I’m not sure how most fathers react when they are told that their newborn baby has Down syndrome, but if I am anything to go by it involves crying for a week.

Six hours after the birth of our youngest daughter Emma we were told that she most likely had Down syndrome. The news wasn’t completely out of the blue — an ultrasound had revealed a slightly thicker nuchal fold, but there were no other indicators, and we were told the chances were about one in 200.

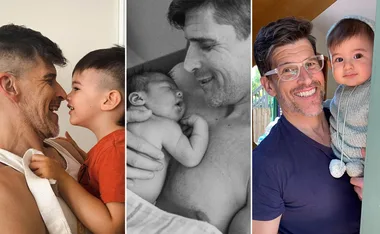

In pictures: Meet my beautiful child with Down syndrome

But when I had first held Emma in my arms I looked at her and saw only a wonderful (very small) girl. And so it was a shock to be told that she was being moved to the neonatal ICU ward and they were to run a series of tests — both physical and genetic.

And so I cried for a week.

Why did I cry? If I’m honest, mostly it was for myself. Emma was sweetly sleeping in the humidicrib unaware that there were any issues that should stop her from sleeping sweetly. She had no health problems — many newborns with DS do have issues with their heart and bowels, she didn’t. Other than needing help to keep warm due to her small size, she was happy and content.

But I was a mess.

I cried out of fear — fear that I wouldn’t be able to cope, and shamefully I worried I would forever look at her with a sense of disappointment. Like many fears it was based on a prejudice fostered by ignorance.

I had no idea what DS was, so I assumed the worst — that I’d never communicate with her, that she would spend her days inert and dull, that she could never learn, that she would not have her own desires and ambitions. These mistaken beliefs meant I stopped dreaming for my daughter.

In that first week I closed the book on a raft of possibilities for Emma, because based on my ignorance of Down syndrome I thought of Emma as a plural and not a singular.

My ignorance led me to assume not only were all my misconceptions accurate, but that all people with DS were the same — as though the addition of a third copy of chromosome 21 somehow subtracted the person’s individuality. Thus assumptions that “they can’t do” meant “Emma can’t do”.

Well I was wrong. Massively so.

Emma is an individual with her own personality and desire for independence. Far from being inert and dull, she is forever dashing here and there, ready to bounce for hours (hours!) on the trampoline, relax reading a book or helping bake biscuits, and is always determined to do things by herself. She took about 10 seconds to discover how to take photographs with my iphone. And when she laughs you cannot but laugh with her.

This February Emma began attending kindergarten at the local primary school. In this sense she is now a plural — she, like everyone else is expected to listen and obey the teacher. But like everyone else is an individual in the class.

‘You are my hero’: A mum’s letter to her baby with Down syndrome

Of course it is not all easy. But what child is? No one becomes a parent because they want to have a lot more spare time.

But far from my looking at her with disappointment, my heart leaps when she runs to me from her classroom at the end of each day.

I was right the first time I saw her — she is wonderful.

And when I hold her hand I am the proud one, as I dream of the things she might achieve.

Newsletter conversion description. Get the latest in your inbox.

.jpg?resize=380%2C285)