As we wander through the subtropical rainforests of Springbrook National Park on Queensland’s Gold Coast, it’s impossible not to be awestruck by the sheer majesty of the scenery.

These forests are living relics from the Jurassic Age and their 1800 million-year-old Hoop Pines, trunks scored with banded bark, emanate an ancient wisdom that reaches into your soul.

For Dame Quentin Bryce, this is a place of renewal and wonder. She immerses herself in the unique aura of tranquillity that only nature can provide, and finds solace amid the giant mossy rocks, shimmering luminous fungi and dreamy tapestry of towering trees, bright green ferns, and hanging vines and lianas.

For Dame Quentin, Springbrook National Park is a place of renewal and wonder.

(Photo: Corrie Bond)Quentin, now 79, played here as a child, she and husband Michael brought their own five children to the cascading waterfalls, and when the couple moved back to Brisbane in 2014 at the end of Quentin’s Governor-General tenure, they regularly came to the mountains for bush walks.

“The atmosphere, the swirling mist and what the rainforest does when you step under that canopy is special,” Quentin tells me as she strokes the trunk of a 3000-year-old Antarctic beech tree.

“It’s a source of great happiness in my earliest childhood memories because we used to have our holidays at Surfers Paradise when we were kids. It was sun and sand and beach, the beauty of that part of our world. But if it was a bit of a dull day, or we needed a bit of a change, we’d go up to Tamborine and to Springbrook and the rainforest. When my parents were old, they lived at Tamborine and my dad used to take our children, when they were little, on walks through the rainforest. It is absolutely magic!”

Quentin chose this place for The Weekly’s photo shoot, not just because of those bygone days, but also because it features in William (Bill) Robinson’s masterpieces of the area, paintings she collated for an exhibition she was curating when Michael became critically ill.

“For a lot of Brisbane people, it’s part of our lives, going to the rainforests. When you move up from the coast and drive up to the mountains, you go into this different atmosphere, and the way Bill has brought that to his canvasses, those great trees … he captures that perfectly. I notice the way when we have little ones there [Quentin’s 12 grandchildren regularly continue the family pilgrimage] how, as they step in under the canopy, it changes them. A calmness, yes. So much to see. It’s always beautiful. It can be a day when there are showers and mist and then it clears and you see the light dappling through those leaves. It’s where rainforest meets the ocean. We can’t see out to the ocean from up here today because of this most wondrous fog, which is also sublime.”

As Michael battled cancer and endured the necessary caravan of hospital stays and treatments, he and Quentin lost themselves in the great outdoor world of Queensland’s rainforests through William Robinson’s magnificent landscapes.

Nature helped Dame Quentin and Michael during his illness.

(Photo: Corrie Bond)While Quentin tracked down Bill’s most famous works, many on loan from private owners, and planned the exhibition for HOTA – Home of the Arts, the Gold Coast’s impressive new art gallery – she leaned heavily on Michael.

Quentin was the rookie here, she tells me. She certainly appreciates art enormously, but she’s no expert and Michael, a much-feted architect and designer, became her touchstone for advice and ideas.

Together they also spent halcyon hours with Bill, a time she now looks back on with immense fondness.

Planning the exhibition proved the perfect antidote to the medical mire that could at times engulf them.

And then after Michael’s death, Quentin continued to work on the beautiful catalogue and the Lyrical Landscapes opening day which happened at the end of July last year, something that she says helped her navigate her grief.

“It was a wonderful thing for me last year, and also through that time the year before – having a distraction in my life which was all about the art and beauty that was so important to Michael, that signified a great part of his life, that he taught me so much about. That was a huge help.

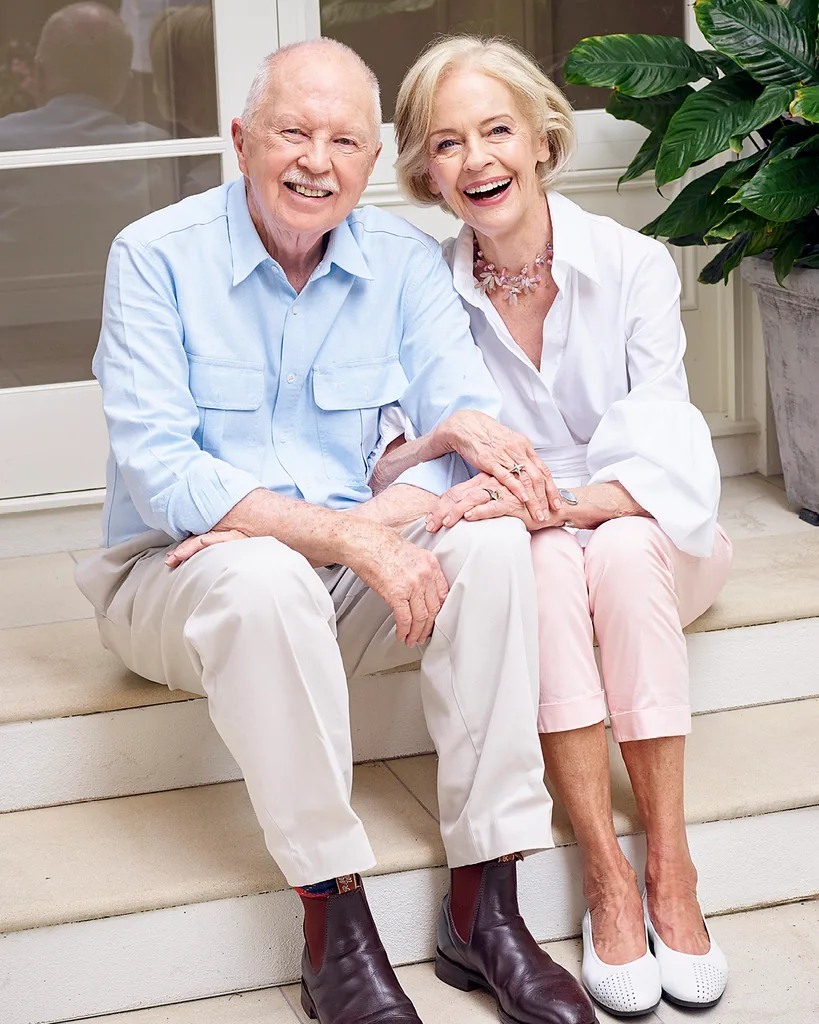

Dame Quentin and her beloved husband, Michael.

(Photo: Supplied and used with permission)“Michael and I loved Bill’s work – a truly great Australian painter. I was so honoured to be bringing together these works of the master of landscape painting. That brought a joy. Michael and I talked about that a lot and certainly it emphasised to me again and again how wondrous and healing art and beauty is, the great beauty of our environment. How significant that is.”

The lush colours of Robinson’s paintings are deliberately echoed in Quentin’s outfits for The Weekly’s shoot, and as we pull up in a car park for a quick clothing change, Quentin breaks into a huge smile, delighted to spy a sign for the endangered Herbert River ringtail possum.

“Michael designed that in 1974 when he moved from architecture into graphic design,” she shares proudly. “He designed all the Queensland National Park signage and this is one of his most well-known logos. It’s lovely to see the possum is still alive and so is Michael’s sign.”

The day after our sojourn to the mountains, we settle down to talk in Quentin and Michael’s Brisbane home, an oasis of calm.

The last time I was here, Michael was making me lunch and recalling his first date with Quentin in 1962.

“Afterwards I couldn’t think of anything else,” he said. “It just obsessed my life, wanting to see her.”

Theirs was a powerful love match and the void he has left is immense.

“The house is full of him,” says Quentin. “I don’t talk to him, but I talk of him. The little grandchildren talk about him, too, even Sylvie, who’s four now and was a huge source of joy to Michael. I see her back then at two, climbing up on him. He’s sitting out the front of the house having a cup of tea. She was too heavy for him to lift, but she could climb up and get the pen out of his pocket and pull his glasses out. Anything she did, he’d say she was a genius. She’d then go and pick flowers out of the garden and hand them to him.

“I don’t talk to him, but I talk of him.” Dame Quentin speaking about her late husband.

(Photo: Corrie Bond)“It’s taken her a while, but now it’s quite clear in her mind that he’s not here anymore and he won’t be coming back. I don’t know how her parents talked to her about that, but I find it uplifting, this understanding she has, because when he first died she’d come running down the hallway calling, ‘Where’s Pop Pop, where’s Pop Pop?’. For her, so young, coming to terms with this change and loss, it’s something that a very big family like ours shares.

“I think, too, of Alexandra, our eldest grandchild, who spent a lot of time here with her grandfather. She’s 22 now and heading off overseas, and I can’t help but feel overwhelming waves of sadness. We say, ‘What would Pop Pop say about that?'”

Michael’s decline coincided with the spread of coronavirus, and all at once it seemed like everything was changing for the Bryce family and a growing anxiety set in.

“The uncertainty and confusion and the whole unknown-ness of our lives, for all of us in the country, was hard, and of course it had a differential impact on people like Michael, who were vulnerable.

“I remember I was planning to go to New York, which I’m actually rescheduling now, to give the Anzac Day address for the American Australian Association in one of the oldest churches in the city. I’d been in two minds about it for a while, because Michael was becoming really quite ill, but I remember, too, that I cancelled the trip after speaking to former US ambassador John Berry on the phone. He said that as he was talking to me he was looking out of his window in New York and all he could see in his street were coffins.”

Dame Quentin never let herself imagine a life without Michael.

(Photo: Corrie Bond)Suddenly, the Bryces’ lives turned into a muddle of worrying days and furious visits to specialists. Through it all Quentin admits she never allowed herself to imagine that Michael wouldn’t make it.

“He’d go to hospital and have treatment and come home, and then something would happen so he’d be back in hospital, for tests or from a fall or some incident and then rehab. But we were always very optimistic and he was, too, that this would extend his life, that this was going to be of much more benefit than actually happened.

“Then amid the busyness of it all, there was the overlay of the pandemic, of periods when we couldn’t see the children and the little ones. I can remember in the early days of the first lockdown in Brisbane, we’d sit on the front steps and the gate would be closed and the children would be outside on a rug on the lawn and I’d read to them.”

The trepidation of waiting for Michael’s results was extreme, and as a coping mechanism Quentin would head into her office at Queensland University of Technology and bury her head in work.

“I suppose it was my respite care,” she says with a smile. “Work can be a wonderful distraction and focus that enables you to switch off. I remember when Tom, our youngest, was very ill as a little boy, that’s when I would go to work. I would just switch off the anxiety about Tom, be away for as short a time as possible and have a break from it.”

“It was the most important thing in my life, my marriage”

(Photo: Corrie Bond)Also helping to keep up spirits were friends and neighbours in the community.

“A wonderful friend of mine would ring and say, ‘I want to make a chicken drop.’ She would bring it all wrapped up in heavy rolls of Alfoil, a chicken out of the oven with a lot of roast vegetables. Michael used to say it was the best chicken he’d ever eaten. She is a wonderful cook!

“What shines through as I look back on that time was the kindness of friends and neighbours, and how lucky we were to have some of our family close by, particularly our son Tom, his wife Lucy and their little boy Charlie, who live just up the road.

“All those appointments and waiting for results, it’s what preoccupies you, but there’s a lot of things to learn about that you never expected to be learning. We’ve all had the experience in our families and friends of people going through these things and you observe it at a distance or maybe more closely, but nothing prepares you for it really.”

As weeks turned into months, Michael wasn’t improving.

WATCH: Dame Quentin Bryce poses for The Australian Women’s Weekly. Story continues after video.

“Anzac Day that year [2020] was especially memorable because there was no Anzac Day march in the city. That was always a very big thing in Michael’s life. He loved anything to do with the military. He was born in 1938 and his father had served in World War II so he belongs to that generation for whom Anzac Day is very special in so many ways. He knew so much military history. His study walls are lined with military history books and he was in the Air Force Reserve, in No. 23 Squadron; it was a very important part of his life.

“There was quite a lot of discussion about whether there would be the usual march, but it was cancelled. People marked Anzac Day in their driveways. I’ve got a lovely photograph of us all having our own little ceremony that Michael organised, saying the Ode and talking about Anzac Day in our driveway for our own dawn service. We went out in the dark and there was a young schoolboy there who played the bagpipes. Charlie, our little grandson, came too, and some of the family who lived nearby.

“But looking back I think of that as a marker of Michael’s growing frailty, because even if there had been an Anzac Day march, I think it probably would have been the first time he hadn’t been there.”

Despite his illness, Michael’s death at age 82 was a shock.

The family had gathered at eldest daughter Revy’s for an early Christmas lunch, and then on Christmas Day itself they went out to lunch with daughter-in-law Lucy’s family to a restaurant. Michael was frail but seemed good.

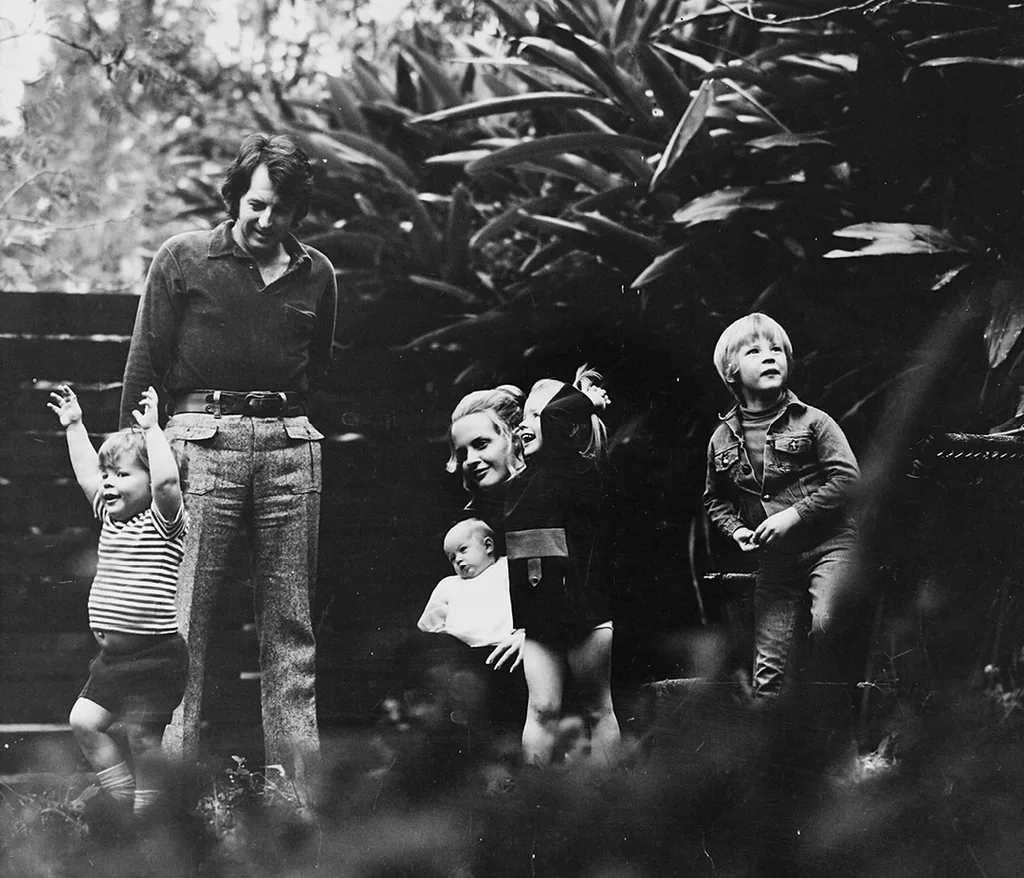

Dame Quentin, Michael and four of their five children.

(Photo: Supplied and used with permission)“It was just a couple of weeks later that Michael died,” sighs Quentin. “He had been in palliative care for a little while in hospital and then he came home. The final days were really about the family gathering.”

A beautiful funeral involving the whole family and especially the children and grandchildren was held at St John’s Cathedral in Brisbane.

“We were married there, and our children and grandchildren had their christenings there. Michael loved the cathedral. The day before, we found out that restrictions were being lifted and you could have 200 people, so we got busy and let people know. There was so much to do and it’s just all that momentum, really, that gives you the physical energy. You keep going.

“My darling family – I had to be very conscious of our children because Michael was truly an exceptional father. When I was writing the words for my farewell, I asked Tom, who dropped in, to have a look over it – meaning don’t change anything because I won’t do it. I’d thought about it very deeply. But I remember Tom saying, ‘I think you should say a little more there, Mum,’ and it was really about Michael as a father.

“He said, ‘Dad wasn’t a father who went to the pub or the club; he came home and cooked the dinner.’ And of course, that was so – we had a marriage that I suppose in a lot of ways was ahead of its time in terms of men and women’s roles. I spoke about that when I spoke of Michael, decision-making and translating the rhetoric of equality into reality.

Michael’s funeral was held in the same church that they were married.

(Photo: Getty Images)“I think he always expected me to have a career. I remember particularly when I was making a very big decision about going to Sydney to take up the role as Federal Sex Discrimination Commissioner, and talking about how would we do it with the children. Michael simply said to me, ‘Let’s give it a go’.”

What made Quentin and Michael click as a couple?

“I think really it was that we grew up together. We had a wonderful romance and then we were married when I was 21 and a law student. A very important thing in our marriage was going off to live in Europe when we were young, taking our little baby Michael, who was just a few months old – I can’t believe I did this – on a ship that took four weeks to get to England. Architects did that in those days. Off we went.

“I think it certainly made me grow up. The independence and the adventure of it, the world really. We just depended on each other. Living on a budget, sixpence, wonderful times …

“We were married for a long time. Not long after we came back to live in Brisbane from Canberra, we had our golden 50th wedding anniversary here in the house with lots of friends and family. It was the most important thing in my life, my marriage, the happiness and confidence and support, all those qualities that build a strong marriage and a very long togetherness.”

Now more than a year on from Michael’s death on January 15, 2021, Quentin confesses she’s finding the grief all-consuming.

“I think it’s something that as the year went on got harder. There are a lot of people around who care deeply. People say comforting things, and there are offers of generosity, kindness and thoughtfulness, but I think it’s a very isolating thing.

“Every now and then, you come across some words that stay in your mind. Deeply touching, inspiring words have been written about grief. I remember a phrase – ‘grief is the price of love’ – and I think it’s one that the Queen has used. I think it says a lot of things. It’s a very beautiful expression.”

As she enters a new stage in her life, Quentin is painfully aware that it’s the first time she has ever really been on her own.

“I remember my youngest sister, Helene, who lives in London, saying to me when I was going to Sydney to take up that job with the Human Rights Commission, ‘Ooh that’ll be a challenge for you, you’ve moved from cocoon to cocoon!’

“I remember a phrase – ‘grief is the price of love’ – and I think it’s one that the Queen has used. I think it says a lot of things. It’s a very beautiful expression.”

(Image: Getty)“She was right. I did. I was married at 21. I’d been at home, at boarding school, at university, and never really on my own. From cocoon to cocoon. But I’m so lucky that four of my five children and their families are in Brisbane. I see a lot of them and they’re interesting and exciting, there’s always new things coming. I love being part of their lives and learning from them, sharing their company, especially taking them now to concerts and the theatre.

“And just in the last few months, I’ve been thinking about the need for me to have structure in my life,” says Quentin.

She is planning some writing and work continues apace. She is also very aware of guarding her health.

“Quite a few years ago I took up yoga. I’m very conscious of keeping fit and well, being responsible about my health. I do Pilates three times a week and I swim. I love being in the water and I love to walk.”

And on the immediate horizon is also travel. “That trip to New York that was cancelled, I’ve been invited again this year so I hope I’ll be going in April.” I sense that Michael would definitely approve.

You can read this story and many others in the May issue of The Australian Women’s Weekly – on sale now

.jpg?resize=380%2C285)

-(3).jpg?resize=380%2C285)

.jpg?resize=380%2C285)