In the red-dirt landscape of the Pilbara, local Thalanyji artists paint from above, as creation spirits – eyes in the sky looking over their children below.

Gazing down today from our little Cessna, the terrain looks as alien as the surface of Mars, yet few places on Earth feel as Australian. Mountain ranges ripple like muscles and ancient watercourses spider across the land. In the middle of it all is an unlikely oasis: Minderoo Station, home to Nicola Forrest, Australia’s greatest philanthropist.

Minderoo means ‘place of clean, permanent water’ in Thalanyji, and the Forrests have been a presence here since 1878 when brothers Alexander, David and John staked 960,000 hectares on the Ashburton River. Today David’s great-great grandson, the mining magnate Andrew “Twiggy” Forrest, owns it but Nicola, his wife of 30 years, runs it.

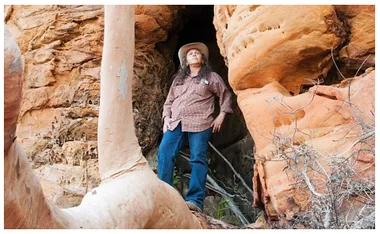

When she appears, it’s with sleeves rolled up and hair swept back. Nicola Forrest, 60, is diminutive in stature, formidable in presence. She holds my gaze, weighs our handshake and smiles with her eyes. Despite the wealth, she doesn’t scream money. Her voice is rich, her laugh earthy. There’s no stylist within cooee here. Nicola wears her daughter’s dress, her son’s wide-brim hat and her own dusty R.M. Williams’ boots. Ours is a rare interview.

“I’ve always dodged the spotlight,” she soon confides, munching on cold Vegemite toast. “It was fantastic to have the freedom to just be me. But our country is facing some intractable problems and we can’t just walk away. I’m passionate about the causes we support and believe they can resonate if we make change. But we can’t do it on our own. That’s why I’ve found my voice.”

Until recently Nicola Forrest was happy in the shadow of her larger-than-life husband as he hogged headlines with his iron-ore dividends ($2 billion last year from his 36 per cent share of Fortescue Metals Group), corporate acquisitions (the Forrests bought RM Williams for $200 million last October) and green-energy visions (Andrew has plans to build a hydrogen steel plant in the Pilbara powered by solar and wind).

But this is a partnership and ‘Nic and Twiggy’ make a dynamic duo, particularly where philanthropy is concerned.

“With their kind of wealth there’s no pressure on them to step up,” says former South Australian Premier Jay Weatherill. “Yet Nicola and Andrew are serious about tackling injustice and making a difference.”

Indeed, sometimes you can’t see the Forrests for the dreams. If it’s not curing cancer (Forrest Research Foundation) or eliminating slavery (Walk Free, of which their daughter Grace is founder-CEO), it’s ending disparity for Indigenous youth (Generation One), campaigning for affordable early childhood learning (Thrive by Five) or supporting creatives crushed by the pandemic (Minderoo Foundation Artist Fund). And there are dozens more behind the scenes. The pair made headlines in 2017 by announcing a massive $400 million in combined donations.

In March, Nicola’s ‘Open Letter To The Prime Minister’ demanded the government make a $60 billion investment to address “Australia’s gender crisis”. Counter-signed by Nicola’s allies, Marcia Langton, Rosie Batty, Lucy Turnbull and Ita Buttrose, it helped trigger a $3.4 billion investment in women in the May budget.

And that’s just the start. With a Forbes-estimated $20 billion war chest to invest in causes close to her and Andrew’s hearts, Nicola is suddenly on the frontline.

And as she tells The Weekly, at least some of that good work in the world has been inspired by heartbreaking events close to home.

“I’m passionate about the causes we support and believe they can resonate if we make change.” Nicola on the causes she and her family support.

(Frances Andrijich)The drought has broken at Minderoo and the Pilbara’s famous oxide-rich Pindan soil has flowered. Bush curlew and heron pick among the marshes, brown kites wheel overhead and the horizon is streaked with pink as galahs screech by. After four years of dry, 2021 has brought four months of rain.

A drought of sorts has broken in Nicola Forrest, too. She’s crying. We’re only 10 minutes into The Weekly’s interview, seated at the kitchen table that she normally shares with Andrew, 59, daughters Grace, 27, Sophia, 25, son Sydney, 20, and their Indigenous goddaughter Violet, 11 … plus the occasional wayfaring stranger like me.

At first it was a single, salty tear that broke free, despite madly batting lashes. Now tiny streams are running down her cheeks. What’s triggered this outpouring is a memory of childhood – the dusty winding track to the cottage her father, Tony, built for Nicola, her two older sisters, a younger brother and their mother, sculptor and matriarch Brooke Maurice, now 82.

“I dream about that road,” says Nicola. “A few years ago I went back to Spicers Creek with Mum for a school reunion. I had the same teacher and classroom my entire primary school life. It was such a joy … That road home is indelibly printed with memories of an idyllic childhood on the farm.”

Spicers Creek is a hamlet in NSW between Mudgee and Dubbo. Here the Maurice clan ran sheep and cattle and raised wheat.

“Nicola was a very bold and determined child,” recalls oldest friend Susie McPherson. “As a nine-year-old she’d jump on her pony Peggy and ride bareback for five kilometres to our farm. She was creative, too. Her home was full of books and art and orphan baby kangaroos hanging in old swags, with huge vegie gardens growing in hay bales out back.”

Although Nicola learned to muster from the back of her Dad’s motorbike, her preferred horsepower was Cannonball (“my best friend”), whom she rode to school each day.

At Minderoo, watching Nicola nuzzling Detonator, her favourite stallion, it’s clear the old kinship remains.

“Knowing animals gifts you an empathy for working with people,” she reckons. “Animals pick up on our nerves and need our trust. They have an intrinsic understanding of life that human beings don’t.”

Minderoo station co-manager Hamish Lee-Warner sees it too and tips his Stetson to her.

“Nicola’s bloody good on a horse, a crack shot from the chopper and as down-to-earth a sheila as you’d hope to meet,” he tells The Weekly.

Maybe it’s because she’s known struggle. At 12, when money got tight, Nicola’s father left home to work as a contract harvester and creativity became a more dependable currency.

“Mum was an artist, very good at painting portraits, often exhibiting. When Dad welded her a pottery wheel from old parts, she became a great sculptor.”

Brooke’s influence endures in Nicola’s love of art. Minderoo and the family homes in Cottesloe and Byford, near Perth, are dotted with works from Sculpture by the Sea, of which the Forrests are long-time patrons. And in this homestead, art is everywhere: Indigenous bark paintings, old surveyor maps from Minderoo’s early days, two canvases by John Olsen, a recent visitor to the station, even a ragged Akubra from Andrew’s jackeroo days is hung artfully.

“As an artist I could only make mud pies,” Nicola laughs. “My creative side was cooking.”

“Knowing animals gifts you an empathy for working with people.”

(Frances Andrijich)Turning her back on a university scholarship in early childhood learning – a calling she’s re-embraced in her Thrive by Five Foundation – Nicola followed her passion for food to Europe.

“My first job was working for a family in North Yorkshire, cooking game. I even cooked for the Duke of Marlborough,” she says.

Back home, Nicola worked for Australian ‘royalty’: as private secretary to publishing doyenne Lady Mary Fairfax, and as chef for Lady Susan Renouf.

“I catered Lady Susan’s parties and brought tea in the china she liked,” Nicola laughs. “She was great fun, intelligent and so kind.”

It wasn’t all fine dining and ritzy canapes however. It was 1988, and Nicola was hitchhiking home from work (flipping burgers at the Blue Heeler Hotel in Kynuna, population 10, and famous as the town where Banjo Paterson conjured Waltzing Matilda) when she first laid eyes on a cocky stockbroker named Andrew Forrest.

“I had a fear of being bored,” Nicola reflects. “Andrew was so exciting. I’d never met anyone with more energy than him – I still haven’t.”

But the road to true love is rutted with wombat holes. A few months after their engagement, the well-heeled boots of her fiancé got frosty.

“Andrew realised he wasn’t ready and suggested we put it off,” Nicola confides. “I felt humiliated. Certainly I was disappointed. We’d had an engagement party and were about to send out invitations. So I said, ‘If you really want to put it off, how about we just call it off?’

“Andrew was shocked … I may have thrown the ring back at him!”

Nicola fled to Europe. “I was a mess,” she says. “I begged Andrew: ‘Please promise not to contact me’.” She grins. “It’s still the only time I’ve ever known him to do what I’ve asked.”

Several months passed before a tear-stained letter arrived.

“Andrew wrote to say he was coming over for a business trip,” she recalls. “I was working at the United Nations in Vienna as secretary to the Minister of Finance. I thought, ‘I’ve just got my life under control, don’t come and ruin everything’. But he came, and I took him into Prague by car. It was 23 years after the Warsaw Pact, the Russian tanks had just left and nothing had been restored yet. We drove through the country in a little car and on the way we faced our demons, unpacked all the baggage and realised we still loved each other … then he got down on one knee. Again.

“Ever since then, we’ve had the ‘Czechoslovakia Pact’ where we agree on a big decision and neither can go back and say, ‘You made me do that’. We’re equal partners in everything – as parents, in the business, with all the charities. We still make each other laugh. He’s a fantastic father, a great husband …” Nicola’s blue eyes are sparkling. “He’s my best friend.”

And to Andrew, Nicola is “my gorgeous life partner, my most regular and reliable port of call for advice, and the great stable force of our family … She is down-to-earth, heaps of fun and often mischievous. We started as great mates, then best mates and fell in love, and that hasn’t changed. I love and admire so many things about Nicola.”

“My gorgeous life partner, my most regular and reliable port of call for advice, and the great stable force of our family.” Nicola’s husband, Andrew, speaking about his wife.

(Frances Andrijich)After our interview, Andrew FaceTimes her – “G’day Princess …” – from the US, on the second leg of a tour shirt-fronting world leaders on the benefits of green hydrogen.

On the first leg last year, he visited almost 50 countries and caught COVID on the way. He was medivac’d out of Croatia into Switzerland on a respirator.

Even as he recovered, his money never slept. The iron-ore company Andrew created in 2003, Fortescue, is the behemoth engine of the Forrest’s philanthropy empire, generating US$940 million on average every month. (It also produces two million tonnes of greenhouse gases every year – hence the couple’s zeal for zero-emissions energy).

“It’s crazy but only in the last few years has that money felt real,” Nicola says. “My own childhood taught me that money doesn’t buy happiness – most of the best creative decisions are made under restrictions. So yes, we took the kids to Bali and the south of France but we made sure they saw the slums in Brazil and India, too. Today it’s their humility and empathy that makes me proudest of my kids.”

Grace may tease her mum for washing and reusing zip-lock bags but her frugality comes from growing up with bugger-all, then losing it. Debt forced both Nicola and Andrew’s parents from their homes. Each was able to recover – Nicola’s uncle bought out the family farm and Andrew bought back Minderoo Station in 2009 – but the hard years left scars.

“Andrew loves talking of ‘snatching victory from the jaws of defeat’,” Nicola says, smiling. “Before he’d made his first million, he’d say, ‘I want to make 50 million and give most of it away.’ In 2001, when Anaconda Nickel struggled and he was booted out of the company he’d created, it tore us to the core. We had to mortgage the house and move out and a lot of friends and family lost money. It was horrible. But with the payout, a phoenix rose out of the ashes and that was the Foundation.”

Money seeded the Minderoo Foundation but Matilda Forrest – tragically stillborn that same year – is the charity’s guiding spirit.

“It was a complete shock,” Nicola remembers, taking a deep breath. “Matilda was number three so we’d found out the sex, chosen her name and imagined her life. And she was my biggest, with nothing physically wrong with her.” She lets the tears fall. “But I learned that sometimes there are no reasons, no answers and no consolation.

“We got through the birth. There was a service. The girls came in, held her. Andrew’s not afraid to go to the hard places but he was a mess. Of course I blamed myself. I felt anger, confusion. People would avoid me afterwards, cross the road rather than talk to me. I learned how common stillbirth is – six babies are stillborn in Australia every day – and how little it’s talked about. That was an epiphany. So many women with so much unresolved grief. It’s why today I try to be brave and talk about it.”

“I learned that sometimes there are no reasons, no answers and no consolation.” Nicola speaking about the tragic stillbirth of her daughter.

(Frances Andrijich)Like the dry red dirt that flowers under her feet, Nicola alchemised the tragedy into triumph. Her Thrive By Five passion project fights for accessible, affordable early childhood learning for all children.

“The first five years are crucial,” she enthuses. “It’s when 90 per cent of the brain develops and millions of neural connections are made. It’s when the light of opportunity shines brightest in a child’s eyes.”

This is Nicola’s calling and has been since her Spicers Creek days, says old pal Susie.

“In a school as small as ours, the older kids teach the younger ones. Nicola was brilliant at it – she’s always been a leader and a carer with great ideas.”

Jay Weatherill, Thrive by Five’s CEO, concurs.

“Nicola is charming, determined and empathetic but her vulnerability is why she connects so widely,” he says. “The pain of Matilda’s loss will never leave her. But it drives her too. That’s why she’s never going to stop campaigning until there’s a total reimagining of early childhood education in this country.”

Back in the paddocks, Nicola Forrest leaps into action.

“I’ve got ants in my pants!” she hoots, jumping off an anthill into the saddle to herd a few of Minderoo’s 15,000 Droughtmaster and Shorthorn cattle. Out of the spotlight and into the dust, Nicola leads the herd out, a red cloud rising in her wake, her grin as wide as the Pilbara horizon.

“I turned 60 in January and it’s given me a great chance to reflect,” she muses that night, over a humble bowl of beef stew and mash. “I’ve loved every stage of my life. There have been ups and downs but really life just gets better. I try to make the most of what life has given me by giving to others, creating opportunity and making change.

“My father told me: ‘When the chips are down, heroes rise’.” Nicola looks up and I see a glint, but this time it’s steel in her eyes, not tears. “Usually it’s the most unlikely person who finds the courage to try.”

Read more in the August issue of The Australian Women’s Weekly on sale now.