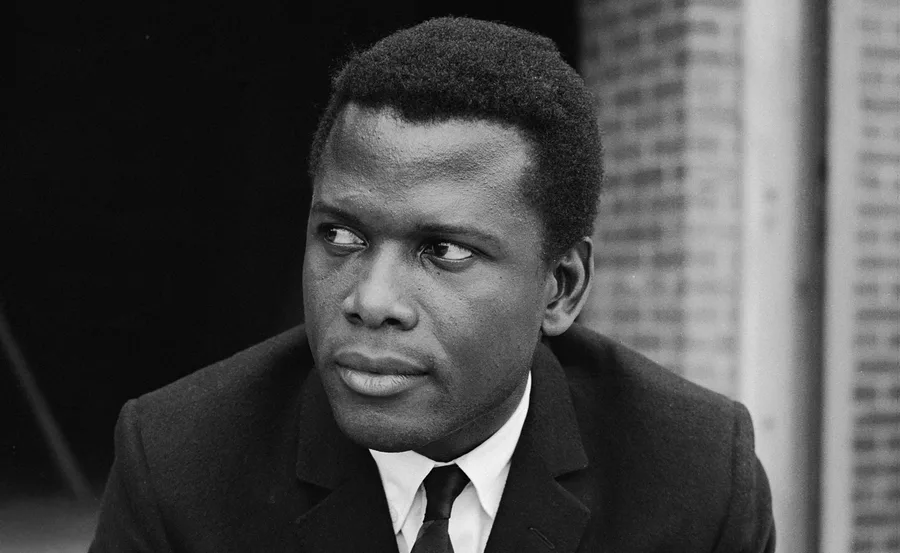

Sidney Poitier died on January 6, aged 94. In honour of his legacy, we’re republishing this piece from the March 2020 issue of The Australian Women’s Weekly Icons.

The year was 1967. As riots overran America’s cities in the midst of a time of extreme racial unrest, there was some irony in the fact that the biggest box-office star in the US was black.

In fact, actor Sidney Poitier was the star of three massive films that year – To Sir, with Love, In the Heat of the Night, and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner.

The epitome of Hollywood class and cool, Sidney was at the pinnacle of his success, having broken racial barriers that eventually others would follow him through.

But his journey to the top hadn’t been without a struggle, and being at the top wasn’t everything it seemed.

Sidney Poitier was the star of countless box-office hits, but being at the top wasn’t everything it seemed.

(Image: Getty)Born in 1927 in Miami, Florida, Sidney grew up in the small village of Cat Island, Bahamas, until his father, a tomato farmer, moved the family to the capital Nassau when the boy was 10.

It was here, as a youngster, that Sidney first discovered a love for cinema.

Moving to New York when he was just 16, he began working as a janitor for the American Negro Theatre in exchange for acting lessons.

Told that his accent was too strong, Sidney practised speaking along to the radio news, and finally made his stage debut as understudy for Harry Belafonte in the play Days of our Youth.

He continued to perform on stage until 1950, when he landed his first movie role as Dr. Luther Brooks, a black doctor who treats a bigoted white criminal, in No Way Out.

The movie established a pattern for the young actor – keen to refuse roles that played to racial stereotypes.

“It was difficult,” he told Oprah Winfrey in 2000. “[Black people] were so new in Hollywood. There as almost no frame of reference for us except as stereotypical, one-dimensional characters.”

More movies followed during the ’50s, including Blackboard Jungle (1955), Edge of the City (1957) and The Defiant Ones (1958).

Then, in 1963, came the role of Homer Smith in Lilies of the Field, which saw him win the Oscar – a first for an African-American man (Hattie McDaniel having won Best Supporting Actress for Gone with the Wind in 1940). It was a shock for Sidney.

“I guess I leaped six feet from my seat when my name was called,” he said later. “You can call that surprise if you want to.”

In 1963, came the role of Homer Smith in Lilies of the Field, which saw Poitier win an Oscar.

(Image: Getty)“In 1964, I was a little girl sitting on the linoleum floor of my mother’s house in Milwaukee watching Anne Bancroft present the Oscar for Best Actor at the 36th Academy Awards,” recalled Oprah.

“She opened the envelope and said five words that literally made history: ‘The winner is Sidney Poitier.’ Up to the stage came the most elegant man I had ever seen, I remember his tie was white, and of course his skin was black, and I had never seen a black man being celebrated like that.”

“I like to think it will help someone,” Sidney said at the time, when asked whether his win would move the rights of black actors forward.

“But I don’t believe my Oscar will be a sort of magic wand that will wipe away the restrictions on job opportunities for Negro actors.”

For Sidney himself, however, it most certainly was a magic wand. Fast-forward to 1967, and he held triumphant sway over the box office. To Sir, with Love became the eighth-highest-grossing picture of the year – outstanding for a small-budget movie made in the UK.

Leading man Sidney took a pay cut (but smartly negotiated a percentage of the box-office gross, something not done before) to take part in the movie he felt strongly about starring in – a movie that defines his career for many.

Another such role, in Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner, focused on interracial romance – indeed, it was the first Hollywood movie about the topic that didn’t end in a tragedy. And it was a box-office triumph.

“As a black man, he was going to be judged,” said actress Katharine Houghton, who made her film debut as Sidney’s screen fiancée in the film.

“He knew this. He had to be better than a white man. And that was his great gift to America. He chose to be the perfect man.”

Not everyone agreed with that sentiment, though – in fact, backlash was just around the corner as criticism came of his choice of “perfect man” roles in a whiter-than-white Hollywood.

Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner, focused on interracial romance with Poitier starring alongside Katharine Houghton.

(Image: Getty)Said Sidney, “I lived through people turning on me. It was painful for a couple years …”

Painful indeed, as the 1970s approached and he weathered the storm of criticism, with young black Americans questioning how to move forward and show their real stories on screen, as well as questioning why he was comfortable being the only black actor on set.

“It was hurtful. You cannot help but be hurt. It was far from the truth, but I understood the times,” he told Oprah.

“There was a public display of all the rage that [black people] had built up over centuries. If you examine the movies, the criticism I received was principally because I was usually the only Black [person] in the movies. Personally, I thought that was a step!”

He continued, “I was the most successful black actor in the history of the country. I was not in control of the kinds of films I would be offered, but I was totally in control of the kinds of films I would do.

“So I came to the mix with that power – the power to say, ‘No, I will not do that.’ And I did that from the beginning.”

“I lived through people turning on me. It was painful for a couple years…”

(Image: Getty)No matter, Sidney’s time was up – for now. In his 2000 book The Measure of a Man: A Spiritual Autobiography, he wrote, “The angry ‘payback’ of the black exploitation film was just around the corner, and my career as a leading man in Hollywood was nearing its end.”

Instead of his star vehicles, movies like Shaft and Super Fly became black America’s new favourites. Now Sidney took a breath. He knew he was at a crossroads and it was time to take stock.

“I went down to the Bahamas and I went fishing,” he said of his break from the industry. Then, on his return, he began a new chapter in his movie career.

“I decided I wanted to make films, and I entered an agreement with Paul Newman, Steve McQueen and Barbra Streisand,” he said. “We started a film production company called First Artists.”

Poitier established a production company with Paul Newman, Steve McQueen and Barbra Streisand.

(Image: Getty)The team made a number of films including, from 1974 to 1977, Uptown Saturday Night, Let’s Do It Again and A Piece of the Action – all directed by Sidney, co-starring Bill Cosby and considered a trilogy.

Sidney then went on to direct a classic comedy film, Stir Crazy (1980) and another Gene Wilder vehicle, Hanky Panky (1982).

He returned to acting in 1988’s Shoot to Kill, then starred as Nelson Mandela in the 1997 TV drama Mandela and de Klerk, but hasn’t graced our screens since 2001.

Now, at the grand old age of 93, he prefers to spend his time on more relaxing pursuits.

“These days I play a lot of golf,” he told Oprah. “My love of golf far outstrips my gift for it, but I love it. And I read a lot.”

Poitier with Nelson Mandela, whom he portrayed in the 1997 TV drama Mandela and de Klerk.

(Image: Getty)In 2002, Sidney was presented with an honorary Academy Award for his “remarkable accomplishments as an artist and as a human”, receiving a standing ovation from his Hollywood peers and those for whom he opened so many doors.

They included Denzel Washington, who won Best Actor that year for his role in Training Day, and told his hero in his speech, “I’ll always be chasing you, Sidney. I’ll always be following in your footsteps. There’s nothing I would rather do, sir.”

Sidney’s accomplishments also include six children. He has four daughters from his marriage to his first wife, dancer Juanita Hardy, while he and his second wife, Canadian actress Joanna Shimkus-Poitier, have two. It’s a legacy of which he is justifiably proud.

And as for Sidney’s professional legacy? His films are not only classics, they’re undeniably important moments in the history of Hollywood and movie making.