana Landsberry. Styling by Mattie Cronan.)In The Australian Women’s Weekly‘s light-filled studio before the COVID-19 shutdown, a small legion of stylists, publicists and hair and make-up artists are fussing over Sigrid’s diminutive figure.

She is businesslike and charming, yet her focus keeps defaulting to Merle who is pacing nearby, waiting for the shoot to begin.

“Mum, darling, sit down,” her daughter chides with obvious affection.

“You were up before dawn and you’re going to be standing for a very long time today. We don’t want to wear you out.”

Merle, however, is made of sterner stuff.

Now aged 89, the redoubtable writer and former teacher – who introduced a ground-breaking women’s studies course at The University of Queensland – shows scant sign of slowing down and has just released a compelling new memoir, Bringing the Fight, a firebrand feminist’s life of defiance and determination.

As her book reveals, the fearless mother-of-two fiercely battled injustice wherever she found it.

And in Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen’s notoriously oppressive Queensland – where public bars remained ‘men only’ havens until 1970 – there was a cornucopia of discrimination to be set right.

Sigrid won an AACTA Award in 2005 for her role in Peter Allen: Not the Boy Next Door.

(Image: Getty)Incredible as it now seems, women working in the state and commonwealth public services were forced to resign after tying the knot. (Merle hid her own married status for years, until pregnancy forced her to go public.)

There was no recognition of de facto rights for females who bucked the system by “living in sin” with their partners, and birth control was largely a taboo subject.

A born rebel, indulged only child and self-styled “girly swot,” Merle set out to change these self-evident inequities, supported by her adored “male feminist” husband Neil.

The couple met at a Workers’ Educational Association poetry class, studied at The University of Sydney (he read philosophy, she graduated with an arts degree) and became active in the free-thinking Libertarian Society.

So it was not an immediately natural fit when Neil’s academic work saw them move to the then backwater of Brisbane, where Sigrid and older brother Harold grew up surrounded by heated political debate.

“Queensland became a breeding ground for anarchy and upheaval and uprising, because the state government was so repressive – the most repressive in the country.”

WATCH BELOW: Sigrid talks about her return to the revival of the classic Seachange. Story continues after video.

Famously, the Thornton family was arrested en masse by Queensland police at a Vietnam Moratorium rally when Sigrid was only 13.

“I was scared that people were being hurt but I never imagined, in my naivety, that I was in any danger,” she says.

“I was an optimistic teenager and I had my mother by my side. I think I saw it as an interesting adventure.”

It must have been difficult to shock parents like Merle and Neil, who espoused free love in the straight-laced 1950s and had a generally eccentric approach to everyday life.

Setting up house together, they owned nothing but highball glasses and teaspoons.

“That was all. No dinner plates or bowls, no cooking utensils or cutlery.

I should admit I wasn’t cut out to be a homemaker,” reminisces the Thornton matriarch who, on one memorable occasion, scandalised her grandmother when a diaphragm fell out of her handbag onto the carpet.

Nonetheless, young Sigrid tried to push the envelope.

Wanting a bra – “I didn’t really need one” – she was forced to hide the nefarious underwear in a bottom drawer, so a disapproving Merle would not find it.

Earlier, there was a memorable clothing “barney” when her mother sent her to kindergarten in overalls home-sewn from men’s suit material, instead of a more suitable dress. The teacher was not amused.

Merle, in her turn, failed to see the funny side when her daughter came home from pre-school and announced that she might become a nurse one day.

“I looked at her quizzically,” her mother writes.

“‘You’re a smart cookie, why don’t you become a doctor?’ Without missing a beat, she replied, ‘Women don’t be doctors.’ We pulled her out (of that kindergarten) quick smart.”

No wonder Sigrid says wryly, “There were a few barneys! I laugh about it now but at the time it was normal, just life. It takes quite a long time to realise there’s something else going on outside the family, and other people with other ideas.”

“It’s very like actors’ children, who tend to grow up thinking everyone’s parents are on TV. For a long time I just thought every adult did what my parents did.”

An understandable assumption. Yet few parents, then or now, would send their children to New Zealand for a year to stay with friends while they pursued their own academic careers in the UK and Australia.

Occasionally, perhaps inevitably, Sigrid wished the Thornton clan was more conventional. That long separation was anxiety-inducing, although she downplays the downside.

“It may have been harder for me to rebel, but not impossible,” says Sigrid slyly, producing a cheeky grin from both mother and daughter.

(Credit: Photography by Alana Landsberry. Styling by Mattie Cronan.)“As a small child I wanted to be called Mary, because no-one knew how to pronounce Sigrid. As a child, everyone wants to be like the other kids,” she chuckles.

“A minor tragedy of my little life was that I never got rainbow-coloured greaseproof paper for my school lunch – it was just a brown paper bag – and we didn’t have soft drink in the house.

“I’m really being flippant but although we lived in an unorthodox environment, we knew it was better than the other way around. It may have been confusing, and definitely more challenging, being the child of activist parents, but ultimately it gave me more resilience and a set of values I still hold dear.”

Sigrid, a chip off the old block who keenly promotes gender equality through various screen industry boards, pauses then concedes: “But it is certainly unusual to meet others who had that same upbringing.”

“It may have been harder for me to rebel, but not impossible.”

A wide grin.

“I had miniature Saffy phases – you know, like Ab Fab – and managed to get up to all sorts of mischief.”

Merle chortles, “Oh, good.”

Their tight bond is obvious and the loss of much loved Neil, who died at Christmas 2014 following a long illness, has brought them even closer.

Sigrid received a Queen’s Birthday Honour medal from the Governor of Victoria, Linda Dessau in September 2019 for her contribution to the Arts.

(Image: Getty.)“Mum’s health has been up and down for quite a while now and it’s a big birthday coming up later this year, so we need to take it a little bit easier these days,” Sigrid explains.

“But she’s in good spirits and brimful of ideas. So there are a great number of deep and important conversations we can still have.”

“Mindfulness is something people 60 years my mother’s junior are striving for, so she should enjoy living in the moment. We’re living in it together.”

Today they live nearby in Melbourne, speak on the phone virtually every day and, before self-isolation was our routine, regularly got together at the book-filled home Sigrid shares with producer husband Tom Burstall, her partner of 43 years and father to their two adult children, Jaz and Ben.

Her parents provided the template for a long and happy marriage, but so much more besides. Persecuted at school in London for being a sun-tanned Aussie outsider, Sigrid was sent to drama classes to buoy her confidence – cue the genesis of her glittering career – and she was also encouraged to protect herself by other means.

Merle and Neil taught her that projecting a forthright brand of take-no-prisoners intelligence could discourage bullies, and later workplace predators, alike.

WATCH BELOW: Sigrid and her fellow Wentworth cast members on the 2019 Logie Awards red carpet. Story continues after video.

Her mother was on-set chaperone from Sigrid’s first professional gig, aged 13, until the fledgling actor turned 16.

“And I always thought it was fortunate that regulation existed, for both of us,” Merle says.

“Because a lot of young girls in that situation could have been at severe risk. Boys too. It was a juvenile thing, really, not a gender thing.”

Yet even when Sigrid went solo, sex pests stayed away.

“I don’t have any salacious #MeToo stories and I’ve given some thought as to why that is the case,” she ponders, always analytical.

“I really think my mum and dad probably equipped me very well. They gave me a fairly strong sense of autonomy and personal dignity, and therefore an ability to just perhaps cut things off … at the pass!”

A good joke, delivered with a straight face. She is serious about her family, work and the many worthy causes she supports, from saving Melbourne’s Victoria Markets to Vision Australia, Greenpeace and the Reach Foundation.

Unexpectedly however, especially for someone who confesses she is sometimes too intense, Sigrid Thornton AO revels in poking sly fun at herself.

It’s another trait she shares with her formidable mother, together with blistering honesty.

“I do think we are alike in some ways,” says Merle.

“But Sigrid is much better at positioning what she’s doing in a public sense than I am. I just blunder in and hope for the best. She is more likeable as an individual – I think that’s quite a difference between us – and Sigrid has a longer fuse.”

“Yes,” she readily agrees. “I do have a much longer fuse, but don’t get to the end of it, please!”

A gleeful whoop.

“It’s many, many miles longer and I have probably learned that from Mum, learned what to do and what not to do!

“It might not be coincidental that she said to me years ago, when I was still almost a child, ‘You have chosen a career in which excellence is still encouraged in women.’

“That’s been a great boon and made me an ambitious person. I think ambition has a bit of a bad reputation but I don’t see it that way because I think it drives resilience and tenacity.”

The pair are harmonious, yet acknowledge their differences in attitude and composure.

(Credit: Photography by Alana Landsberry. Styling by Mattie Cronan.)“Mum has had to be brave and tenacious and resilient all her life, no doubt about it, while I have probably spent more of my life being a people pleaser than she ever did. But she taught me independence and a need …”

She hesitates, examining how best to express her feelings.

“A need to move forward into what authentically seems the right approach for a situation, even when that might be the more difficult road to take – moving towards what is right and fair. And of course I also became a feminist!”

Nonetheless, Merle must have been a hard act to follow. Was it ever difficult to live up to her extraordinary example?

“I think I forged my own path, and I very much have my own views about feminism that may not always coincide with Mum’s,” Sigrid confides, green eyes bright with humour.

“We’ve had some robust discussions and they are always useful. Not always very pleasant, but always useful.”

So what does this dynamic mother/daughter duo disagree about?

“It’s more in the detail, although there are some more fundamental things but they’re not for public consumption,” Sigrid answers, diplomatically.

“The relationship between mothers and daughters is very deep and complex. That will go into my memoir, if I ever write one. Maybe.”

Bringing the Fight by Merle Thornton is published this month by Harper Collins.

The Australian Women’s Weekly May 2020 edition.

(Image: AWW)