Growing up in Melbourne in the 1950s, Eve Ash had a happy childhood in a close family. Her Polish parents, Feliks and Martha, were Holocaust survivors who had lost dozens of loved ones, but they kept their past traumas to themselves, adamant their pain would not cast a pall over another generation.

“We were very aware that there were other Jewish families that were very twisted and mentally anguished,” says Eve. “They had thrown at them, ‘You don’t know what we went through.’ We never had any of that.”

Feliks, who built up a successful sportswear business, could be socially reticent, but Martha was a bon vivant – a beautiful, flirtatious artist who used to lie about her age and throw elaborate themed parties at their home in Murrumbeena. She was a devoted mother to Eve and her older sister, Helen, but also an enigma.

“I don’t know why,” says Eve, 64, a psychologist and filmmaker, “but I always felt there was a secret.”

At first, Eve thought she might be adopted – “I felt like an Australian implant in this European family” – but her feelings could easily be explained away: six years younger than Helen, Eve was the only one born in Australia, in 1951, two years after her family had migrated. Martha also had the hospital bracelet Eve had worn as a newborn.

Yet Eve’s suspicions persisted, especially after she discovered her parents’ wartime secrets when she was 14. Feliks had been forced to work in a concentration camp, processing dead bodies, while Martha spent the war on the run, pretending not to be Jewish. They had both been married before, their much-loved partners killed by the Nazis.

When Feliks died in 1985, Eve wondered again whether she and Helen had different fathers. Before Martha died in 1996, she even asked her mother point-blank if she had had affairs, but Martha dismissed the question as “ridiculous”.

Eve raised her two children, ran her film production company and tried to let it go – until a stranger sent her an email in 2008, claiming to be her half-sister.

Micheline Lee was Eve’s mirror image and the daughter of Ronald “Dixie” Lee, a fondly remembered family friend who had been a regular at her parents’ parties. The women sent off cheek swabs to a DNA testing company and the results showed it was 99.99 per cent likely they were half-sisters.

The mystery began to unfold. As Eve set off to confront her birth father eight years ago, she knew she had to capture it on camera, so she began making Family Secrets, documenting her own journey of discovery as well as her mother’s “psychological history” of atrocity and survival.

Eve and Helen have travelled to Poland to piece together Martha’s life story, creating a picture of the complex woman she was. Along the way, Eve has found a new compassion for Martha – and forged an amazing bond with the man with whom her mother had an affair.

Today, we meet in Eve’s home in inner Melbourne, an architect-designed warehouse conversion filled with modern art.

“You couldn’t make up this story,” says Eve, as she chronicles a tale of secrets and lies that veers off on curious tangents and involves coincidences too far-fetched for fiction.

Eve, it turns out, had suspected Dixie for years. He had done some surveying for her in the 1980s and Eve was so struck by their physical similarities that she asked when he had met her mother. Keen to protect Martha, Dixie lied and said it was after Eve was born.

In the early 2000s, one of Dixie’s sons contacted Eve after hearing her talking on radio about her new books, ironically titled Rewrite Your Life! and Rewrite Your Relationships!

Eve didn’t know the man, but he remembered his parents being friends with hers, and Eve shared her paternity suspicions with him. Those suspicions eventually found their way to Dixie’s daughter.

Then there was the Melbourne street directory. Martha had told Eve that Dixie, a land surveyor, had named streets after them, and Eve thought that meant all four members of her family – but she only found “Eve” and “Martha” in the same estate. “That,” she says, “was one of the biggest clues that he was my father.”

When Eve confronted Dixie in 2008, it was under the guise of interviewing him for a film on Martha’s life. Sitting in a shopping centre in Werribee, Eve felt faint as she told him she knew he was her father. Dixie was relieved that the secret was out; he said he’d followed her career online and thought of her every year on her birthday.

“I found that really emotional,” Eve recalls, “but I didn’t immediately feel love. I hadn’t discovered a long-lost loving parent. I’d discovered … my mum’s lover.”

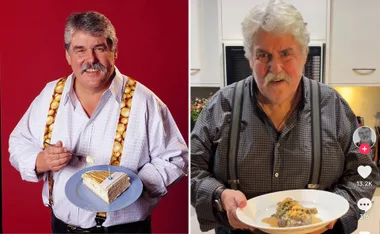

A picture of rude 91-year-old health, Dixie arrives at Eve’s house after we’ve been chatting for an hour or so. Still working as a land surveyor, he is immaculately groomed, with a beard that lends him a startling resemblance to KFC’s Colonel Sanders. His mobile goes off and the ring tone is the first distinctive bars of Bad to the Bone.

This is a man clearly unwilling to go gentle into that good night. He served as a marine in World War II, had five wives and two affairs (resulting in 10 children), played A-grade chess, built a yacht and sailed the Pacific – and he has no intention of ever retiring.

Born in Burnie, Tasmania, Dixie was a married 25-year-old father of two when he met Martha, 33, a new migrant with one child, on the North Road bus in mid-1949. The connection was electric, even if

they had to rely on Dixie’s schoolboy French to communicate.

“She had a delightful accent,” Dixie recalls. “We were together for 20 minutes or so and we’d look forward to each time. I took to really sprucing myself up.”

Before long, Martha and Dixie were having secret trysts three times a week. Their spouses had no idea.

In early 1951, when Martha told Dixie she was pregnant, he was pleased. When Eve was born, he took flowers to the hospital within hours of her birth. Guilt never came into it, for either of them.

“It was just full bore – we were oblivious to everything else,” says Dixie. “We seemed made for each other.”

Eve can understand the attraction. “Maybe there was something about Dixie that was reminiscent of her lost love,” she muses. “Maybe a part of her had died in the war and Dixie ignited in her passion again.”

As for Martha and Feliks, theirs was a safe relationship, if perhaps not a sexually exciting one; Eve certainly doesn’t remember any threat of a break-up. Bonded by their Holocaust experiences, “they were family”, she says.

The two couples socialised – and Dixie and his wife even looked after the Ash girls when Feliks and Martha went overseas on business – but no one knew of the affair. In the mid-1950s, Martha became pregnant again, but couldn’t pretend Feliks was the father this time. Dixie still remembers taking her to an abortionist in Toorak. “It had to be done,” he says. “Her whole world would have fallen apart.”

The affair lasted more than 15 years, spanning Dixie’s first two marriages, but there was never any talk of running away together. “We just pleasured each other over the years,” he says. “She had no thought of leaving her life and neither did I.”

Dixie left Melbourne, though, to move overseas in the early ’70s. He married his third wife (the niece of his second) and lived with her and another woman in a ménage à trois for years – until the two women eventually left him for each other. He returned to Australia in the 1980s and has been with his current wife for more than 35 years.

With that kind of history, it would be reasonable to assume his children might carry resentment, but Eve says she has none of that baggage. Dixie has even shown Eve the exact spot of her conception, behind the bathing boxes on Brighton Beach. “He did an X on the sand,” she says wryly. “Being into geography and mapping, we’ve got a bit more accuracy than most.”

Dixie went along recently when Eve filmed scenes for her documentary, recreating the bus encounters 67 years ago with actors in period costume.

Together, we watch the scenes on Eve’s computer: the moment Dixie and Martha first meet; the pair sharing a kiss behind a newspaper; the young mum in a pretty polka-dot dress. When the screen fades to black, Dixie is silent for a moment, seemingly overcome by emotion or nostalgia or both.

The postscript to this story is the extraordinary father-daughter friendship that has grown between Eve and Dixie – to the point where they now speak on the phone every second day. They are both atheists and human rights supporters incensed by injustice.

“I think Mum would love to know that we have bonded,” says Eve. “She would also be grateful she doesn’t have to take any crap. Her subterfuge had gone on too long and I’m not sure she could have handled the exposure.”

Not that Eve is judging her. After all the horror her mother had endured, Eve can’t condemn her for seizing any opportunity for happiness.

“Everything was grabbed out from under her,” says Eve. “Maybe those war experiences bring out in you [the belief that] you have to live for the moment. Anything can happen next.”

This story originally appeared in the April issue of The Australian Women’s Weekly.