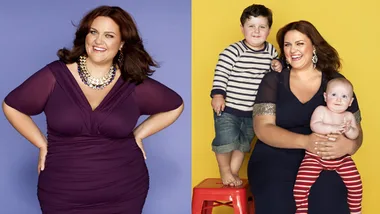

Are you sick of the same old gym routine that delivers the same results? New training trend Crossfit may be just what you need. Woman’s Day’s Karen Birkemoe has taken on the challenge.

THE CHALLENGE

Every so often an exercise program arrives on the scene that everyone is talking about. CrossFit seems to be just that.

I first started hearing about it about a year ago when a couple of girls in the Woman’s Day office started complaining about their sore butts. Soon enough, those butts started shrinking, thanks to CrossFit training.

It’s described as fast, effective and fun, and even Hollywood seems to be jumping on board, with Jessica Biel using it to get in shape for her wedding to Justin Timberlake.

For the next 12 weeks I will embrace the CrossFit way of life to try to shed my unwanted kilos and get CrossFit for the new year. Here is what my challenge involves.

THE LOWDOWN

CrossFit is a high intensity strength and conditioning workout that combines short cardio elements. It was developed by an American named Greg Glassman. One of the main concepts behind CrossFit is constantly varied movements, which means every time you rock up for the work-out of the day you can expect a different workout.

This not only keeps your muscles guessing (and reacting) but also means you don’t suffer from boredom, which is a common complaint from gym workouts.

CrossFit attracts participants from all walks of life with varying ability and has won world-wide success. Each year, CrossFit Games are held in California, where the fittest men and women from around the world battle it out over three to four days of competition to be crowned the fittest on earth.

“CrossFit is a core-strength and conditioning program designed to work your body as it was intended – as a complete unit,” says Christian d’Astoli, Co-founder of CrossFit Athletic in Brookvale, Sydney.

“The workouts consist of large, functional and multi-joint movements such as pushing, pulling, squatting, lifting, throwing and jumping, which are performed at high intensity. “Our goal is to create the quintessential athlete – equal part gymnast, weightlifter, sprinter, rower and 800m runner.”

What a work-out involves

A CrossFit work-out focuses on 10 key fitness domains including:

Cardiovascular endurance

Stamina

Strength

Flexibility

Power

Speed

Agility

Balance

Co-ordination

Accuracy

THE LINGO

Like any new work out regime, CrossFit has its own unique set up. Here is what you will need to know.

WOD: Stands for Workout of the Day and that’s what it is because it literally changes every day, so expect the unexpected.

AMRAP: Stands for As Many Reps As Possible. Given a specific exercise or exercise sequence, you are expected to go as fast as you can while following correct form, and perform as many repeats as you can in a given time.

TABATA: High-intensity interval training. For example, 20 seconds skipping followed by 10 seconds of rest x however may rounds.

See www.crossfitathletic.com.au for more.

Newsletter conversion description. Get the latest in your inbox.

.png?resize=380%2C285)

.jpg?resize=380%2C285)