Anthony Albanese was just a couple of blocks from home. It was a cool, cloudy January afternoon, the first working week of 2021, and he’d put in a solid day at his electorate office in Sydney’s inner west.

Anthony and his humble but hardy Toyota turned west into a Marrickville side street. Neighbours were out walking their dogs, cicadas were buzzing, kids were chatting and laughing as they tumbled off the 423 bus.

Then suddenly, everything stopped. Out of nowhere, a 17-year-old driver in a Range Rover veered onto the wrong side of the road and rammed Anthony’s car with force. The leader of the Federal Opposition was trapped in his vehicle, in shock and in pain from external and internal injuries.

It was a life-threatening smash.

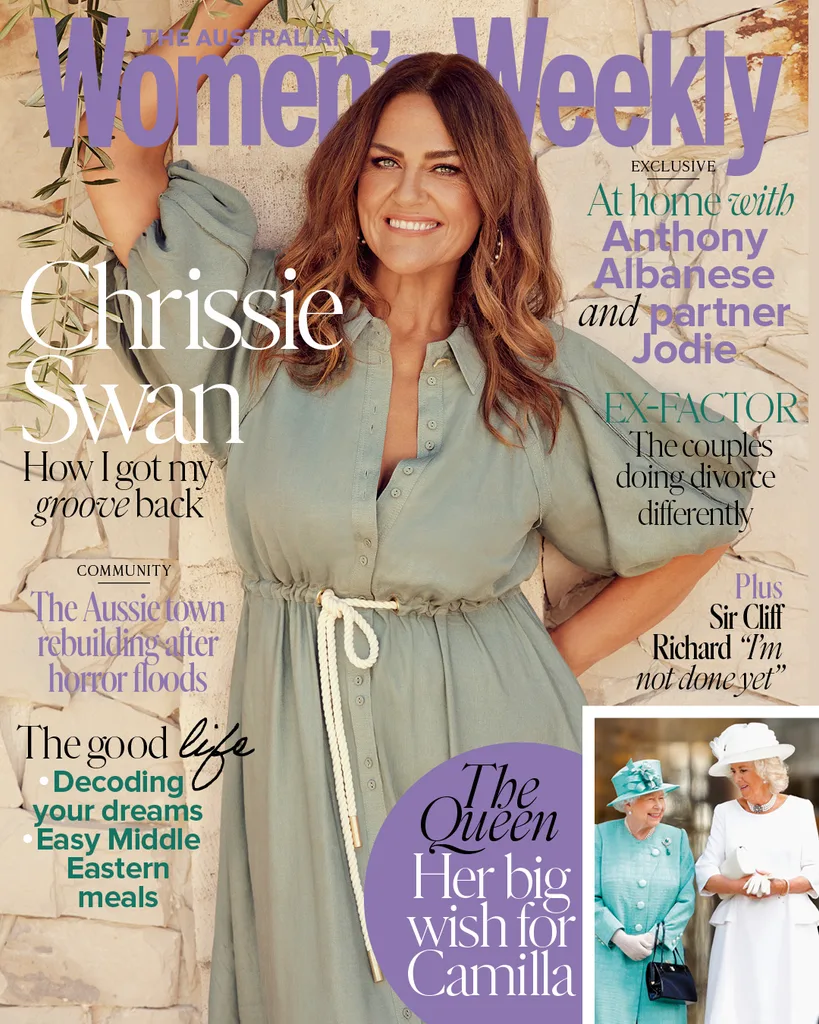

Anthony and his partner Jodie.

(Photo: Alana Landsberry)“If this accident was 10 years ago, I wouldn’t be speaking to you here,” he’d later tell the media.

Someone called an ambulance. Someone else phoned Anthony’s office. His partner, Jodie Haydon, and his then-20-year-old son Nathan were alerted too.

Coming so close to death, Anthony says, gave him the impetus to reassess his life. It encouraged him to value his health and fitness a little more, as well as the challenges and opportunities that stood before him as leader of the party that has been his calling since he was a kid.

The accident gave Jodie’s life a jolt too.

“I got the phone call,” she recalls, “and drove immediately to the scene. I saw the mess of a car before I saw him and thought, ‘He couldn’t survive this.’ It was very scary, and in that moment, you realise just how much you love this person – the fear of losing them. As I jumped in the ambulance and saw Anthony, I knew then the depth of my feelings towards him.”

The couple had met a year earlier, at an event in Melbourne where Anthony had been speaking.

He’d asked whether there were any South Sydney rugby league supporters in the audience. “Jodie yelled out, ‘Up the Rabbitohs’,” he recalls with a wide grin.

Later, he introduced himself and learned that they not only had a football team in common, but that Jodie lived in his electorate. “We had what I thought would just be a drink at Young Henrys in Newtown, and we got on really well. That’s how it started,” he says.

Neither was looking for a relationship. “I’d reached a point in my life where I was enjoying being single,” explains Jodie.

Anthony was still emotionally bruised by the sudden departure a year earlier of his partner of 30 years (wife for 19), former NSW Deputy Premier Carmel Tebbutt. It was as amicable as it could be and no third parties were involved, but for Anthony it was heartbreaking.

Nathan went on to spend time with both his parents, but has largely been based with his dad.

“In that moment, you realise just how much you love this person” Jodie on arriving at the scene of Anthony’s accident.

(Photo: Alana Landsberry)Then, out of nowhere, came Jodie, and the ease and joy that sprung up between them that night at a backstreet brewery in Newtown told Anthony that this was a life-changing connection.

When The Weekly arrives at his Federation bungalow in the sleepy, suburban end of Marrickville, Anthony (Albo to his mates, his constituents, just about everyone) is unpacking the dishwasher. Jodie, who lives a couple of suburbs away in Stanmore, is pouring tumblers of iced water for our crew.

This is their first formal interview and photo shoot together, but it’s plain that these two are relaxed in each other’s company, whatever the situation.

Perhaps in part that’s because they have such a lot in common. Jodie and Anthony both wear their hearts on their sleeve, and they were both formed by quintessentially Australian, though very different, childhoods.

Jodie, now 43, grew up on the beaches, BMX tracks and netball courts of the NSW Central Coast, the daughter of public-school teachers.

Her grandparents (both teachers as well) lived nearby, and Jodie’s greatest inspiration was and is her grandmother, who is 93.

“She had nine children and was a schoolteacher. Today that would seem almost insurmountable – nine kids and a career,” Jodie says with pride.

“She is simply remarkable. Her cheeky sense of humour and ‘just get on with it’ attitude have been a driving force for me. Her life wasn’t easy, growing up in the country with no electricity as a child, living off the land, going through times of trauma and hardship, then putting herself through teachers’ college. It shows true grit and determination. She is the glue that holds our large extended family together, and I love her dearly.”

Anthony was raised by a single mother in council housing in Camperdown, not far from where he lives today.

His mother, Maryanne Ellery, worked as an usherette and saved like crazy for her fare to London on the Sitmar ship Fairsky. Her brother, George, who was a comedian and had a gig on the ship, acted as a very half-hearted chaperone.

The most important thing Anthony’s mother gave him was unconditional love.

(Photo: Alana Landsberry)On board, 25-year-old Maryanne met a handsome Italian steward, Carlo Albanese, and their relationship continued after the ship docked in England. Months later, when she found she was pregnant, Carlo broke the news that he was already engaged to marry a girl from his village, and then left.

Maryanne was advised to adopt out the baby and carry on with her life. A story was concocted that she had in fact married Carlo, and his sudden death in a car accident had caused her to lose the child. But she couldn’t carry it through. Maryanne returned to Australia – she did claim to be a widow and adopted the name Albanese – but Anthony was born on March 2, 1963, and his happiness and wellbeing became the cornerstones of her life.

“It was really courageous of her,” Anthony tells The Weekly, sitting on his back porch beneath a trellis of grapevines. Across the lawn is a Hills Hoist and a garden bed overflowing with rosemary and mint.

“It was expected that I would be given up for adoption, but she didn’t want to do that, and she was strong enough to resist it. Mum had very strong values … She would have seen herself as a feminist, though she might not have used that language. She was very strong and very determined to not take nonsense from anyone.”

Anthony with his mother, Maryanne.

(Image: Instagram)The most important thing she gave her son, he says, “was unconditional love, which gave me confidence”. She also seeded his interest in politics.

“Mum was a rank-and-file member of the Labor Party. She used to listen to talkback radio. She had an awareness about her place in the world. She raised me with three great faiths: the Catholic Church, the Labor Party and South Sydney District Rugby League football club.”

When he was roughly six, Maryanne decided her son needed a father, so she married. It lasted less than three months and it wasn’t an experiment she repeated.

“He was pretty awful to her,” Anthony explains. “It was a violent relationship … He was abusive towards her. He wasn’t physically abusive towards me, but he was [emotionally] abusive. She ended the relationship and he continued to behave badly … The nuns would keep me after school because he had threatened to take me. It was terrible, but my mum was really strong.”

WATCH: Brisbane tragedy puts Australia’s domestic abuse crisis in the spotlight. Story continues after video.

Growing up with Maryanne, respecting both her strength and vulnerability – she suffered from crippling rheumatoid arthritis and often needed Anthony’s help as much as he needed hers – influenced his relationships with women and also his politics.

“He saw how resilient and resourceful his mother was during the hardest of times,” says Jodie. “She taught him respect and also nurturing. That has undoubtedly shaped him, and Anthony has well and truly advocated for women.”

As Linda Burney, a friend of 35 years and the Federal Member for the seat of Barton, puts it: “He understands social justice because he’s lived it. His life experiences really inform the person he is and the way he works with people.”

Both Linda and Jodie believe Anthony has a gut-level belief in such old-fashioned values as equality, loyalty and mateship. He also has an optimism about Australia that springs from his Camperdown childhood.

“There was a sense of community there,” he explains. “You felt like you belonged. On one block, there was the 10-storey Johanna O’Dea Court and then the Alexandra Dwellings, two-storey duplexes, where I grew up.”

“She taught him respect and also nurturing. That has undoubtedly shaped him.” Jodie speaking about how Anthony was raised.

(Photo: Alana Landsberry)There was the Children’s Hospital opposite, a Weston’s Biscuit Factory to one side and a foundry to the other.

“Everyone knew each other. We had a phone and a little moneybox, and people would knock on the door and come in to make a call,” says Anthony. “No one moved out. My entire childhood, my neighbours were the Hukins, the Campbells, the McGraths, the Thomas family, the Pinchams at the back, the Andersons, the Cotters.”

The See girls, Christine and Lorraine, were also neighbours. Thanks to them, Anthony heard an early Led Zeppelin album, which seeded a lifelong love of rock music. Tracey and Shelley Hukins (who took him to see AC/DC) and his cousin Karen Jane (who introduced him to classics like Van Morrison and The Beatles) also get a nod.

When he was 15, he took a job at Grace Bros. and saved for a record player. The first album he bought was Elton John’s Honky Château.

He’s still a regular at music festivals, DJs charity events and votes in the triple j Hottest 100 every year. Music runs in his veins with the scent of that industrial, biscuity Camperdown air.

Anthony in his youth, from a photo he shared on Instagram.

(Image: Instagram)“Anyway,” Anthony says, “that’s the kind of community it was. My mother was born and died there. For 65 years she lived in the same house.” And to bring home that message, he tells the story of the day, in 2002, when Maryanne died.

“She had an aneurysm on Mother’s Day,” Anthony says quietly. “I was coming back from a conference in Canberra to take her and my auntie to lunch when she was found. She struggled through for a fortnight in intensive care … Then I got the final call to go up to the hospital because she was dying. And when I came out that last time, it was just after six o’clock in the morning, and my neighbours Scott and Sherie [Dewstow] were there, waiting. Somehow word had got out and there they were. That sense of community is a big deal. It’s really important to me.”

By the time Maryanne died, Anthony had battled his way out of Camperdown. He’d been the first in his family to finish school and had gone on to study Economics at the University of Sydney. He’d been elected to his local seat of Grayndler, married Carmel and become a dad.

It was shortly after Maryanne died that he began to wonder about his own father. As a kid, Anthony, like everyone else, believed that Carlo had died in a car accident. Then, when he turned 14, his mother sat him down and told him the truth.

“It’s funny,” he says, “when Mum told me, I was very much, ‘Well, he chose not to be part of my life. I don’t need anything from him.’ Mum said, ‘He might still be alive, if you’re interested in trying to find him.’ And I was immediately like: ‘No, I’m not.’ That was something I think she needed to hear. I didn’t want to disrespect her, and I think if I’d said, ‘Yeah, I need to find him immediately,’ it would have been saying she wasn’t enough. And she was enough for me.

“Then, after Mum died, there was a moment when I was at her grave at Rookwood, and Nathan had asked me, ‘Where’s your daddy?’ And I felt, not just for me, but for Nathan as well, that he needed to know where his grandfather was.”

A convoluted search followed, across three countries and many years. Finally, miraculously, a dusty old file turned up in an abandoned shed on an Italian wharf. And in it was the missing clue: Carlo Albanese’s employment card with an address, albeit from the 1960s.

It was November 5, 2009, late on a Thursday afternoon. By now, Anthony had become Minister for Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Local Government in Kevin Rudd’s first Prime Ministership. Anthony was about to leave his office for a critical meeting when the phone rang.

It was then-Carnival Cruises CEO Ann Sherry. “I’ve found him,” she said.

“When I finally got that call, it was overwhelming,” he remembers, still grasping for words. “I had to chair a ministerial council meeting at the Hilton in Sydney. I was in my office, and I cried. I had to tell my chief of staff that I needed time to gather [my thoughts]. It took me a while to compose myself. It was an extraordinary moment. Then, once that had happened, I had this absolute sense that I needed to see him.”

Fortuitously, Anthony was due to travel to Italy six weeks later for talks with the European Commissioner for Transport. He contacted a second cousin who worked at the Australian Embassy in Rome, and she helped him craft a letter which they hoped would reach his father.

After all, it had been 46 years. Carlo could have moved. He could have died.

While Anthony was in the air between Australia and Italy, his cousin, Lisa, received a call from a lawyer in the coastal town of Barletta in Puglia. She was, she said, a friend of the Albanese family. A meeting with her was arranged for the following day.

“I wore my best suit,” says Anthony, “and I walked in and put my folder on the table. It had my name on it. We had said in the letter that I was the son of Maryanne Ellery, but not that my name was Albanese. Then I said, ‘I think he’s my father and I just want to meet him.’ And the solicitor said, ‘I will try to make it happen.'”

Anthony with his mother and young son Nathan.

(Image: Instagram)When Carlo Albanese walked into the solicitor’s office the following day, it was, Anthony says, “an incredibly emotional experience for me. I’d had no idea what to expect. He could have said, ‘I don’t know what you’re talking about.’ But the door opened and he just came in and put his arms out.

“It went as well as it could possibly have gone, and he had with him my half-brother and half-sister, Rogero and Francesca, who I didn’t know existed of course. They were incredibly generous. The meeting went for two or three hours. We sat there and we laughed and cried and went through … It was incredibly emotional. It took a lot out of me.”

Anthony had found not only a father, but a whole family on the other side of the world. He returned four months later with Nathan and was treated to an enormous, noisy southern Italian Easter. Carlo died in 2014, but the family remains in touch today.

Anthony returned to Australia in mid-2010 to find his party gripped by turmoil. Its climate change policy, which he had been instrumental in crafting, was being torn asunder by fear and factional rivalries, and his friend Kevin Rudd’s ability to lead a united party was under a cloud.

Anthony is first and foremost a party man, and he did what he could to arrest its self-destructive slide.

WATCH: Why Greta Thunberg thinks climate change is important to young people. Story continues after video.

His role in holding Julia Gillard’s minority government together by hook or by crook (though he’d not supported her tilt at the leadership) was praised by MPs as diverse as Tony Windsor and Bob Katter.

Julia described the political manoeuvrer in Anthony to his biographer, Karen Middleton: “Albo is a persuasive person,” she said. “He’s good at talking people into things. He does his own version of soft cop, hard cop, not needing the second police officer – just doing it all himself.”

Today, Anthony is running for PM with a pitch for national unity. After the divisiveness of the COVID wars and the climate wars, no one doubts that it’s needed. Having pulled together the most motley of crews following Labor’s 2019 federal defeat, and corralled them into a disciplined, campaign-ready team, it is yet to be proven if he has the mettle and the heart for the next part of the job: bringing Australian voters along with them.

As we go to press, Labor’s fortunes are rising, yet so are its critics. He has been accused of being insufficiently bold with his policies; of presenting a “small target”. Questions have been raised about whether Anthony is a sufficiently compelling leader to swing an election to the opposition.

Political correspondent Nick Bryant, who moved to Australia after a long career working for the BBC and has followed campaigns by Barack Obama, Donald Trump and Joe Biden in the States, tells The Weekly:

“There is a charisma deficit there, but I don’t see it as a big problem for Albo. I think, in Australia, charisma isn’t such a valued commodity as it is in the UK or the United States.

“Politics here often rewards the workhorse rather than the show pony, and Albo makes up for a lack of charisma with abundant authenticity.”

Those on the right have also levelled the criticism that Anthony has not yet articulated a convincing or sufficiently detailed plan to pull Australia out of debt. His critics on the left, meanwhile, complain he has sold out the unemployed by refusing to commit to raising JobSeeker.

Labor is, however, promising a suite of policies aimed solidly at female voters: affordable childcare; fairer wages and conditions for people working in aged care; and a guarantee of one registered nurse in every “nursing home”.

They have also promised to implement all the recommendations of Sex Discrimination Commissioner Kate Jenkins’ Respect@Work Report, fund 500 additional community domestic violence workers, and provide 10 days’ family violence leave and 30,000 more emergency and social housing units.

To date, these policies have met with cautious optimism. Aged care advocate Dr Sarah Russell has told The Weekly that the most critical aspect of Labor’s proposal is the promise to make care providers accountable.

“At present,” she says, “when the government gives money to aged care homes, there’s no transparency about the way they spend it. Whether it’s on direct care and meals or executive salaries and sports cars, that’s up to them. Albo’s idea is to tie the government subsidy to direct care, and that’s important.”

She would, however, like Labor’s plan to go further.

“The rorting in the home care sector needs to be addressed as well,” says Sarah.

These issues are also important to Jodie, who is a strategic partnership manager for an industry super fund.

“I’m passionate about ensuring we do everything we can to close the gap for women when it comes to retirement outcomes … The system needs to adapt and acknowledge the issues contributing to the gap, and that starts with gender pay disparity, casualised work, disrupted work patterns and affordable childcare.”

Anthony poses with sex abuse survivor and advocate Grace Tame.

(Image: Instagram)As election day draws nearer, both Anthony and Jodie are aware of the media spotlight shining on them more brightly. Are they ready for it?

“The first time our relationship was outed, it wasn’t by choice,” Anthony says, referring to an early kiss that was captured by paparazzi. “But I think, you know, we do have a relationship and it’s something we’re not shy about.”

“The first time I was out with him, and people wanted photos and to shake his hand, it all felt completely surreal,” Jodie adds. “I remember thinking, ‘Oh, that’s right, this guy is running for PM!’ I know the months ahead will be intense. But my focus will simply be to support each other through it.”

It’s been all the rage in New Zealand and the UK, and it made a great plot line in Love Actually, but is Australia now ready for an unmarried PM?

“Well,” Anthony says with a wry smile, “it wouldn’t be the first time.”

You can read this story and many others in the March issue of The Australian Women’s Weekly – on sale now.

.png?resize=380%2C285)

.jpg?resize=380%2C285)

-copy.jpg?resize=380%2C285)