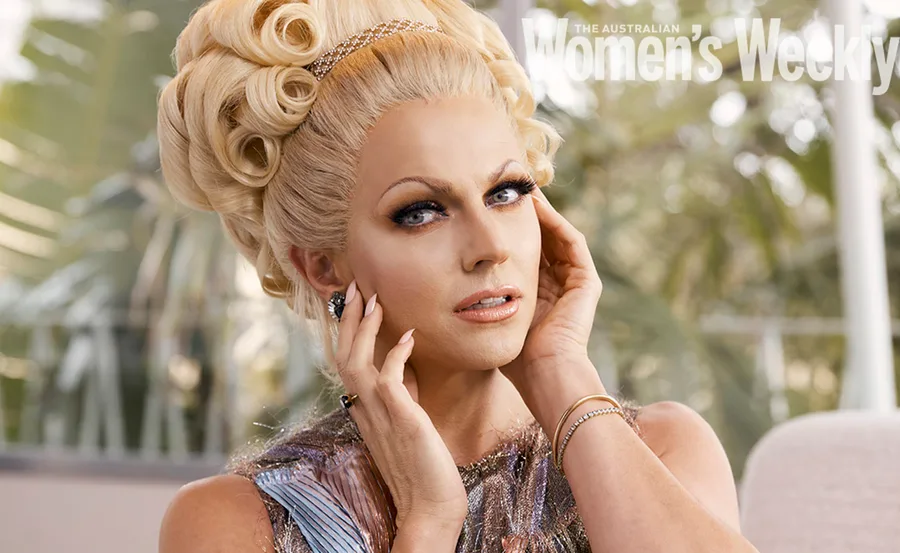

It takes three hours or thereabouts at The Weekly’s photo shoot for Shane Jenek to emerge as Courtney Act, with the donning of one of a variety of blonde wigs lined up on his dressing table a glorious crowning moment.

The wigs carry glamorous echoes of iconic bombshells, be it Farrah Fawcett, Marilyn Monroe or ABBA’s Agnetha, and while you can still see Shane – the chiselled cheekbones, lithe toned body and piercing blue eyes of the boy from Brighton, Brisbane, are all in beautiful evidence – Courtney really is a whole new woman. Or is she?

Shane is Courtney and Courtney is Shane – they are one whole multifaceted, complex human being.

(Image: Peter Brew-Bevan/Are Media)“That’s the interesting thing, I don’t feel different,” Shane tells me the following day, kicking back in his non-drag ‘relaxing at home’ baggy pink pants with white and pink floral short-sleeved shirt. As Shane, this 39-year-old global celebrity is movie-star handsome, impeccably polite, quietly charming; his voice slightly deeper and mannerisms less pronounced.

And as I settle in for a starkly personal and often heart-wrenching discussion, the searching, smart intellect behind Courtney Act the performer comes into sharp focus. I soon realise that to see Courtney as some sort of alter ego, the sassy ‘she’ Shane perhaps longed to be growing up in suburban Queensland, is to miss the point entirely. Shane is Courtney and Courtney is Shane – they are one whole multifaceted, complex human being.

“What I do feel is more entitled as Courtney to act in certain ways, because people look at me differently. That is femininity, that is costume, that is being different in the world,” Shane explains.

“I was the only person in the room at the photo shoot yesterday – that I know of – who was assigned male at birth and was dressed femininely or ‘as a woman’. A police officer puts on a uniform and goes to work, and there’s a certain entitlement that comes with that uniform, but for me Courtney was the bridge that allowed me to express my femininity in a world where that wasn’t allowed, certainly at the time.”

Today Courtney Act is a star, not just of the gay community’s drag clubs, but of mainstream reality TV – Australian Idol, Dancing with the Stars, Celebrity Big Brother UK – and most recently the host of ABC’s interview show One Plus One and a commentator on the political soapbox that is Q+A. But the road to finding her has not been easy.

Shane traces that path in his courageous memoir, Caught in the Act. It’s a powerful, funny, revelatory read that gives full, unexpurgated details of his journey, delving into every corner of a technicolor world with brazen honesty. The life story that unfolds also examines the complexities of sexual identity in forensic detail, and the damage wrought on young developing minds by society’s notions of “normality”.

Beyond the spiteful schoolyard teasing that is sadly the experience of so many LGBTQIA+ children, Shane goes to the heart of how he feels society muffles and confuses personal development, and the far-reaching consequences on our children’s mental and physical health. In his case it pushed him to the verge of suicide, as he put his head underwater in his bath at the age of 11 and contemplated what it would feel like to stop living.

“These long hours, days, months I have spent going back and immersing myself in childhood memories have often been painful,” he writes. “I’ve cried, sobbed and released so much pent-up emotion I never knew existed. I would often find myself rocking back and forth with tears streaming down my face, my arms wrapped around myself. My present self would say to my younger self, ‘I’m sorry I wasn’t there to protect you’.”

In his parents Gilberto and Annette, Shane hit the jackpot. Both in their own ways were non-conformist and celebrated difference, and they adored their funny, flamboyant, sunny son. They each had a daughter from previous marriages before Shane was born, and although his half-sister Kim was raised in the family home until Shane was about eight, he says, “I did feel like an only child. We were our own special unit.”

Shane goes to the heart of how he feels society muffles and confuses personal development.

(Image: Peter Brew-Bevan/Are Media)Gill is “a wonderful man” who proudly sported a thick bushy moustache and “unlike other dads was free, fun” and outwardly affectionate to Shane. When he was injured in a terrible car accident and was all but “read the last rites” by doctors, Gill’s stepfather sent him to a naturopath to fix his injuries. The experience proved so life-changing that he set about getting qualified in naturopathy and Chinese medicine himself.

“Mum and Dad opened Brighton Natural Therapies clinic in 1987,” notes Shane. “I didn’t realise this at the time, but not only was he a naturopath and acupuncturist in Brisbane in the ’80s, which was already off-centre, but his moustache was his form of drag. He had an ad on the front page of the Bayside Star for the clinic and there was a picture of Gill with the moustache. It’s only looking back that I realise that being a naturopath and having a moustache like that is something different. I didn’t think it was weird, I just intuitively saw him being himself; all I got was the strength of his confidence.”

Annette was equally inspirational and would leave love notes in Shane’s lunch box. “Mum made sure I knew I was cherished,” he says. She wore a white “power” suit to work in the clinic and Shane saw her as his “superhero”. “Mum wasn’t ostentatiously glamorous at all, but I now recognise that she was glamorous in her own way. She was a nail technician and beauty therapist when I was very young and she would always have tastefully long maroon acrylic nails, and I always remember her at dinner, pulling out her lipliner and touching up her lipstick. Beyond those superficial things, what I remember most is a sense of warmth and love and support from both my parents.”

When Shane was in trouble at school and facing the cane, the headmaster called in his mother to ask her approval. “I don’t remember what they said I’d done wrong, but I definitely didn’t do it. Mum turned to me and she asked me what happened. I said, ‘No, Mum, it was like this.’ She said, ‘Okay,’ and told the principal, ‘No, my son didn’t do that, and no, you can’t give him the cane.’

“I sobbed when I recalled that story. It was such a fundamental time with bullying at school, and to know that what I told my mother would be believed in the face of the principal, who was one of the most important authority figures there was in my life, was such an impactful lesson to learn at such a young age – that my mother would believe what I said over an authority figure.”

At school there was one particular group of boys who picked on Shane mercilessly. Back then he had no clue he was attracted to boys, nor where his sexuality was at, but nevertheless he was called “faggot” and “poofter”. “I was bullied for what I can see now was my air of femininity,” he says. “I knew these words were slurs and not anything I wanted to be. I wasn’t aggressive. Or tall, or strong. I wasn’t good at sports. I wasn’t toeing the party line, and all the boys let me know so. They’d try to shame me into being a man. I definitely felt shamed, but I never felt like a man,” he explains.

“They’d try to shame me into being a man. I definitely felt shamed, but I never felt like a man.”

(Image: Peter Brew-Bevan/Are Media)This idea of not being “a real man” haunted Shane, creating dark feelings that swirled around his head. Even though Shane’s parents never once questioned how he looked, behaved or dressed, he ached to find someone like him reflected in the world outside his childhood front door, a sign that would validate how he felt inside.

“On television if there was ever an example of a queer person, it was Carlotta and Bob Downe, and that was once a year on Good Morning Australia. There was no example of fluid or a non-binarised identity,” he explains. “I guess in the ’70s and ’80s there was David Bowie and Boy George, but in my world of awareness those people were outliers. There wasn’t anything usual about those people. They would always stand out.

“It’s fascinating, because when you don’t have those examples presented to you, you really are lost. And when Mum and Dad read the book, they said, ‘I wish you’d told us, we didn’t know,’ and I said, ‘I didn’t know!’ It wasn’t possible for any of us to know because we didn’t have that perception.

“When you don’t see yourself reflected back in the world, it causes you to ask questions about your own identity, because we are tribal and we do look for social confirmation in the world around us. As kids, especially in school, you look at other people’s behaviours to try to understand your own and confirm whether something’s right or something’s wrong. When you don’t see yourself reflected back you internalise that, and that becomes shame.”

Shane’s saviour was discovering performance. The Fame Talent Agency and Theatre Company ran weekly singing, dancing and drama classes in the Brisbane area, and Shane’s local group met at the Strathpine Community Centre. There he met the Origliassos – Julian and his two sisters Lisa and Jessica, later the pop duo The Veronicas. The family became a huge part of Shane’s childhood and they are all still friends today.

“Colleen – Lisa, Jessica and Julian’s mum – recently passed away and I’ve dedicated the book to her because she was such a wonderful lady. Lisa and Jessica and Julian, and their dad Joseph, were very positive when it came to performance. I think we all had dreams of stardom and they really supported that. My parents did as well, but they weren’t nearly as hands on.”

Shane had found his tribe and also, as it turned out, his future career. “I remember being celebrated there,” he notes. “I think I have a natural talent for performance and for coordination and movement, so it probably helped that I was positively reinforced there, but I think also I excelled at it because I loved it so much.” The Fame Agency was also a refuge from having to try to conform. “I was never told, nor did I ever feel I had to ‘butch it up’,” he writes.

School continued to be traumatic for Shane and despite being a bright student, his work suffered. His plans to go to university and also to NIDA – the National institute of Dramatic Art in Sydney – foundered, and by the age of 17 Shane says he felt as if he’d ruined his life. But everything was about to change. In 2000, aged 18, Shane arrived in Sydney, supposedly to attend an open day at NIDA and research his chances of a future in acting. He headed straight for Taylor Square on Oxford Street, the gay heart of the city, and all at once a whole new world opened up. “I found my real home,” he says.

Here Shane discovered his sexuality properly for the first time. His encounters were passionate and furious and filled with a lustful joy. He describes them in graphic detail in the book, and even though he is aware many will be shocked by the promiscuity of that time, he knew he had to be honest and open, to tell the truth for the first time.

Shane had found his tribe and also, as it turned out, his future career.

(Image: Peter Brew-Bevan/Are Media)“That’s the point, it’s about sharing,” he says. “I know it’s intimate and I know it’s personal, but those sorts of stories are very common in heteronormative culture, whether it be in books or in films or on TV – you hear lots of stories of sex. But it’s very uncommon for people to hear about gay sex, and it probably will be the first time a lot of straight people will be reading about those sorts of stories. I hope that with the foundation of my childhood and of the journey I have been on, people will read it and understand my experience and have empathy. I think that’s the whole point of storytelling, that you get to walk a mile in someone else’s shoes.”

What Shane found for the first time in his adult life was that “I was worthy as a human, because when someone else is attracted to you, it validates your existence,” he says. With a new sense of self and excited to learn more, Shane moved to Sydney full-time and developed a fascination with the city’s drag scene. The transition to trying drag himself and the birth of Courtney was a no-brainer.

Next he had to come out to his parents. He was super-nervous but needn’t have been; true to form, they totally accepted that their son was gay. Their love was unconditional.

Shane’s performance talent, coupled with the visual impact of Courtney, kick-started his career. Soon he was putting on his own drag shows on Oxford Street and developing the persona of Courtney Act. When in 2003, he auditioned for Australian Idol and was turned down as Shane, he famously returned the following day as Courtney and got through. It was not only a landmark day for Courtney, but the first time an LGBTQIA+ contestant had openly appeared on Australian reality TV.

The rest, as they say, is history and though Courtney’s career has had ups and downs – Shane felt very burned by the divisive editing of RuPaul’s Drag Race, in which Courtney was painted in a mean, bitchy light – winning UK’s Celebrity Big Brother was a triumph that showed viewers the sharp intellect beneath the blonde wig, as the drag icon was pitched in a final showdown against conservative politician Ann Widdecombe. “People treated me with a new level of respect that I wasn’t familiar with before Big Brother or in Australia and the US,” notes Shane.

“When I came back from Celebrity Big Brother, I got asked to be on shows like The Project, which I never had before, which was wonderful, and then I got asked to be on The Drum, Q+A and One Plus One.”

Courtney Act is about to return to Dancing With The Stars for an All Stars season.

(Instagram)Another pivotal moment was Shane’s story being documented on ABC’s time-honoured Australian Story last year. “[The fact] that my story got told on Australian television and watched by the sort of people who watch the ABC was really important for me,” he says.

In 2022 Courtney joins the Sydney Theatre Company to star as Elvira in Noël Coward’s classic play Blithe Spirit. “It’s a leading lady role. There’s no gender bending, I’m just playing a woman in a straight play,” says Shane, smiling.

If you or someone you know has been affected by any of the issues raised in this article, help is always available. Call Lifeline on 13 11 14.

Read this story and more in the December issue of The Australian Women’s Weekly – on sale now.