Hilde Hinton spent 20 years trying not to be a writer.

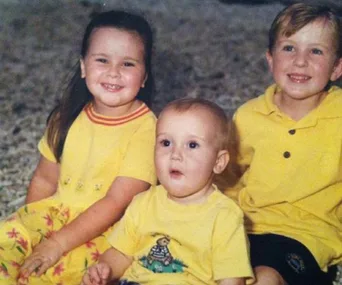

She has always loved crafting words, but as youth gave way to adulthood, she set her writing dreams aside – there were bills to pay, three boys to raise, and two siblings to support, one of whom was wrestling with cancer for a third of her life.

“I chose obligation,” says the 51-year-old.

As Connie and Samuel Johnson rallied the country behind their Love Your Sister campaign, raising $10 million to fight cancer, their big sister was content to remain unseen.

“I’m the Oscar [winner] for the best supporting role,” she says.

“I was there every time they needed me.

“I was a mother figure. That’s what they needed and that’s what I wanted to provide because I felt I didn’t have it.”

Crunch time, though, came a few weeks after Connie’s death in 2017, when Hilde was feeling dazed and deflated, a “gaping hole” in her life.

After badgering her to write for years, Sam gave Hilde a talking-to one night – and it changed everything.

“He actually squared up,” she recalls. “He said, ‘No more hiding behind obligation. The kids are fine – they’re grown up. You’ve got no excuses.'”

So Hilde wrote, in between her shifts as a prison officer, for eight months.

The result is The Loudness of Unsaid Things, a heartbreaking, yet ultimately hopeful book inspired by Hilde’s early years.

It’s about a girl whose mother grapples with mental illness and takes her own life – a lost teenager who can’t articulate her anger and confusion in the fallout.

“She’s a girl who had to grow up too early but really grew up too late – she can’t find her people, a whole lot of unsaid things just develop in every relationship,” says Hilde, who lost her mum when she was 12, Connie was four and Sam three.

As the big sister of Connie and Sam, Hilde struggled to express her grief to them fully.

(Photo: Julian Kingma. Hair and make-up: Julia Green. Styling: Milana De Mina.)“In our family, nothing’s unsaid. [But] no-one spoke about my mum’s suicide. I thought it was bizarre.”

“I didn’t bring it up with Dad; I didn’t bring it up with Connie and Sam because I thought, ‘I’m protecting them – they’re so lucky they’re not going to remember her’, so we never spoke of Mum. In my teenage years I couldn’t find anyone to talk to because no-one wanted to talk about that stuff.”

Today, on a steamy late summer morning, we’re talking about it all on the back porch of Hilde’s ramshackle weatherboard home in Melbourne’s north.

She calls it her house “for the temporarily defeated” and over the years has taken in all manner of strays; there’s a 22 year old currently living in the backyard bungalow.

He’s a friend of one of her three sons: Austen, 21, Sullivan, 22, and Jonno, 30. The younger two still live at home.

Sam won the TV Week Gold Logie Award in 2017, after his portrayal of Molly Meldrum on Molly.

(Image: Getty)Hilde is the first in the family to actually own a house and it’s considered the family’s home base; Sam is also there a lot.

“Hers is a halfway house,” he says. “If there’s not some errant teenagers floating through then there’ll be some rescue dog. Put it this way, I’ve had to turn up bedraggled on many occasions.”

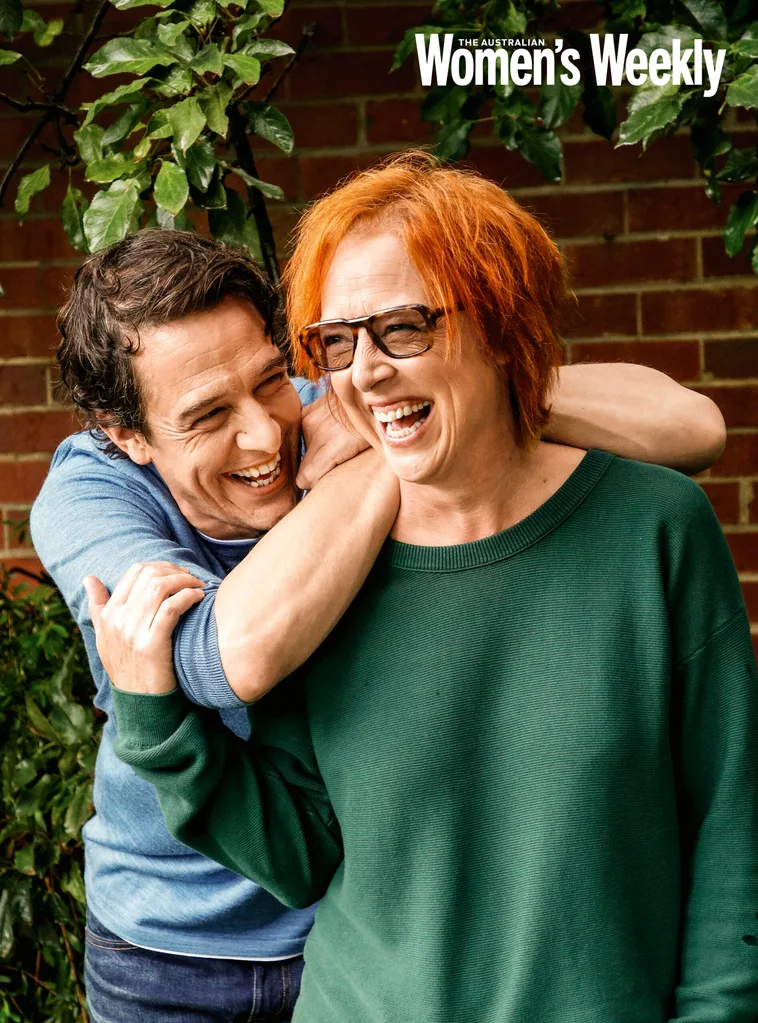

Sporting her shaggy fire-engine red hair and uncanny resemblance to Sam, Hilde greets The Weekly with a hug and we chat surrounded by laundry, next to a ping-pong table and a car bench seat on the ground nearby.

Nailed to the beam above us are dozens of number plates that Sam collected off the road on his 2013 unicycling odyssey around Australia.

The porch has played host to countless family dart and board game competitions, not to mention impromptu parties after Sam won the 2017 Gold Logie and 2018 Victorian Australian of the Year.

It’s also where Hilde announced her long-awaited book deal, prompting Sam and her sons to run around the porch with “windmill arms”, jubilant.

WATCH BELOW: Sam talks to journalist Leigh Sales about Connie and Love Your Sister. Story continues below.

Sam cried when he read the novel – for the pain his sister suffered and for the mother he never knew.

“Hilde’s depiction of my crazy mother was so vivid that it put me there – I met her 40 years after she died,” says the actor-turned-advocate.

“It gave me a true insight into just how much my poor darling sister has been through, and just how much responsibility she had to shoulder. I learnt that my sister belongs on the pedestal I’ve had her on my whole life.”

Despite the age difference, Hilde, Sam and Connie grew up a tight trio in Melbourne. Their parents split not long after Sam was born, and they lived with their dad, Joe.

He was a full-time writer – mostly of novels and histories – but had to supplement his income by renovating houses, so the family moved constantly.

With no TV, the Johnson kids would play imaginary games, ride their bikes and build tents out of bed sheets.

“I was definitely both of their favourites,” says Hilde (named Hildegaard by her Germanophile father).

Hilde and Sam have always been best friends.

“Connie and I had heaps of issues,” says Sam, “but with Hilde we had none. Hilde taught me I could do anything and be anything. I always joke that if she got cancer I’d ride around the country twice for her.”

Their mother, Merrill, a poet, was volatile and mentally unwell, but their dad insisted that Hilde visit her.

One day, when she was 12, she lingered at the park and milk bar before forcing herself up the scary stairwell of the housing commission flats. She was late – and found her mother dead.

Hilde blamed herself for not being there early enough to save her. Apparently she has never been late since.

At 15, Hilde left home and moved to Sydney, living in a series of share houses while finishing high school. Afterwards, she worked in an air filter factory and fell in love, giving birth to Jonno when she was 20.

Hilde’s memories of her “character-building” childhood are still vivid, and form the basis of her book.

“I want people to think about children having mentally ill parents,” says Hilde.

“Suicide is happening every day and it takes the whole family with it. I’d like people to think about what their young are going through.”

Writing the novel unearthed a lot of repressed issues, she says, but it also exorcised them.

“I hated my mother until I wrote it,” she says, before correcting herself. “Oh, hate’s a strong word.”

“I was angry. I resented not having a mother. But my feelings towards her have changed completely. I’ve forgiven her. It wasn’t her fault.”

If the book sounds depressing, it’s not. It’s sad, but also wry and irreverent.

Fellow Australian author Favel Parrett calls it “a wise, funny, brave novel and a story that you will never want to forget”.

Sam and Hilde share an uncanny resemblance.

(Photo: Julian Kingma. Hair and make-up: Julia Green. Styling: Milana De Mina.)Hilde has always been an avid reader.

In fact, encircling her right arm is a new tattoo – six stacks of books, featuring the authors and titles that have made an impact on her, including Milan Kundera and Christos Tsiolkas, Bridge of Clay and People of the Book.

Hilde opened several second-hand bookshops with her father in the ’90s, after 12-year-old Connie was diagnosed with the first of her three bouts of cancer, and Hilde returned to Melbourne with baby Jonno.

When Connie’s relationship with her father broke down at 15, she moved in with Hilde.

In turn, Connie was unflaggingly supportive of her big sister – the only one who didn’t tease Hilde for not finishing anything, whether that be the law degree or the locksmithing course.

When Hilde told Connie she wanted to be a prison officer, they did the whole application on the phone together.

“Connie just gave you that boost to have the courage to try something,” says Hilde, “and that’s going to be greatly missed in this family.”

WATCH BELOW: We remember Connie Johnson and her brave fight. Story concludes below.

Throughout the family’s ups and downs, including Joe’s death a decade ago, Hilde has buoyed them all.

“She’s our hero,” says Sam, who lost a girlfriend to suicide in 2006 and later struggled with depression.

“She taught me that despite the suffering there’s still an abundance of joy to be found, and without that from my sister, the darkness would have swallowed me.”

Sam paints Hilde as the madcap life of the party, a source of endless enthusiasm and sometimes unwelcome honesty, but also a mother hen.

Last year, he convinced her to join him on the Queensland and NSW legs of the latest Love Your Sister tour, and she plans to set off again in May, to South Australia.

The experience – meeting people touched by cancer in country towns, at bingo nights and family fun days – has been life-changing.

“I think about Connie all the time out on the road,” says Hilde. “You feel like [her death] wasn’t for nothing.”

Hilde reaches for a rollie cigarette and fans herself in the heat, blaming menopause. She picks up her book and smells the pages with a palpable sense of satisfaction.

“It’s unbelievable,” she says. “It’s never too late. If you want something you’re the only thing stopping you.”

Usually, she says, “50-year-old women don’t write books because they think they can’t”, but Sam’s affirmations eventually sank in.

“Encouraging my sister to tell stories over the 20 years that it took to make happen is the single most significant thing I’ve ever done,” says Sam.

“I always knew she’d be the famous one – and here she comes.”

The Loudness of Unsaid Things, published by Hachette Australia, is out March 31.

The April issue of The Australian Women’s Weekly is on sale from Thursday March 26.

The April issue of The Australian Women’s Weekly, on sale now.

(Image: AWW)