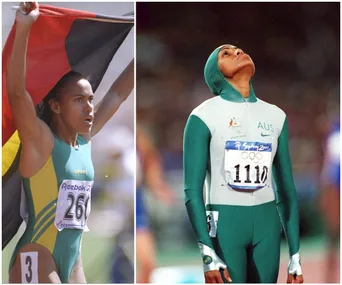

It was Day 3 of the Tokyo Olympic Games when it suddenly occurred to many Australians that a new “Age of the Golden Girls” might be dawning.

Hot on the heels of a world-record-breaking 4x100m freestyle win by Emma McKeon, Cate Campbell, Bronte Campbell and Meg Harris, Ariarne Titmus produced one of the great moments in Australian Olympic history, beating US legend Katie Ledecky in the 400m freestyle final.

From there poured a deluge of gold.

As had happened in Melbourne in 1956, Australia’s mounting medal tally was being powered largely by the sisterhood.

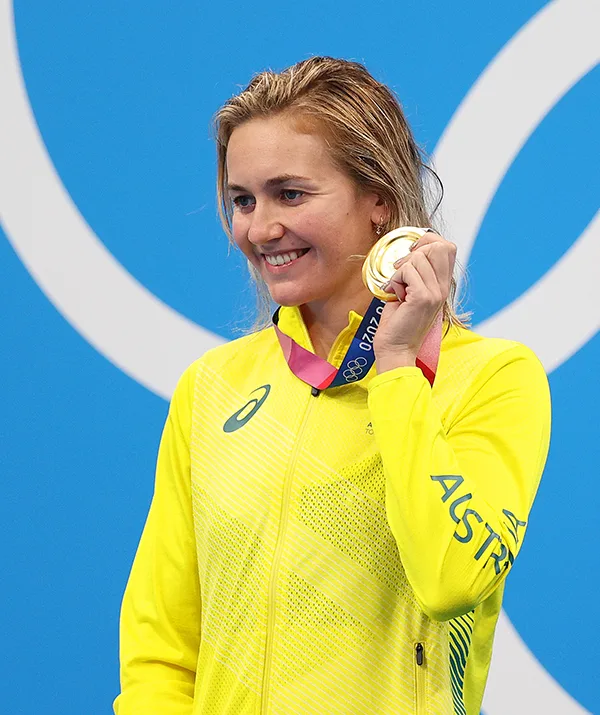

Ariarne Titmus in the moments after her 400m freestyle victory.

(Getty)Back then, it had been Golden Girls Betty Cuthbert, Dawn Fraser and Shirley Strickland.

This time around, it was Emma, Ariarne and Kaylee McKeown.

Dawn Fraser’s famous 1956 comment that “Australian women have always been gutsier than the men” was ringing true again, and the swimming legend was happy to stand by it.

“[The Dolphins] were absolutely fantastic,” she enthused to The Weekly. “They outshone the men again.”

While most of the glory surrounded Emma, Ariarne and Kaylee, there was plenty of guts (and grace) displayed by the whole team, young and older.

Dazzling performances in the pool were followed by stirring moments of friendship that met the Olympic ideal.

Gold-standard mentoring paved the way for golden swims.

“It wasn’t just the way they performed, it was the way the teammates spoke to one another, the way they applauded each other, the way they all got on,” says Dawn.

After Emma secured gold in the 100m freestyle in an Olympic record time of 51.96 seconds, bronze medallist Cate Campbell enveloped her in a hug across the lane ropes, saying, “I am so proud of you” before raising Emma’s hand in victory.

And who could ever forget the sight of Kaylee McKeown, who had just won gold in the 200m backstroke, inviting bronze medallist Emily Seebohm to share her spot on the top podium during the medal ceremony?

Kaylee McKeown brought bronze medallist Emily Seebohm up onto the top podium during the medal ceremony.

(Getty)“Em’s been around for so long. She deserved to be on that gold medal podium just as much as I did,” Kaylee explained afterwards.

Emily, a four-time Olympian, was quick to match Kaylee in the humility stakes.

“Kaylee, you are truly the most amazing, humble, beautiful person and giving you your medal and sharing the podium with you goes down in history as one of my favourite moments in swimming!” she wrote on Instagram.

Former Commonwealth Games swimmer Joh Griggs, who is now a commentator for Channel Seven, says the Australian team’s obvious respect for each other has captured the public’s imagination almost as much as their sizzling swimming.

“They’re totally about the team,” she tells The Weekly.

“Yes, their individual efforts are important, but the team is more important. And that’s an impressive place to reach.

“The respect they were showing to each other was absolutely beautiful to see; the moments like Kaylee and Emily giving each other the medals. In times past, swimmers would have been pitted against each other to such a degree that it wouldn’t have happened.”

Swimming legend and Olympic gold medallist Leisel Jones agrees.

“It’s sort of starting to look like the team I remember from around 2000-2004, where we were super-successful, but there was so much support going on in the team,” she says.

“And that’s why they’re so successful – because that culture is so good.”

Ariarne Titmus’ mother, Robyn, says the Dolphins’ unity gave her and husband Steve comfort that their daughter would be well cared for as she headed to a foreign country, in the midst of a global pandemic, with the weight of Australia’s expectations on her young shoulders.

“The Australian team – the culture that’s been created – is at an all-time high,” Robyn tells The Weekly.

“Their individual efforts are important, but the team is more important,” says Joh Griggs.

(Getty)“They are like brothers and sisters, or cousins. They understand the emotional roller-coaster.

“Ariarne cried watching Emma and Cate in the 100m final, and that’s really special. If your children have those values and qualities, that’s everything you could ever ask for.”

The team cohesion is no accident. In recent years, the Dolphins have doubled down on their relay focus in a bid to build both unity and depth.

The swimmers have been gathering at least once a year to train together for a week.

“We’ve always been close because we grew up racing each other and going on camps together,” Emma says, speaking to The Weekly from quarantine at Howard Springs the morning after her triumphant return from the Games.

“We push each other and we challenge each other, but we do that in a really supportive way,” adds Cate Campbell.

“There’s no malice and no animosity towards one another.”

More than that, senior swimmers like Cate, sister Bronte and Emily Seebohm strive to nurture their younger teammates.

“These are the people who just constantly check in on them, check they’re okay, check how they’re handling the pressure,” explains Joh Griggs.

“That’s the stuff you don’t see on camera. We had two 17-year-olds on that team. For them to have the experience of people who have gone to three or four Games and are willing to share that, that’s powerful stuff.”

The Dolphins’ focus on relays and teamwork paid off in spades in Tokyo.

Not only did Australia collect medals in six of the seven swimming relays, eclipsing the 1956 gold harvest, but it helped to deepen the esprit de corps.

Kaylee, Emma, Cate and Chelsea Hodges embrace after an incredible relay win.

(Getty)“Being in a team is so much better,” Kaylee said after she, Emma, Cate and Chelsea Hodges pulled off a stunning come-from-behind win in the 4x100m medley relay.

“There is so much more hype around it, and I’m with girls who are so decorated in the sport.”

Emma McKeon’s father Ron, himself a former Olympic swimmer, tells The Weekly there is a marked selflessness among the current crop of swimmers.

“When they get behind the blocks, that selflessness narrows to self, but once that hand hits the wall, it changes straight back again,” he says.

This focus on team helped, Ron believes, to lift individual performances – and none more so than those of his unassuming daughter.

Emma wrote herself into the history books in Tokyo, overtaking Ian Thorpe and Leisel Jones to become the greatest medal winner in Australian Olympic history and the first Australian ever to win four golds at a single Games.

She also became the first Australian, male or female, to win the splash-and-dash 50m freestyle and only the sixth person ever to complete the 50-100m freestyle double.

Her career total of 11 medals makes her the greatest non-American swimmer of all time.

Despite her triumphs, Emma tells The Weekly her most memorable Tokyo moment was FaceTiming her family after her 100m freestyle win.

“To watch them celebrating probably harder than me was really nice to see, because they’ve been along on the whole journey with me,” she says.

Emma’s mother Susie, a former Commonwealth Games swimmer, found her daughter’s assault on the record books head-spinning.

“It’s still surreal that she’s now mentioned in the same breath as Shane Gould, Dawn Fraser and Ian Thorpe,” Susie laughs.

Emma McKeon with her parents, Susie and Ron.

(Supplied)“When I was young, my hero was Shane Gould . Emma’s heroes were Susie O’Neill and Jodie Henry. To think that for kids today their hero will be Emma, that’s still surreal.”

It is a sign of the extraordinary depth of the Dolphins’ talent that Emma’s remarkable swim meet could arguably have been overshadowed.

Asked to pick the most exciting moment from the Tokyo Aquatics Centre, Joh Griggs hesitates only briefly before nominating Ariarne’s victory in the 400m freestyle.

“She was just so cool and so composed and so mature, and handled everything so brilliantly against the greatest of all time in Katie Ledecky,” she says.

“I had so much admiration for this young girl being so together and articulate after all that pressure that was piled on her by all of us.”

The Dolphins’ ability to stay focused and grounded at the Olympics – an environment that former head coach Jacco Verhaeren likened to a “circus of unexpected circumstance and unusual pressure” – impressed commentators, especially after years of failing to produce their best at the Games.

Joh has commended Ariarne Titmus on her incredible composure during the games.

(Getty)There was no swagger from the pool deck (apart from, of course, Ariarne’s hilariously flamboyant coach Dean Boxall), only quiet smiles and hugs.

“They seemed to be the most well-rounded as far as not piling so much pressure on themselves that they’re forgetting to enjoy themselves,” says Joh.

“They looked like they were having fun and looked like they love to race.”

She notes that today’s swimmers seem to have a more balanced life outside of swimming than she did, with many studying at university.

“That is so different from the era that I swam in,” Joh says, adding that she is “really excited” to see this positive message going out to young swimmers.

As if to prove the point, the day after her final swim in Tokyo, Emma received her Bachelor of Public Health and Health Promotion from Griffith University.

Emma received her Bachelor of Public Health and Health Promotion the day after her final Olympic swim.

(Getty)“It’s important not to just swim and to have something else you’re passionate about and working towards,” says Emma.

“I think that’s definitely helped my mental side.”

With their professionalism, talent, humility and grace, the new Golden Girls of the pool have given millions of Australians a boost during COVID-19 – as well as inspiring the next generation of swimmers.

“It’s so lovely to walk out into the street and have young kids say, ‘I hope I can be as good as Ariarne and Emma. I am going to try to get to the 2032 Olympics!'” says Dawn Fraser.

“I remember being young and being inspired by so many great athletes,” adds Emma.

“So to think I am doing the same thing is quite overwhelming.”

Leisel Jones concludes that when she looks back on the week, “I feel like it’s given everyone hope and entertainment. It’s been such a positive influence on all of our lives across Australia.”

Read more in the September Issue of The Australian Women’s Weekly on sale now.

.jpg?resize=380%2C285)