Everyone was in their pristine tennis whites at the Albury Tennis Club when an Aboriginal man with a cigarette in his hand and a fedora on his head walked across the back of the court.

Following him was an Aboriginal woman with a pram and six children walking in a row.

“All the people who were playing just stopped,” says Evonne Goolagong Cawley.

The Goolagong family had come to see their prodigy play but they didn’t know much about tennis – or it’s etiquette. “They didn’t realise they were on the court.”

Later her father, Kenny, a gun shearer and a Wiradjuri man put his fingers in his mouth and loudly whistled her.

“And I heard him,” Evonne shrieks with laughter, “and I came.”

A lifetime later, we are in an elegant street in Noosa, where there are grand Mediterranean houses with terracotta roofs, streets lined with neatly trimmed box hedges and lush tropical gardens tended by flocks of gardeners.

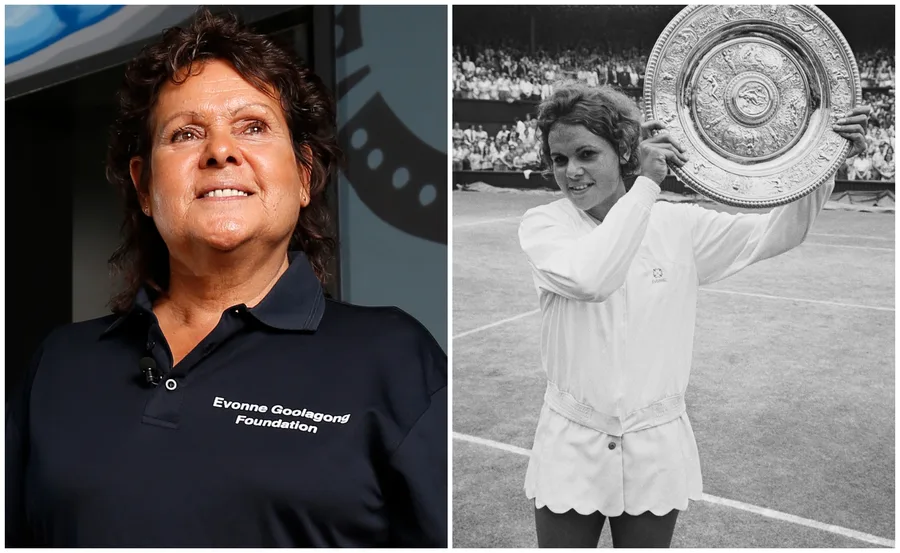

And there is that face, that famous face. It is a face that is etched into the national consciousness, part of the story of Australia: The humble Aboriginal girl from a tiny country town who, against all the odds, became the number one tennis player in the world. And did it with grace and humility; a symbol of hope for her people and pride for her country.

Evonne was only 19 when she first won Wimbledon in 1971 against her hero Margaret Court. Overnight she became a superstar. She has told the story many times of how, as a nine-year-old, she read a story in Princess magazine about a girl who was found and trained and taken to this place called Wimbledon where she played on this magical centre court and won.

When Evonne found out that Wimbledon was a real place in England, “every time I hit the ball after that I would pretend I was there”.

Through the homesickness of an adolescence away from her family, “every night I’d go to sleep dreaming of playing on that magical centre court. Today they call it visualisation.”

Evonne Goolagong Cawley remains an Australian legend and icon of tennis.

(Getty)On the historic walk to that fabled centre court in 1971, she saw, written above the doorway, the famous quote from Rudyard Kipling’s poem If: ‘If you can meet with triumph and disaster and treat these two impostors just the same.’

“I remember thinking,” says Evonne, “oh, my mum and this man Rudyard would have gotten on very well.”

Her mother Linda was a religious woman, unable to read or write, who had sung her eight children to sleep with hymns.

“She was a very moral person, I never heard anyone in my family swear,” Evonne recalls now.

Linda famously made Evonne’s first tennis dress from an old bed sheet.

“It was lovely and soft and she made it perfect, with plenty of room to move. And it was white because she boiled everything.”

Her idea to paint Evonne’s shoes white with the lines marker from the tennis courts didn’t work quite as well. “They would crack halfway through the day,” she chuckles.

Today, at 69, Evonne is still that artless brown-eyed girl who captivated the world – warm, vivacious, lively, exuberant – as she looks back down the decades of her unexpected life.

In this third act, her passions are her grandchildren Beau, Lucy and Theodore, and the Evonne Goolagong Foundation which gives opportunities to Indigenous children to help them be the “best that they can be by staying in school”.

In its 17 years, the Foundation has put 74 children through the best schools in the country and produced doctors, teachers, lawyers.

When Evonne was at school, she once wrote an essay saying that white farmers tended their sheep, smoked their tobacco and shot Aboriginal people who came onto their land. That had been her experience of the world.

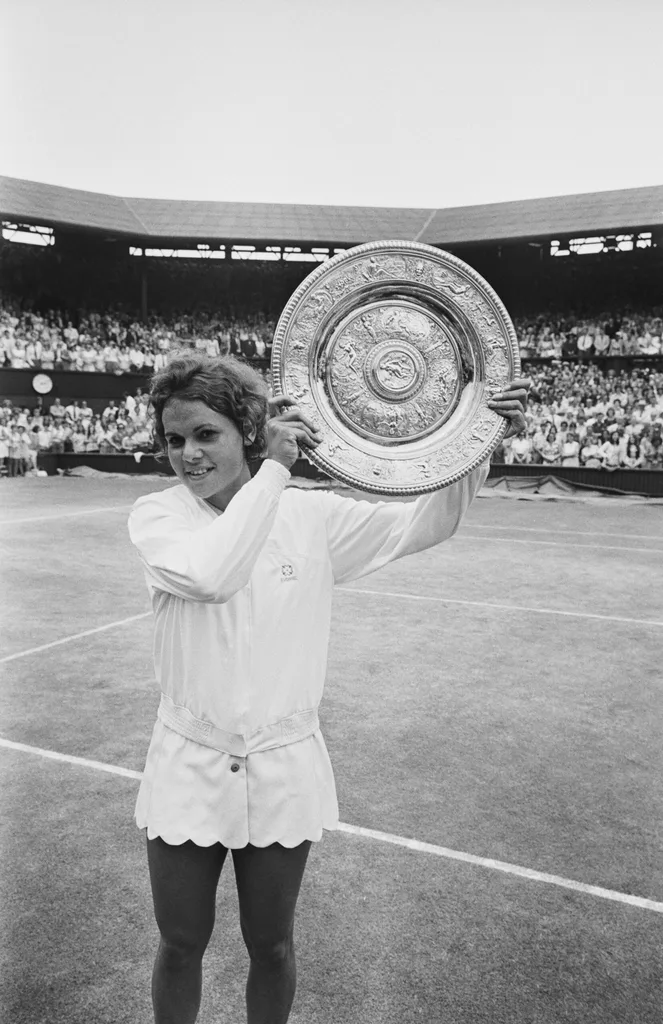

Evonne took out the Wimbledon Women’s Singles title in 1971.

(Getty)Yet Evonne went on to become Australian of the year, to pick up an MBE, become an Officer of the Order of Australia and more recently Companion of the Order of Australia, to be inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame.

She won 14 Grand Slam tournament titles: seven in singles (four at the Australian Open, two at Wimbledon and one at the French Open), six in women’s doubles, and one in mixed doubles. She won the Fed Cup title in 1971, ’73 and ’74. And she was singing while she did it.

Chris Evert has said that, before a final match, she would be quiet, serious, focused on the task ahead, and in would come Evonne singing away.

“Well, I was the first one to take music into the dressing room. It was a transistor first and then a tape recorder.”

She was mainly in a soul music groove when she was slaying people on the tennis courts of the world: “Otis Redding, Tina Turner – I just love music.”

When she won Wimbledon for the second time in 1980, she was the first mother to do so since Dorothea Chambers in 1914. Her daughter Kelly was three.

Plagued by injuries and then “really sick” with “iron-poor blood”, she and her husband, Roger Cawley, were only there because they had already paid a large deposit on a rented house.

“She didn’t think she could play,” says Roger. But then she started feeling better. It was the wettest Wimbledon on record but it seemed the sun always shone on Evonne, and she earned the name Sunshine Supergirl as a result.

A former junior tennis player, Roger had been her training partner since they married in 1975 because “I could hit the ball very forcefully, even though she’s 20 times the player.”

Evonne and Roger had met when she arrived in London in 1970. She was a touring player, travelling the circuit, so “I wrote her millions of letters. It took me five years to persuade her to marry me,” he says.

They made up for it though with three weddings. The first was discreet, in a registry office in London.

The second at home in Barellan, NSW, where hundreds of people turned up to a church that only held 35.

“Everyone brought a plate and the party went on all night,” recalls an amused Roger.

By the third renewing of vows, they were running with a fast celebrity crowd. It took place in Elvis’s room at a Las Vegas country club. Glen Campbell, dressed only in tiny shorts, was best man. John Denver was a guest.

Evonne and Roger, pictured in 1975.

(Getty)They went on to have two children: Kelly, born in 1977, and Morgan, in 1981.

Throughout those years, under enormous pressure as both a mother and a champion, “Evonne never complained,” says Roger. “Nothing used to bother her.”

In 1978 she snapped a calf muscle playing Martina Navratilova in the Wimbledon semi-final. “She didn’t give up, she didn’t walk off the court.”

“I don’t get upset,” Evonne says now. “It is too much of a waste of energy, it’s too tiring.” But in her 1993 memoir Home, she gave it some more thought: “I would wonder why people got so upset when they lost, surely it didn’t matter that much. Why couldn’t I get mad at my opponents the way my coach Vic Edwards wanted me to?”

She concluded that “the way I played the game reflected a calmness, a serenity of spirit, which I now equate with being Aboriginal.”

When Evonne was a small child, the family used to stay with relatives at a mission in Griffith. Whenever a shiny car came down the road, Evonne’s mother would say: “‘You’d better run and hide, the welfare man will come and take you away.’ So I used to hide under the bed.”

Part of the legend of Evonne Goolagong is that, from an early age and using the handle of an apple crate, she would hit “an old moth-eaten ball Dad found” against a wall.

“I’d count how many times that ball hit the wall without making a mistake. I would write the highest score in the dirt and come back the next day and try and beat that score.”

Right next door was the Barellan War Memorial Club with tennis courts attached.

“From the back fence, you could hear the tennis balls – thwack, thwack, thwack.”

The club president Bill Kurtzman had seen the little girl – surrounded by chickens, dogs and wrecked cars – whacking the ball against the wall and peering through the fence.

He invited her to join and put her in the coaching school even though, at six, she was too young.

“In those days,” she recalls, “Aboriginals weren’t allowed in clubs anywhere.”

Evonne pictured with her coach, Vic Edwards.

(Getty)Bill would drive her to matches and, with locals Dot and Clarrie Irwin, took the hat around town to raise enough money to get her on the plane to Sydney for training and to buy the clothes and equipment she needed.

It was kindness she has never forgotten and which drives her own work with Indigenous children: “I wanted to do what the townspeople did for me. Otherwise I wouldn’t be here in the first place, you know.”

Sydney tennis coach Vic Edwards heard about the prodigy and drove to see her. He persuaded her parents to let him take the 14-year-old to Sydney to go to Willoughby Girls High School, board with his family and be coached by him.

Shy and scared, night after night she cried herself to sleep with homesickness but didn’t want to upset her parents by telling them. She knew what she wanted – that magical centre court – and when she was playing tennis she felt as if “nobody could touch me. I was in my own world”.

Evonne was soon winning matches all over the state. She would often play doubles with Vic’s daughter, Patricia.

“We were playing these two older ladies and one of them didn’t like the idea that two younger girls beat up on them so badly.

When it was time to shake my hand, she said, ‘Oh, this is the first time I’ve had the pleasure of playing against a nigger.'”

Evonne was so stunned she just stood there. And then she got upset, “really upset”, and with her newfound confidence, she complained to the Department of Aboriginal Affairs.

Then she took on the world, and became one of the greats, revered everywhere she went. It can take ages to do the grocery shopping, Roger says, because she is still so loved and “so approachable. Everyone wants to stop and have a chat.”

Evonne was a magnificent athlete, known for her grace, for being poetry in motion.

“She’s very quick,” says Roger, “naturally fast. You wouldn’t notice it because she moves so beautifully, she glides. You can’t take your eyes off her.”

Her opponents could get caught up in a ruthless ballet. Billie Jean King became so engrossed watching her that she forgot to hit the ball.

“She was like a panther compared to me,” Billie Jean said after losing to her in 1974.

What they were watching was sheer joy.

“Every time I played, it was like a celebration,” she explains.

“I just enjoy playing tennis. I even loved the training. I felt very lucky to be there: lucky to be found by the townspeople of Barellan who helped me all the way through; lucky not to be taken away [with] the stolen generation. I would just think, ‘Wow how lucky am I?'”

Evonne was a tennis powerhouse.

(Getty)Sometimes she was so absorbed in the game that she came off the court not knowing if she’d won or lost, as she did at Wimbledon in 1980.

“She lost three Wimbledon finals and I guarantee anybody seeing her ten minutes after would have no idea whether she’d won or lost,” says Roger. “And the same on the occasions she won.”

There are remarkable similarities in temperament and perspective between Evonne and Ash Barty who, 50 years later, tells The Weekly she is the next Indigenous person determined to win Wimbledon. “This is the first time I have said it out loud,” she admits.

“There are certainly matches where I’ve come off the court a lot happier when I’ve lost and sometimes not quite so happy when I have won,” she adds, pondering her similarities to her friend and mentor.

“It’s more about the effort and the competition and the challenge. That’s what we love the most, regardless of the actual result: that moment in time, the challenge that brings out the best in you. I think, throughout Evonne’s career, that’s certainly been true. Looking back at those matches, you can see in her face that she just loved playing. I think that’s one of the true meanings of sport, and I think Evonne is one of the first to really encapsulate that.”

Ash began to appreciate the significance of Evonne’s career when she was in her late teens.

“It was all the more special getting to know her,” she says. “That was remarkable. She treated me as an equal, and now I’m very lucky to be able to call her a friend. She is only ever a phone call away. She’s been through the same phases and feelings that I’m going through, and I know if I need that shoulder to lean on she is always there.”

When Ash became overwhelmed in 2014, she turned to Evonne, who told her to “drop a line”, go fishing, take a break – that there is more to life than tennis.

“It was a reinforcement – to make sure I was happy, to find out what my real passion was, the true love, and to find the drive again. And, you know, it took some time – I went the squiggly way around I think – but it has all led me to this point in my life. Every day I try to learn from her career.”

Evonne became Ash Barty’s mentor in later years.

(Getty)When injuries forced Evonne into retirement in 1983, she and Roger lived in South Carolina, where she was the touring professional for the Hilton Head Racquet Club.

They bought land and had business interests, and they ran with a fast, famous crowd. The singer Kenny Rogers was their best friend, Roger discussed using jelly beans for giving up smoking with Ronald Reagan on two visits to the White House.

Their celebrity social set, says Roger, helped them to raise funds for the things Evonne cared about. “I did a lot of charity events,” she explains – some with Ethel Kennedy, the widow of Bobby.

Later, a cousin who was doing a family tree found that the brother of the patriarch, Joe Kennedy, was a relative on Evonne’s mother’s side.

He had come to Australia from Ireland when his brother moved to America. “I always wanted to go up and knock on the door and say, ‘Hey, I’m your cuz,'” she jokes.

Evonne’s father, Kenny, died at 44. He was killed in a hit and run incident. Evonne was devastated. It was her coach, Vic Edwards’ refusal to let her go to the funeral – his insistence she stay and play the match against Billie Jean – that caused their final ugly split.

“Mr Edwards tried to take advantage of me physically, mentally and financially,” she says diplomatically now.

In her book she hinted that he had sexually harassed her.

Even before they married, Evonne had told Roger that one day she would go home. In those years away she had written to her family every week, and they had kept suitcases full of articles about her. She had also bought her parents a house. The death of her mother in 1991 – and the funeral at which she met relatives who she had never known – fired her determination to explore her Aboriginality.

“I really wanted to find out: what exactly is Aboriginality?” she says now.

She had been so young when she had been taken into a white middle class world that she had never known what it meant to be a Wiradjuri woman, or Aboriginal or even what her success had meant to her people. There were 60,000 years of culture to get acquainted with.

She had bought books and tapes and shown them to her children but “I didn’t have a history until I found out about my family,” she says.

“I wanted something to pass down to my kids so that they would have a history to pass down to theirs. To me, it is probably the best thing that has ever happened to me.”

In 1999, Evonne spent three nights in the desert with women from Mutitjulu, in the shadow of Uluru, doing women’s business.

“We connected to the Seven Sisters Dreaming. I had an amazing experience there and all the women were laughing at my expression of what I was going through,” she says.

Writer Phil Jarratt worked with Evonne on her book Home, which recounts this part of her journey.

“Evonne spent over a year doing the research,” he explains, “tracking down her family in western NSW, going to places, meeting people whose lives had played out very simply. She saw flashes of the life her parents had had. It regenerated her identity and probably ultimately led to what she has done in later life.”

Since then, Evonne has worked tirelessly to give back to community and country. She speaks with pride of the young people who she’s supported through the Evonne Goolagong Foundation, and who are family to her and Roger.

Connecting with her Aboriginality has been absolutely crucial to the second half of Evonne’s life. She could have gone through life in enclaves of wealth in America, living on her reputation, but she didn’t.

She came home, found out who she really was, and gave so much back. And that in turn has brought her the happiness that is so transparent in her every word and gesture.

In 2020, during NAIDOC Week, Evonne jotted down some thoughts about the pride she feels as a First Nations woman, and her hope for a path towards reconciliation. It would mean the world to her, she says, if we would publish it in The Weekly

“For me, our elders past and present were and forever will be, not just the caretakers of our country for 65,000 years, but the true heart and soul of it. And for that I am truly proud. We need to share their great knowledge with all Australians. Education is the key. The more we learn from each other, the more there will be true reconciliation in this country. We need to hear their story. It’s time our First Peoples were included in our constitution.”