It is shortly after midday on a sunny Wednesday in Hollywood and Oprah Winfrey is sitting cross-legged in an armchair with her bare feet tucked under her bottom. We’re playing a little game. It doesn’t have a name, this game, but play along if you like. The idea involves gently closing your eyes and imagining yourself at your own 100th birthday party. You don’t actually have to be 100 years old; the beauty of this game is you can look and feel exactly as you do now.

The point is, you’re standing there and all the guests are smiling in your direction. Now take a closer look, for these are not just any guests. In this game, you’re allowed to invite anyone you want to your party. They don’t even have to be alive anymore. They can be people you knew way back when, who have perhaps passed on; they can be as old as they were the last time you saw them, or people you know today.

So, who do you see?

Oprah places her hands on her bent knees and pulls them back toward herself.

“This is great,” she says, happily. “I would certainly like Nelson Mandela to be there.” Then, “Okay, here’s my posse. If you come into my house right now, there are four pictures on the walls: Nelson Mandela; Quincy Jones; Maya Angelou; Tina Turner.”

Very good. Who else?

“My best friend, Gayle.” (That’s Gayle King, who has known Oprah since they worked together in Chicago in their 20s. They are so close that some people think they must be lovers, which Oprah finds hilarious.)

So Gayle is there. Who else?

“Ah, let’s see … Stedman, of course. He would be there, steady as a rock,” says Oprah. (Stedman is Stedman Graham, who has been Oprah’s actual lover and partner since 1986.) “I’d like to see my great-nieces. One is three; the other is nine. Hmm … I’d like to have a gathering of people whose lives were touched in ways I could never imagine, from watching the show.”

Perhaps some of the girls from the Oprah Winfrey Leadership Academy in South Africa?

“Yes, of course. Yes, the girls who are closest to me, girls I have sort of adopted, so my adopted daughters would be there,” she says, “There are 20. They can all come.”

And … your son?

“Yes, I’ll have him there, too,” says Oprah, and not only would she have him there, she would – for the first time – hold him in her arms and perhaps even bestow a name upon him because, honestly, why wouldn’t she?

The birth – and the death – of that little boy marked a significant turning point in Oprah Winfrey’s life. On some level, she owes him everything.

OPRAH Winfrey is coming to Australia in December. Perhaps you already know that and, as a hardcore fan, you already have your ticket. On the other hand, perhaps you’re thinking, “Hmmm, for 25 years Oprah was on TV. Do I really need to see her again?”

Now, see, that’s where you’re looking at it all wrong. As far as Oprah is concerned, this tour isn’t about you going to see Oprah. This is about Oprah wanting to see you.

Maybe you’re thinking, “Ha, ha, of course she wants to see me.” Yet actually she does. As those hardcore fans know, Oprah isn’t about shouting “WOW” and giving away cars anymore; she’s about gathering as many people as she possibly can together, in stadiums or online, to pass on what she has learnt about living your best life.

If that sounds twee, hear her out.

The Weekly met Oprah one-on-one at the OWN headquarters (the Oprah Winfrey Network, which she founded and controls) beneath the famed Hollywood sign. She keeps her office at the end of a quiet corridor. There is security on the gate, at the front entrance and again at the door. A receptionist with a fancy headset sits right outside and they’ve all got their work cut out for them keeping tabs on the boss.

Hearing voices, Oprah comes – barefoot and tugging up the back of her blue denim skinny jeans – into the hallway to see what’s going on.

“I can’t find my shoes,” she says, but apparently that’s not unusual. Turns out Oprah is the kind of person who kicks off her shoes when she gets down to business.

First impression? People think she’s big – Oprah’s weight has been its own news story over the years – but like everyone from TV, she is much smaller than you might imagine. She’s also nimble. When she takes her seat, it’s by placing her hands on the Provincial-style armrests of her chair and lifting herself, legs already crossed, onto the cushion.

Besides the skinny jeans, she’s wearing a black jumper and a matt-white pedicure (matt-white being on trend in Los Angeles right now). She pulls her hair back from her face and the effect is astonishing. Her skin is luminous. They should put her in a L’Oréal ad.

The interview is likely to be the only one Oprah does ahead of her tour. We begin by talking about why she wants to return to Australia – “because I believe in supporting people who supported me” – and by nutting out a little of what she hopes to share with her audiences.

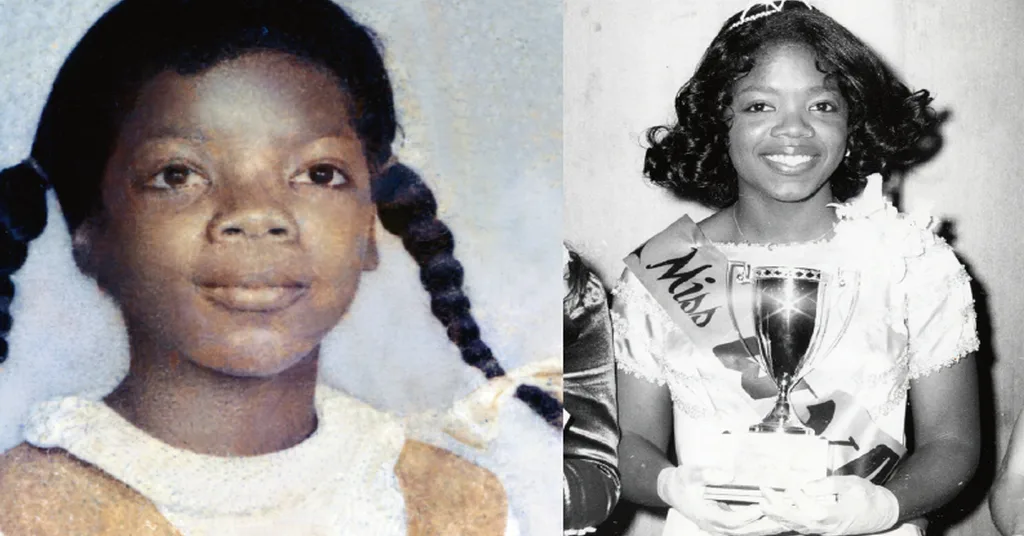

Oprah as a young girl (left) and as the winner of a beauty pageant in 1971, at a time when she felt she had to take charge of her destiny.

No question, they will hear a little of her own life story. It is extraordinary: Oprah was born in race-segregated Mississippi in 1954 to parents who barely knew each other (the way Oprah tells the story, her father, Vernon Winfrey, was “curious as to what was going on” under her mother’s skirt and soon enough found out).

Oprah’s mother, Vernita Lee, had no facility to raise a child, so Oprah went to live with her ageing grandmother, Hattie Mae Lee, who had been a domestic for a white family. Oprah’s mother went north to Milwaukee to work as a housemaid. Oprah says she has no memory of her mother before the age of six, when she was suddenly sent to live with her because Hattie Mae was dying (she passed away in 1963, shortly after Oprah turned nine).

“So at six, I am introduced to this woman who I’m told is my mother,” Oprah says, and none of the normal feelings – love, joy at being together again – were there, “and so for years, I was asking the question … what is a mother? What are you supposed to feel about your mother?”

It seems Oprah’s mother wasn’t sure how to love this little girl, either.

“I had an incredible spiritual base … a belief in a God that was up there,” Oprah says, pointing skyward, “and I relied on that a lot, but my overwhelming feeling was: I am alone. I must take care of myself.”

Oprah with her best friend of many years Gayle King.

Oprah’s transition to her mother’s care failed. She was shipped off to live with her father in Nashville, Tennessee, but within a year, she was back at her mother’s, where she was molested by a cousin, abused by an uncle and neglected by those who were supposed to be looking out for her.

By 14, she was pregnant.

A termination would not have been easy to get in the late 1960s. In any case, Oprah never considered it, although not for the reasons you might think.

“When I got pregnant, I didn’t even know what pregnancy was,” she says, leaning forward in her chair to emphasise every word. “The idea of ‘ending it’ wasn’t a notion. I – did – not – know – what – it – was. I was getting bigger every month and I realised, something is happening to me. I asked some girls at school. I literally had to look up ‘how long is a pregnancy?’ Okay, nine months, and then I guess I have to kill myself.”

Oprah went into labour prematurely and her baby, a little boy, died before he left the hospital. These are difficult matters to discuss, but was she allowed to hold the baby? Name the baby?

“No, no, no, no,” says Oprah, shaking her head. “No. I didn’t have any of that. Nor did I have any connection. I was just in a confused whirlwind of denial. Huge denial.”

Given that she was still a child herself, Oprah probably needed permission to grieve, but no such permission was forthcoming. She was, she says, so deeply in denial that it “never even occurred to me to name him”. She resolved instead to do as everyone else was doing and carry on as if nothing had happened.

Something had happened. The teenage Oprah’s life had been roiling out of control. The stunning experience of pregnancy and the death of her son proved an elucidation. It was then that she made herself a silent promise: I am getting out of here. Oprah left her mother’s home and moved back to Tennessee. With the encouragement of new teachers, she became an A-grade student. In short order, she won a full scholarship to Tennessee State University; a Miss Black Tennessee beauty pageant; a speaking competition; and a job on local radio. By 19, she was co-anchoring the news. From there came a talk show. Within a year, she had overtaken Phil Donahue in the ratings.

In years to come, Oprah would spin her early childhood experience – the poverty, the lack of affection – into a powerful narrative. She tells The Weekly, “Had I been born in a family where I felt nurtured, supported or loved, I would not be where I am today. I would have had far less need to prove that I was worthy of space in the world.”

Also key to Oprah’s success was this: the Oprah Winfrey Show wasn’t about Oprah. It was about her guests. Ordinary people would turn up and say things they had never said to anyone – how they had let their boyfriend hit them, or how they were molested as a child – and at the end of the segment, they would cry.

Oprah would often cry, too, the paradox being that even as she was healing others, she was herself plagued with self-doubt. One of her earliest attempts to try to make things right – and this is achingly typical of girls who feel uncertain of their worth – involved emptying her own bank account to retire both her parents.

Oprah with her long-term partner of almost 30 years Stedman Graham at the 2015 Academy Awards.

With the benefit of a lifetime’s learning, why does Oprah now think she did that?

“Well, lots of demands were being made on me,” she says. “When I started to make money, I had a lot of cousins all of a sudden. It started when I was in radio – they would ask for $50. Then when I was on TV, for $500. Then one cousin came up to me at a family picnic and said, ‘I need $5000’. I’m like, really? We are at a family picnic and you need $5000? Then, when I became wealthy, everyone’s like, ‘You’ve got to take care of your mother!’ My own mother is like, ‘You’ve got to take care of me!’ And I’m like, ‘But what are you supposed to feel for your mother?’ I still didn’t know. But my moral code is, basically, what is the right thing to do? So I did it out of a sense of responsibility.”

She pauses, then adds, “And also as my way of saying, ‘Thank you for taking care of me. Even though there are times when I think you could have done better, I know you did the best you knew how to do.’”

Oprah’s efforts to make good with her mother were almost certainly part of an unconscious strategy to bury the past. Yet, as a fellow Mississippian, the Nobel Prize laureate William Faulkner put it, that can’t be done: “The past isn’t dead. It isn’t even past”.

Deep within Oprah lay the fear that the story of her teenage pregnancy would come out. Predictably enough, it did, having been sold by her now dead half-sister to the National Enquirer for $19,000, in 1990. Oprah spent the night before publication in the bathroom, throwing up, her fear at once fundamental and probably universal: “I’m not worthy and now everyone is going to know I’m not worthy”.

She braced for a public thrashing. The universe yawned in response. Any fool could see that this wasn’t Oprah’s fault.

She had barely been 14 years old.

Oprah opening the Oprah Winfrey Leadership Academy in 2007.

With no secrets left to hide, Oprah strode forth into a shining future. Except that she didn’t, not really. “You can tell people they are worthy of space in the world,” she tells The Weekly, “but nobody believes you the first time.”

Even Oprah? Even Oprah. One example: way back in the late 1980s, Oprah met this guy, Stedman Graham. He was tall and handsome. Oprah doesn’t fit into Hollywood’s preferred body type (skeletal). She became convinced that people would look and think, “Why is he with her? He could do better.” She decided she had to lose weight and that battle became very public. Viewers were treated to hilarious footage of Oprah thrashing herself back and forward on a rowing machine, and saying no to Key lime pie, and although she kept saying it wasn’t for Stedman, actually, honestly, deep down, it was about Stedman.

Never mind that he had already chosen her. That little voice inside her head kept saying, “You’re not good enough, are you?”

The years went by and Stedman – not oblivious to this, necessarily, but kind of bemused by it – proposed. A delighted Oprah said yes and planning for the wedding commenced in earnest … and then it never happened. Why not? Because, blessedly, things were changing.

“Okay, so this is what happened with the wedding,” Oprah says, clearly delighted to be able to explain. “It was going to be September 8, 1993. My friends, they organised … what do you call it? An engagement party. And I’d been saying to Gayle, oh my God, oh my God, I’m feeling sick. I’m sick. I’m ill.

“She said, that’s cold feet. I said, no, this is not cold feet. This is feet in a concrete bucket, walking down the aisle. I don’t think I can do it.

“Then, about a month before the wedding, I was in a limousine in Miami with Stedman. We were coming back from a big party to celebrate my book coming out [the book and the wedding were due to take place within days of each other] and Stedman said, in the limo, you know, I don’t want this [the wedding] to be all about the book, the book, the book. So I think we should postpone this wedding. Otherwise, it’s going to be all about the book.

“And I said, okay. And I felt such relief! Like, ahhh. And in that moment, I thought, why do I feel such relief? And you know the answer. It was because I just wanted to be asked. That was it! I wanted to know that you cared about me enough to want to marry me, but I don’t actually want to be married.”

So she didn’t get married. That was two decades ago. She’s still with Stedman and still not married, so can we assume that is when Oprah truly stopped pretzeling herself – contorting to meet the expectations of others – and started living for herself?

No.

“When did that really happen?” she says. “I mean,

I started thinking about it in my 40s, then I turned 50, and Maya Angelou said to me, ‘Your 50s are everything you’re meant to be’, and I’m like, ‘I’m 50 and that’s it! Never again will I do something I don’t want to do!’ But it’s not true. You have to be told over and over and over again.

“So I would say it was ending the Oprah show [in 2011]. That was major. It was stepping away from hundreds of millions of dollars. And people were saying, but you have built a company of 500 people and they have kids in school, and these people depend on you. But I heard myself at one of the makeovers – and we had done 150 makeovers – saying, ‘Oh my God, wow, what have you done with her hair?!’ and I just didn’t feel it. And I didn’t want to be performing. I didn’t want to break my sacred trust with my audience. I knew then, I don’t want to do dog tricks and go YAY!!

I want to talk about how women – and girls – can better themselves. Show them why you keep making the same mistakes. Help people find their purpose and live the very best version of themselves.”

Oprah with friends Halle Berry and Beyonce.

In the years since she quit the show, Oprah has put herself firmly on that path. She personally teaches a course at her Leadership Academy called Life 101 (it’s everything she wished she knew before she left high school). Many of the girls who attend the class have been abandoned or abused, and some now live in the US. Oprah calls them “my adopted daughters” and the process of guiding them towards adulthood would appear to be as joyful and as challenging for Oprah as it is for any parent. “I get frustrated, but you know with raising children, sometimes you have to say the same thing over and over. I say, ‘I believe in you’ and they say, ‘But Mum O … ’ and I say, ‘No, I believe in you’. But you have to say it again and again.”

Then, too, she has the tour. It’s been to the US and Canada, and now it’s coming to Australia and you have been warned. There won’t be any dog tricks. Nobody is going to get a car. This is about you finding out your worth.

You have to figure it out, because until you do, life tastes like sand.

Naturally, this message has been written off as low-brow, daytime talk-show pop psychology, which couldn’t bother Oprah less and why should it? Here is a woman who rose herself up from her knees to embrace the whole world. There is nobody she hasn’t chased down in search of answers. In a career spanning three decades, Oprah has asked Nelson Mandela and Maya Angelou and Elie Wiesel and Toni Morrison and Cormac McCarthy and Barack Obama and even the Dalai Lama: What’s our purpose? Why are we here? How can we be happy?

Passing on what she’s figured out – that’s the basis of the tour.

The first graduates of the Oprah Winfrey Leadership Academy for Girls in 2015, a school which Winfrey statred in 2000.

YOU know that little 100th birthday game? How it starts with you putting together a guest list? Well, it ends with somebody standing up to give the big speech. It doesn’t really matter who.

The point is, what would you want all those people to say?

“About me?” says Oprah.

Yes, about you. What would you – Oprah Winfrey – want people to say about the life you’ve lived?

Oprah pauses and it’s a long pause.

“That she saw me,” she says, finally. “That she saw me.

She heard me. What I did and what I said mattered to her.

That is what I want them to say.”

A version of this article first appeared in the October 2015 issue of The Australian Women’s Weekly magazine.

VIDEO: Elizabeth Banks talks about surrogacy